A collection of conversations with a diverse range of local and regional creatives

Library Conversations for SGABF2020

We examined the systems that support art book making and independent art book publishing in Singapore and the region.

A Closer Look for SGABF2019

We gathered perspectives on our zine and art book culture, and discuss the possibilities of self-publishing today.

21 Creatives for SGABF2018

We sat down with 21 creatives of various disciplines to learn about their practice and asked each of them to fill up a blank page in a notebook.

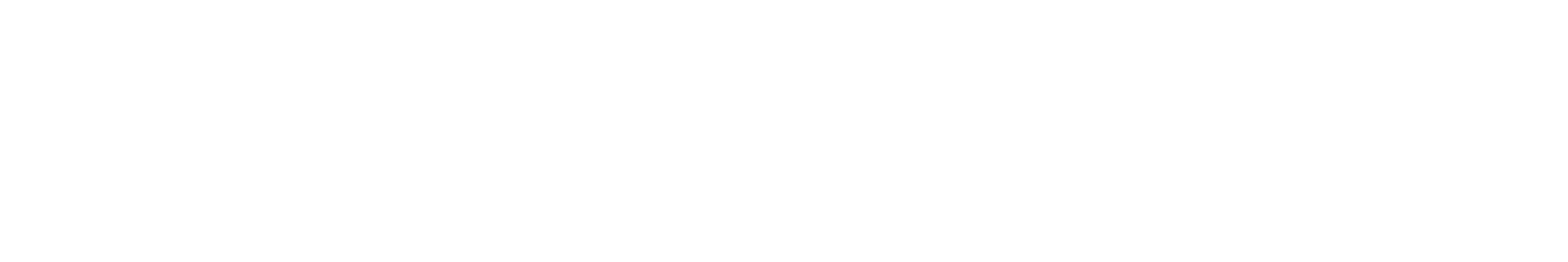

Photo Credit: THEBOOKSHOW

SONG NIAN (SN): Pictures of My Life was immediately interesting to me because it doesn't really fall into the typical categories. It doesn't fit with how people typically think about photobooks or coffee table books. Pictures feels like an encapsulation of several different materials which the artist has put together as a book. It mainly contains paintings and photographs – some of the photographs are taken by the artist himself, others are earlier photos of Ueda's childhood taken by his father. The artist also incorporates into his book these texts in Japanese, along with their English translation.

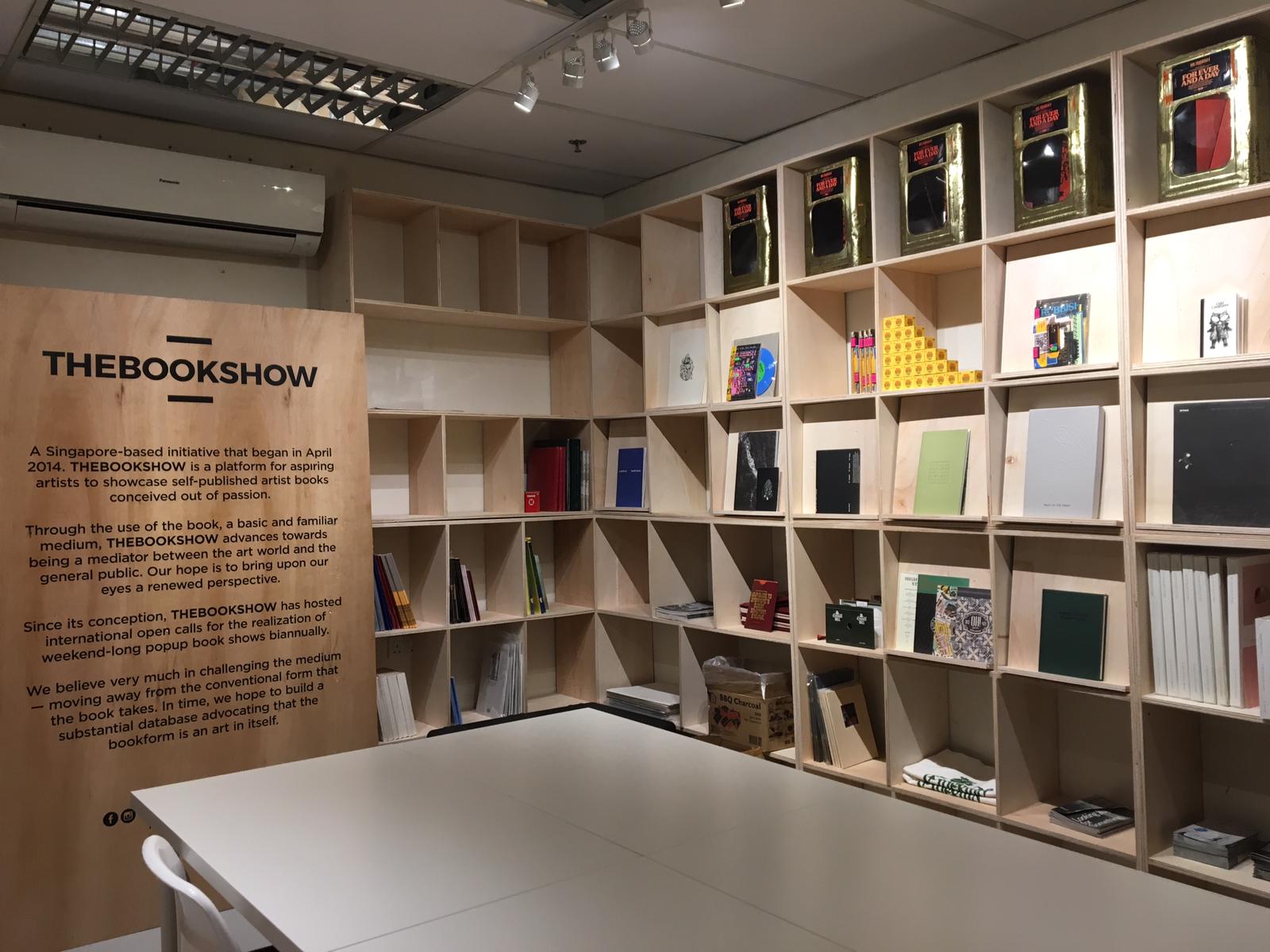

Pictures of

My Life,

Junpei Ueda. Image Credit: Junpei Ueda

Pictures of

My Life,

Junpei Ueda. Image Credit: Junpei Ueda

SN: Beginning with the cover of the book, you are immediately confronted not with a photograph but a painting – a portrait of the artist's younger self. What is revealed to you through the book is the artist's memories of his childhood, followed by the passing of his mother and then the passing of his father. After his mother had committed suicide, his father, not being able to deal with his grief, followed suit. What you can see is the artist trying to make sense of the situation. Towards the end of the book, there is a photograph of Ueda, his wife, and their two daughters. I had spoken to the artist particularly about this, and he said that this was his way of putting forth a reassurance both into the world and to his parents who had passed.

SN: Pictures of my Life feels less like a book and more like an artefact that is put together with different materials which reveal different parts of his life. While going through the book from front to back, it doesn't feel static or linear; there are pauses in the book that allows the reader to take a step back or retreat with the artist into where his mind is, and to listen to what he wants to tell us via the text. That is why I think that the book has such a strong emotional power, which is why I wanted to share this work.

LEANNA TEOH (LT): I think the most important thing about the book, both as an art medium and as an art object, is its portability and longevity. Having a book is like having an exhibition that lives beyond the space; you can view it at any time and any place, with a unique intimacy. Unlike an exhibition, you won't be interrupted by other people viewing the work at the same time. The book is a very intimate object.

I don't really know what, for me, is the difference between the book as a medium and as an object. What we are trying to advocate is that the book is a mode of expression, and that it is different from, for example painting and photography, because you can propose a narrative within the medium.

OBJECT LESSONS SPACE (C): Hi Song Nian and Leanna, thanks for having us with you in your studio today. Let’s begin with talking about your first selection, Picture of My Life. This is a self-published book, which is handmade by artist Junpei Ueda through a workshop titled Photobook as Object. It contains photographs, illustrations, and folded pieces of written correspondence with his parents. Do you see a particular physicality that comes with books and bookmaking?

SONG NIAN (SN): Pictures of My Life was immediately interesting to me because it doesn't really fall into the typical categories. It doesn't fit with how people typically think about photobooks or coffee table books. Pictures feels like an encapsulation of several different materials which the artist has put together as a book. It mainly contains paintings and photographs – some of the photographs are taken by the artist himself, others are earlier photos of Ueda's childhood taken by his father. The artist also incorporates into his book these texts in Japanese, along with their English translation.

SN: Beginning with the cover of the book, you are immediately confronted not with a photograph but a painting – a portrait of the artist's younger self. What is revealed to you through the book is the artist's memories of his childhood, followed by the passing of his mother and then the passing of his father. After his mother had committed suicide, his father, not being able to deal with his grief, followed suit. What you can see is the artist trying to make sense of the situation. Towards the end of the book, there is a photograph of Ueda, his wife, and their two daughters. I had spoken to the artist particularly about this, and he said that this was his way of putting forth a reassurance both into the world and to his parents who had passed.

SN: Pictures of my Life feels less like a book and more like an artefact that is put together with different materials which reveal different parts of his life. While going through the book from front to back, it doesn't feel static or linear; there are pauses in the book that allows the reader to take a step back or retreat with the artist into where his mind is, and to listen to what he wants to tell us via the text. That is why I think that the book has such a strong emotional power, which is why I wanted to share this work.

OLS: What do you see as unique to the book both as a medium for art, and as an art object?

LEANNA TEOH (LT): I think the most important thing about the book, both as an art medium and as an art object, is its portability and longevity. Having a book is like having an exhibition that lives beyond the space; you can view it at any time and any place, with a unique intimacy. Unlike an exhibition, you won't be interrupted by other people viewing the work at the same time. The book is a very intimate object.

I don't really know what, for me, is the difference between the book as a medium and as an object. What we are trying to advocate is that the book is a mode of expression, and that it is different from, for example painting and photography, because you can propose a narrative within the medium.

SN: When we look out for photographic works, we look out

for works that somehow—I don't want to say they only make sense as a book, but

in particular when it is being produced as a book or publication—demonstrate

that the concept or message of the work is able to extend beyond merely working

as images; be that in a frame, a slideshow or a projection.

Back to the physicality of the book, the way a book is crafted matters. All these elements—from the design, the cover, the layout, and even the end pages, the binding and inserts—lend layers to the way we experience an artwork in the book medium.

SN: Gaining acceptance for photography in the art world has always been an uphill task. Fortunately, in the last ten to fifteen years, we have seen an improvement in the way photography is being perceived in the art world. When photography first started to be mass produced, it was used for a very specific purpose in editorial work, journalism and newspapers – in terms of disseminating messages. That is what people saw to be the main role of photography. I think we see photography coming up slowly with this medium being explored within various art disciplines.

The relationship between photography and print is related to that of performance art and video, which also have always been very close and very strongly bound together. Performance work needs to firstly exist by itself, but for it to continue to exist, or for people to know that it has once existed, it then depends on the video work that was done during the live performance.

There is another whole conversation that can be had about the movement from painting to photography. There has always been a painting-versus-photography dialogue going on, of, for example, which one is better. Within the art world, photography gained traction at a slower pace, possibly because it was produced in editions. As the number of editions become smaller, we start to see it becoming more accepted by collectors. People also become more willing to buy photography work as fine art. Print will always be important to photography, even as we start to see photography work in other presentation formats. I'm quite hopeful about the acceptance of photography in the art world. It's changing, just slowly.

SN: I think we are coming up with ways to firstly enable people to produce content, in terms of the programmes, exhibitions, open calls and workshops. We are also finding ways to bridge the distance between those making the books, and everyday people, who also otherwise access photography on a daily basis.

This project is still very young - we started in 2014. Prior to THEBOOKSHOW working more actively, we did observe some efforts by other groups or initiatives pertaining to the photobook but there is no prolonged effort in looking at the photobook medium. In terms of providing opportunities for people who create, we have also started several initiatives such as open calls, which lead to exhibitions, which lead to prizes and awards. In terms of showcasing books, we also actively promote at international art book fairs and work on partnerships with collaborators from overseas to disseminate or to exhibit. A healthy exchange would be one where we show books from overseas, then have our books shown there too.

There are a lot of things we're doing at the same time, all with the hope of growing the appreciation of the photobook as a medium of art.

![]()

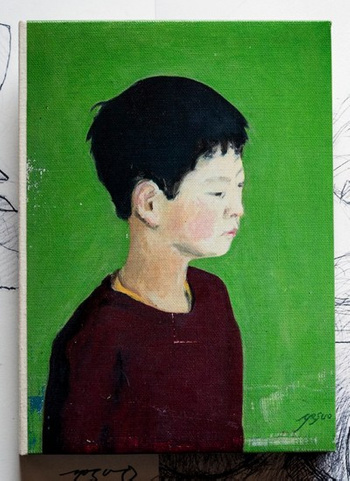

A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Institute of Critical Zoologists

SN: A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World was initially self-published. Subsequently, Robert Zhao submitted it to the Steidl Book Award: Asia Open Call, which was when it was selected to be one of the eight books to be published by Gerhard Steidl. The edition that Steidl published is slightly different from his original self-published version. If you look towards the back of the book, there are many of these smaller booklets that are included in the box, which were not in the first edition. I selected this book because it has particularly received quite a lot of attention internationally; I think the main reason for that is because many people are already aware of Robert's work and his practice. I feel that this is the pride and joy of Singapore's self-publishing efforts.

Back to the physicality of the book, the way a book is crafted matters. All these elements—from the design, the cover, the layout, and even the end pages, the binding and inserts—lend layers to the way we experience an artwork in the book medium.

OLS: What do you see as the importance of print to photography? Do you see photography as adjacent to or contained within art?

SN: Gaining acceptance for photography in the art world has always been an uphill task. Fortunately, in the last ten to fifteen years, we have seen an improvement in the way photography is being perceived in the art world. When photography first started to be mass produced, it was used for a very specific purpose in editorial work, journalism and newspapers – in terms of disseminating messages. That is what people saw to be the main role of photography. I think we see photography coming up slowly with this medium being explored within various art disciplines.

The relationship between photography and print is related to that of performance art and video, which also have always been very close and very strongly bound together. Performance work needs to firstly exist by itself, but for it to continue to exist, or for people to know that it has once existed, it then depends on the video work that was done during the live performance.

There is another whole conversation that can be had about the movement from painting to photography. There has always been a painting-versus-photography dialogue going on, of, for example, which one is better. Within the art world, photography gained traction at a slower pace, possibly because it was produced in editions. As the number of editions become smaller, we start to see it becoming more accepted by collectors. People also become more willing to buy photography work as fine art. Print will always be important to photography, even as we start to see photography work in other presentation formats. I'm quite hopeful about the acceptance of photography in the art world. It's changing, just slowly.

OLS: How do you see THEBOOKSHOW’s role then, as a mediator or bridge of sorts?

SN: I think we are coming up with ways to firstly enable people to produce content, in terms of the programmes, exhibitions, open calls and workshops. We are also finding ways to bridge the distance between those making the books, and everyday people, who also otherwise access photography on a daily basis.

This project is still very young - we started in 2014. Prior to THEBOOKSHOW working more actively, we did observe some efforts by other groups or initiatives pertaining to the photobook but there is no prolonged effort in looking at the photobook medium. In terms of providing opportunities for people who create, we have also started several initiatives such as open calls, which lead to exhibitions, which lead to prizes and awards. In terms of showcasing books, we also actively promote at international art book fairs and work on partnerships with collaborators from overseas to disseminate or to exhibit. A healthy exchange would be one where we show books from overseas, then have our books shown there too.

There are a lot of things we're doing at the same time, all with the hope of growing the appreciation of the photobook as a medium of art.

OLS: One such award was the Steidl Book Award, in which THEBOOKSHOW had helped to put together the finalist showcase. One of the winners was Robert Zhao’s A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, which you have also chosen as part of your selection. Tell us more about that.

A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Institute of Critical Zoologists

SN: A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World was initially self-published. Subsequently, Robert Zhao submitted it to the Steidl Book Award: Asia Open Call, which was when it was selected to be one of the eight books to be published by Gerhard Steidl. The edition that Steidl published is slightly different from his original self-published version. If you look towards the back of the book, there are many of these smaller booklets that are included in the box, which were not in the first edition. I selected this book because it has particularly received quite a lot of attention internationally; I think the main reason for that is because many people are already aware of Robert's work and his practice. I feel that this is the pride and joy of Singapore's self-publishing efforts.

What we see with A Guide is not a typical

book with bindings; it makes a lot of sense for the book to be presented in a

plate format. This is also in line with his practice, as he had also come up

with the Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ). We see plates used in

scientific journals. That's the kind of terminology and format that they use in

the scientific process. Robert uses that kind of reference heavily such that

his books have the aesthetics of research reports. I think that's why people

find this book to be a breath of fresh air, compared to the usual art books and

photobooks one usually encounters.

LT: I think the biggest hurdle is cost, especially in Singapore where printing is a lot more expensive than in other places. For example, the cost of maintaining the printing machines themselves is already high, because we must get technicians to come in from overseas, which drives up the base price. Other than the cost of printing, it really depends on your network to get the book out into the open. Most of the time self-publishing artists market their books either through competitions and open calls like ours, or they show their work in fairs. These are the venues through which readers find out about artbooks, other than at bookstores. To participate in a fair also generates additional cost. The cost of printing and marketing are the hardest things; it's everything to do with cost.

SN: That aside, we felt that the network and infrastructure for helping people with self-publishing was almost non-existent in Singapore. That's what we want to do - we see ourselves as a platform. We started out with that idea of wanting to provide more opportunities for people. As the years went by, we realised that apart from the cost, it's also about getting access to the right kind of designers and printers. Apart from budget, and access to the right kind of people and network, we found that storage and dissemination also play a key part. You can self-publish a hundred copies, three hundred copies, a thousand copies - but how are you going to move the books? I think this also proved to be quite a challenge when it comes to self-publishing.

Of course, there are things like kickstarter campaigns, but those are also slowly getting saturated and losing their novelty. There have been some successful cases, for example Dark Cities by Shyue Woon, which was also part of our project First Draft. He won a $5000 sponsorship by Allegro, a local printing company, through First Draft. In addition to that, he also launched a kickstarter campaign, which I felt was rather effective. Dark Cities is now onto a second edition, which is again aided by a kickstarter campaign.

If we look away from the perspectives of people creating the work, there are also challenges from a publisher’s point of view. That is something that THEBOOKSHOW is experimenting with. What we find to be a challenge is having access to a sufficient amount of works to select from and to publish. In alignment with the kind of publishing work that we are slowly planning to do, we have to also put in motion avenues, channels, or initiatives to encourage people to make more works. The fact is that if there's nobody making, there's no one for us to publish. Since we focus on Singaporean artists, we have a smaller pool to work with. It's then even more important for us to get the momentum going. Only if the selection pool gets bigger, then we are able to really sieve out the works that are of a higher quality.

One such work would be The Mountain Survey by Marvin Tang, which he published in a very small run in 2016 as part of a show of the same name. Marvin's practice relies heavily on research. For this project, he started with looking at the Xiao Guilin quarry landscape. He then realised that granite, as a resource, played a pivotal role in the narrative of nation-building. He found out that Xiao Guilin wasn't the only one, that there were other quarries and that Singapore sits on granite. That explains why it was also one of the more common resources that was being used in building.

What I was captivated by was the mix of research materials that he found, which he used to really inform different parts of the book. We see different types of images. Some were very formal representations of the landscapes in these decommissioned granite quarries. Others show people just staring at the landscape. I found that to very impressive – Marvin’s observation didn’t end with simply looking at whatever was in front of him. He saw what really makes up the landscape. He realised that people were spending such a considerable amount of time at these places, staring off into the distance at these fake mountains, with their backs to the world. There were all these different kinds of traces people left around the vicinity. It's not just a monotonous presentation of all the different granite quarries, but also showed the way people behave, respond and react to these landscapes, that are now being positioned as a place solely for recreational enjoyment, which is held in stark comparison to all the exempt historical purposes that these granite quarries used to serve.

OLS: This is originally a self-published book. In many of your open calls, you specifically ask for self-published or unpublished work. What is the importance of and difficulties in self-publishing?

LT: I think the biggest hurdle is cost, especially in Singapore where printing is a lot more expensive than in other places. For example, the cost of maintaining the printing machines themselves is already high, because we must get technicians to come in from overseas, which drives up the base price. Other than the cost of printing, it really depends on your network to get the book out into the open. Most of the time self-publishing artists market their books either through competitions and open calls like ours, or they show their work in fairs. These are the venues through which readers find out about artbooks, other than at bookstores. To participate in a fair also generates additional cost. The cost of printing and marketing are the hardest things; it's everything to do with cost.

SN: That aside, we felt that the network and infrastructure for helping people with self-publishing was almost non-existent in Singapore. That's what we want to do - we see ourselves as a platform. We started out with that idea of wanting to provide more opportunities for people. As the years went by, we realised that apart from the cost, it's also about getting access to the right kind of designers and printers. Apart from budget, and access to the right kind of people and network, we found that storage and dissemination also play a key part. You can self-publish a hundred copies, three hundred copies, a thousand copies - but how are you going to move the books? I think this also proved to be quite a challenge when it comes to self-publishing.

Of course, there are things like kickstarter campaigns, but those are also slowly getting saturated and losing their novelty. There have been some successful cases, for example Dark Cities by Shyue Woon, which was also part of our project First Draft. He won a $5000 sponsorship by Allegro, a local printing company, through First Draft. In addition to that, he also launched a kickstarter campaign, which I felt was rather effective. Dark Cities is now onto a second edition, which is again aided by a kickstarter campaign.

If we look away from the perspectives of people creating the work, there are also challenges from a publisher’s point of view. That is something that THEBOOKSHOW is experimenting with. What we find to be a challenge is having access to a sufficient amount of works to select from and to publish. In alignment with the kind of publishing work that we are slowly planning to do, we have to also put in motion avenues, channels, or initiatives to encourage people to make more works. The fact is that if there's nobody making, there's no one for us to publish. Since we focus on Singaporean artists, we have a smaller pool to work with. It's then even more important for us to get the momentum going. Only if the selection pool gets bigger, then we are able to really sieve out the works that are of a higher quality.

One such work would be The Mountain Survey by Marvin Tang, which he published in a very small run in 2016 as part of a show of the same name. Marvin's practice relies heavily on research. For this project, he started with looking at the Xiao Guilin quarry landscape. He then realised that granite, as a resource, played a pivotal role in the narrative of nation-building. He found out that Xiao Guilin wasn't the only one, that there were other quarries and that Singapore sits on granite. That explains why it was also one of the more common resources that was being used in building.

What I was captivated by was the mix of research materials that he found, which he used to really inform different parts of the book. We see different types of images. Some were very formal representations of the landscapes in these decommissioned granite quarries. Others show people just staring at the landscape. I found that to very impressive – Marvin’s observation didn’t end with simply looking at whatever was in front of him. He saw what really makes up the landscape. He realised that people were spending such a considerable amount of time at these places, staring off into the distance at these fake mountains, with their backs to the world. There were all these different kinds of traces people left around the vicinity. It's not just a monotonous presentation of all the different granite quarries, but also showed the way people behave, respond and react to these landscapes, that are now being positioned as a place solely for recreational enjoyment, which is held in stark comparison to all the exempt historical purposes that these granite quarries used to serve.

Mountain Survey, Marvin Tang. Photo Credit: Marvin Tang

OLS: The production process that goes into a work seems to be very important to you. Your workshop project Dirty Laundry especially focuses on this process of bookmaking, and the notion of what makes something "suitable" or "good", or "ready" to be published.

LT: Dirty Laundry was made to involve people who were not "in the know" of the art world. The workshop starts with the topic of how to assemble a book and the more technical aspects of bookmaking. During the process, we also try to subtly instil ideas of what a book can be, and talk about how to view and understand a book. All our programmes are geared towards educating the public about the book and how it can be a form of art.

SN: Dirty Laundry was set up as a workshop which involves contribution by and from the participants. In this edition, we capped it at twenty participants. Each are asked to bring between thirty to forty images, printed in whatever kind of format they prefer, as long as it's smaller than an A4 size. Everyone will come in with images that they deem to be "bad", and we start the discussion from there. In this day and age, with the way we use photography in social media, we can't run away from the fact that people always want to present the best side of things; they always try to show how much they're enjoying their lives and how good they have it. I feel that there are a lot of images that have fallen through the cracks. I also think the concept of a "bad" photograph is quite problematic. What we are after in Dirty Laundry is the intention of the image, of what it is really meant to convey or say. That's why we decided to invite people to bring in what they think are "bad" photographs.

At the start of the workshop everyone will lay their images on the table, and they will talk about their images and why they think it is a "bad” photograph. Through that sharing, participants will start to realise that everyone's interpretation of "bad" is varies. Looking at each other's photos, sometimes they will find that the photos is only "bad" from that person's own perspective.

After they take the time to look at and hear about the images, participants are then given time to put together a zine or a book with the images that belong to everybody. It's a free-for-all kind of approach, where you are allowed to use not just your own photos but also other people's photographs.

The name Dirty Laundry comes about because everyone brings in their bad photos to the table and share about it openly. Though we definitely hope for some profits from this project, we started it not specifically to earn money, but instead as a project of content-production or creation. It is a way for us to collect images of the vernacular, which comes from participants of different groups, ages and backgrounds. The images that they provide are all taken by themselves. We found that to be a good way of building up an archive of images of the everyday, not taken by artists or photographers, but coming in from different walks of life. Dirty Laundry has slowly evolved to be something that's very central to what THEBOOKSHOW does and what we believe in.

THEBOOKSHOW is an avenue for artists to showcase self-published art books in exhibitions and art festivals. It connects the arts community through showcases and activities centering the art book and its presentation, moving away from the conventional form and bringing upon renewed perspectives of the medium.

© Singapore Art Book Fair 2025. All rights reserved.

For further enquiries, please contact us at info@singaporeartbookfair.org.

Singapore Art Book Fair is organised by

![]()

For further enquiries, please contact us at info@singaporeartbookfair.org.

Singapore Art Book Fair is organised by