A collection of conversations with a diverse range of local and regional creatives

Library Conversations for SGABF2020

We examined the systems that support art book making and independent art book publishing in Singapore and the region.

A Closer Look for SGABF2019

We gathered perspectives on our zine and art book culture, and discuss the possibilities of self-publishing today.

21 Creatives for SGABF2018

We sat down with 21 creatives of various disciplines to learn about their practice and asked each of them to fill up a blank page in a notebook.

Display Distribute

OBJECT LESSONS SPACE (OLS): Hi Display Distribute! Let’s start with the first question stemming from your selection of Kate Rich's Feral Trade project. This project is an exploration of the "carrying power" that people possess as travellers and moving bodies and the bodily involvement in transporting objects. For her, the organic quality of what is transported is part of the appeal, and she had claimed that "it would be much harder to ask people to carry something inert, like rocks or books".

How do you see the relationship between books, specifically art publications, and its movement across space both in its production and distribution process? Do you see an aesthetic quality about this network of distribution that you have set up via LIGHT LOGISTICS, or is this a matter of resistance, organization, and possible ethics?

DISPLAY DISTRIBUTE (DD): The Feral Trade project is a crucial point of reference for LIGHT LOGISTICS—so funny that you've happened upon this particular reference from Kate! Would be nice in light of that if there was an opportunity to see how she would reflect on our project. But in this context of being transported as illicitly carried goods (the question you have probably heard before at check-in: ‘Has anyone asked you to carry any extra items on board with you today?’), I’m not sure if I agree with the fact that the question of organicity contributes to appeal. The paranoia of a glass bottle of olive oil possibly breaking in my suitcase sounds quite unappealing, actually. But whether the carried items are books or cheese, the fact of being packed into checked luggage or shoved into a backpack actually points not to the qualities of the object itself, but to all the movements which flow with and around the cargo, and this is where the question of organic is much more interesting. Are capitalism, outsourcing, baggage handling, industrial food growth, our own bodies travelling thousands of kilometres for work or pleasure organic? The way we relate to objects is inherently mediated, but as the coronavirus pandemic has put into such stark clarity, things and certain ways of doing we previously took to be natural can suddenly come grinding to a halt, and human activity on earth can engineer ‘novel’ forms of organic transmission.

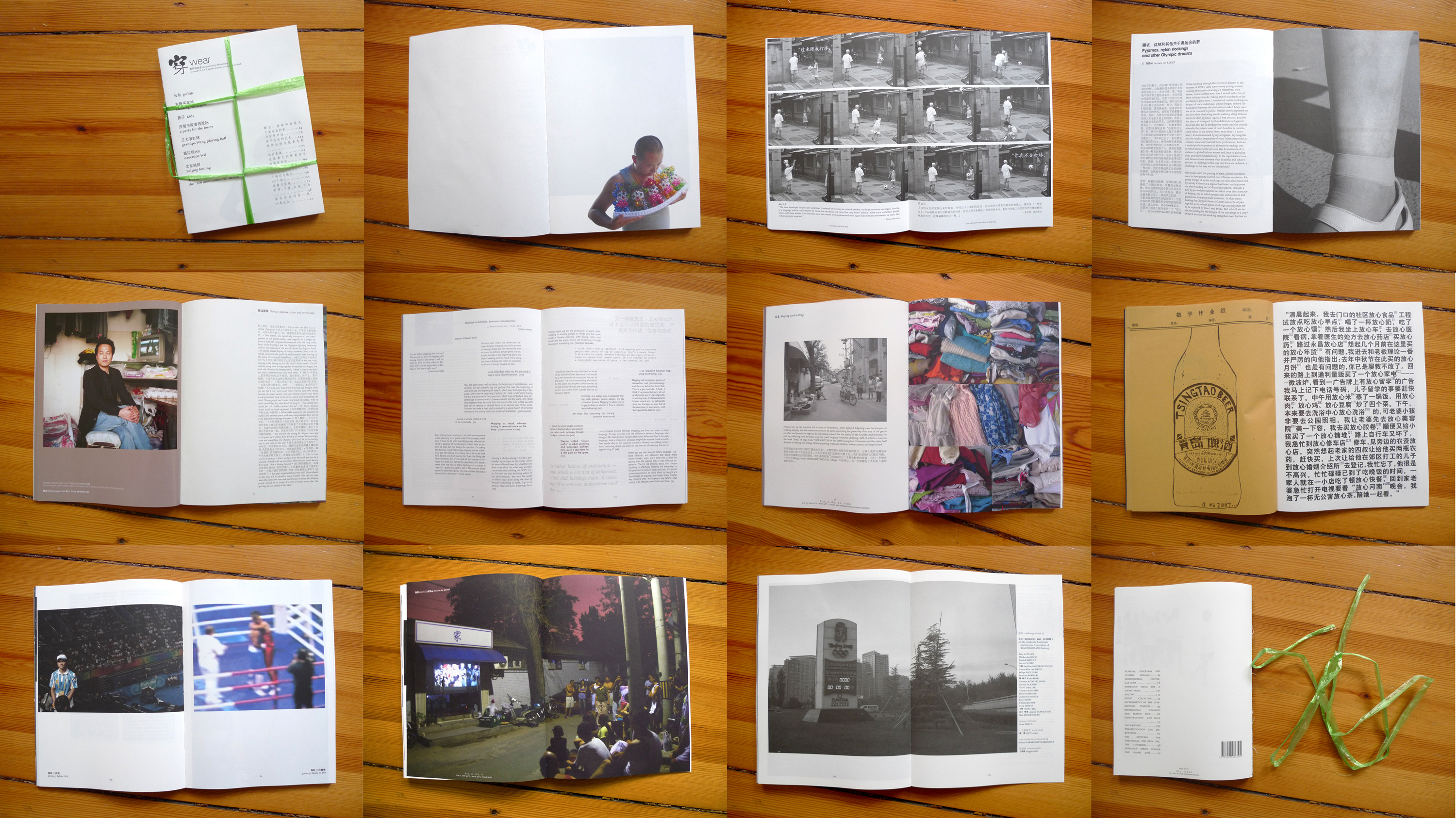

Display Distribute 『CATALOGUE』No. 4, initially intended for production in Guangzhou but by a stroke of luck reverted last minute to Hong Kong, courtesy of Display Distribute

Of course not everyone who is helping to courier a zine or bag of coffee beans will reflect to these scales, but for LIGHT LOGISTICS at least, there is a psychogeography at work which intends to make use of a ‘voluntary surveillance’ as a practice of observation—for a courier, who may for a delivery have to go to a part of the city he/she has never been before—and a question of revaluation: what metadata, or what stories, constitute a logistical record? Why should those working at the small-scale get ousted from participating in transnational, critical dialogues with other (semi-)autonomous practitioners?

Beyond the basic understanding of logistics as ‘moving people and stuff’, documentation and evaluation are the mechanisms which move together to make logistical operations work. This, to answer your other question, is both an aesthetic and an ethical question, and as a framework, platform and loose infrastructure, you could say perhaps that its aesthetics and ethics are premised upon modes of social, political and artistic organisation.

OLS: The way you look at organicity is really fascinating. Perhaps what you mentioned about putting oneself up to "voluntary surveillance" is a way of resistance by reclaiming agency from surveillance as an inevitability in today's age. Your project Shanzhai Lyric can be read as a reassertion of autonomy as well: understanding it through a post-colonial lens, it is a way of rewriting authenticity and cultural imperialism through challenging language. Display Distribute runs from Hong Kong, in which the operant languages include English, Mandarin Chinese, and Cantonese ‑ your website uses both English and Chinese as well, and as a bilingual reader the differences which emerge from translation are really interesting to me.

What is the importance of language and translation in your work?

DD: Resistance is certainly a considered factor, although I don't think it is possible to heroicise our couriers so much in the vein of how they call food delivery workers ‘frontline personnel’ these days. Travel is after all a privilege, and we have been piggybacking upon it, so to speak. But the attentiveness to movement is something that can be read in so many ways—as reconnaissance, instituent practice, or Situationist game, even mindfulness, and that diversity is something that becomes manifest in the project over time, in seeing the various ways that routes are documented, because every courier will attend to it differently. Even myself, having been a frequent mule—what I see and choose to record depends greatly upon the energy required to take notice via images or sound or words. Everything is framed within the banal structures of logistical time and place positioning, but so many things are left out and so many unimportant other details put in. This instability of the data is perhaps part of that resistance you mentioned.

Interns of Hong Kong art space Para Site busy with post-production deconstructions of 『CATALOGUE』No. 4 at the opening of Bicycle Thieves, June 2019; Photo Credit: Lily Yi Yi Chan for Para Site

I cannot speak so much for Shanzhai Lyric as I am not involved with that project; Display Distribute operates as a sort of multi-headed hydra whereby we are not all working on the same things, but as we tried to linguistically experiment with here in a little redux of another to be crucially acknowledged initiative, the Minor Compositions imprint of Autonomedia, there is a kind of ‘gobbledygook’ which we are weaving and wading through and manifests the somewhat perplexing and/or evasive totality. And that is simply to say that there is no such totality, and no centrality as what you point out with the language plays at work. The Chinese and English are not always one-to-one but hopefully they can take on certain forms of nuance for each of their bodies of readers. These shades of Canto-Manda-English that appear are a crucial part of the Pearl River Delta vernacular that has given rise to phenomena like parallel traders and Display Distribute, and with text and textuality being a crucial part of many of our practices, language does become one of the central playing fields. The border between Hong Kong and the mainland is also the first threshold of translation that inspired the initial projects of Display Distribute, and as we’ve seen ongoing since the handover—most recently with the 4/17 Statement by the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the HKSAR and increasingly threatening interpretations of Hong Kong’s very fragile Basic Law—language, the subtle things that get left out and the various ways of manoeuvring through syntax cannot not be considered.

OLS: The process of playing with or navigating language—disseminating texts, copying, pasting, and then perhaps reposting—can then bring about really interesting divergences, and it brings to mind chain letters – which was something you picked out for this conversation as well. Chain letters were a hallmark of the 2000s and early 10s, they continue to exist today in the form of copypastas, but the possible distinguishing factor is that of the encouragement to share, either through motivation of a reward or a threat.

With the various strands of Display Distribute in terms of ideas, performances, exhibitions and partnerships, would you say that the projects have been working towards a more emotive or collaborative mode of transmission that rallies against mainstream or neoliberal modes of consumption? What do these possibilities look like?

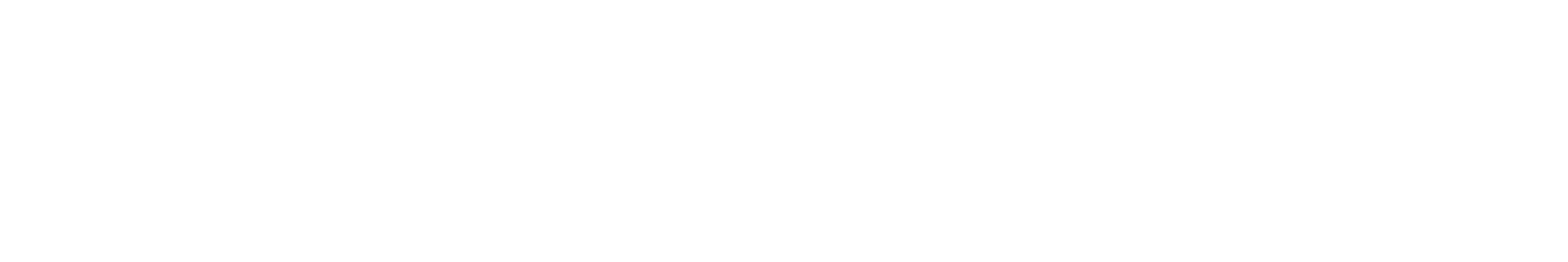

wear journal number one, courtesy of HomeShop

DD: Oh, I’m really happy you brought this up again! I have been thinking about chain letters recently simply because they seem to have made a pandemic era resurgence, sped up for 2020 internet in that it seems—from the perspective of my inbox at least—to have only been a few weeks-long revival. I come from the last mega-transition generation of the world before the Internet (when it was still spelled with capital ‘I’). So those years when chain letters were circulating widely were a time of both naïveté and seriousness in that we took the threats and rewards seriously because it was all so simply new and the repercussions were not calculable. I’ve brought it up again as a point of reflection for Display Distribute because it is an immensely poignant example of the use of affective relations in a networked economy that links money, OL/IRL connections and partial anonymity by way of the simple orchestrated parlance of text. Scenarios are set up for someone to enter into a pyramid scheme, interest group or superstitious belief system, and the end results can never be fully confirmed, but we participate anyway. LIGHT LOGISTICS works in a similar way, juxtaposing voluntarism, contingency and chance with the real tracing of networks and affect. There may be a concrete result in that a book reaches point B from point A, but that is not even the most prized value of the project for us. While we are still running a logistical operation so ‘aim to deliver’, I will still vouch instead for storytelling, cracks in infrastructure, and inefficiency.

OLS: On that note of meandering and subverting, it brings to mind something else you picked out for our chat — the prevalence of book pirating and the presence of pirate archives all over China and Southeast Asia. What do you make of the term “piracy” when it comes to its relationship to ideas such as legitimacy and autonomy? Often, there is a certain image—that of being polished or almost immaculate—when we think of how official archives or museums present our histories. How can making things ourselves (piecing images, texts, and sources together ourselves) serve as an effective counterpoint to the role of said institutions, especially in the context of the internet and the democratisation of access?

DD: Piracy seems to have always been associated with a kind of irreverence for societal norms, notions of propriety and property, which can in many ways be upsetting to any one of us who may have a claim upon something of potential value, whether we are the ones who ‘created it’ or not. If we look into the lineage behind this impulse, there is a history that traces back to the question of the commons and movements of enclosure from 15th century England. But looking from our perspective here in the East, it does beg the question of whether our own forms of ‘legitimacy’ and so-called ‘autonomy’ can only be ultimately defined from these pre-capitalist roots in ye olde England? A number of scholars have attempted to retrace alter-genealogies to this question, and one very articulate and grounded reference I can recommend is Lawrence Liang, Prashant Iyengar and Jiti Nichani’s How Does an Asian Commons Mean. Another is Byung Chul Han’s Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese, one of the volumes in our SECOND(hand)MOUNTAIN(fortress) series, a funny edition that has been scanned by mobile phone and Google translated from the original German. The official English translation came out later than our edition, which we do intend to incorporate into further printings, but for the time being, if an English reader needs, we’ll send the new PDF as well.

One crucial thing that Liang, Iyengar and Nichani remind us is how the first pirates emerged in fact because they were dispossessed from the commons, and as these ‘outcasts of the land’, it was the pirates who ‘would mutineer against the conditions of their work, and create an alternative order challenging the division of labour and of capital’. So this links forward to the latter half of your question, where we re-examine what may have been viewed as piracy and looting and reconsider what can actually be self-initiated, alter-practices of survival and knowledge-testing. DIY publishing practices will always, by virtue of being the testing of ideas in the public sphere, represent microscopic visions of what alternative orders can be created to challenge hegemonic structures. There is a great line from an essay I recently read which says, ‘The little magazine had been and remains, at least for a time, the single most efficient path to the deictic claim that says “we're here, too.”’

OLS: Now that we’re speaking directly to the possibilities a do-it-yourself attitude can afford us, particularly in the realm of publishing, could you please expand a little on what book making means to you? How has your understanding of or relationship to book making or the book form evolved over time?

DD: Looking back now, I think it’s possible to say that the trajectory of my relationship to publishing has run what could be considered a counter-productive course relative to the modernist call for expansion and commercialisation (Bigger! Better! Faster!). Part of my educational background is actually in fashion design, an obviously commercial industry dominated by surface aesthetics and big money, and that collided with the beginning of my work as a so-called artist practicing in China, not academically trained yet with access to the optimistic possibilities of material production available at the time (meaning the years immediately before and after the 2008 Beijing Olympics). This was the period in which we began our own DIY publishing practice in the form of an independently produced journal for the artist-run space I was active with at the time, called HomeShop. It was not a zine, neither handmade nor photocopied, but beautifully offset print with multiple carefully chosen papers, somehow aesthetically still in resistance to commercial appeal but by virtue of being a factory-made production, perhaps it could be considered a way in which a small-scale, marginalised project seeks to stake a claim upon its validity within the archive of contemporary art. We were also saying, ‘We’re here, too’.

But while independent publishing and zine culture has grown in mass appeal over time, China’s rising economy combined with narrowing freedoms means that the space for content ‘at the margins’ or ‘between the lines’ is being squeezed out. In recent years, I have been refused as a client both by low-cost digital printing shops as well as offset factories, the former because my order (different colours of covers for different titles) veers from the producer’s cost-efficiency standard (too 麻煩 mafan!), and the latter because printing sensitive content would risk the factory being forcibly shut down by authorities.

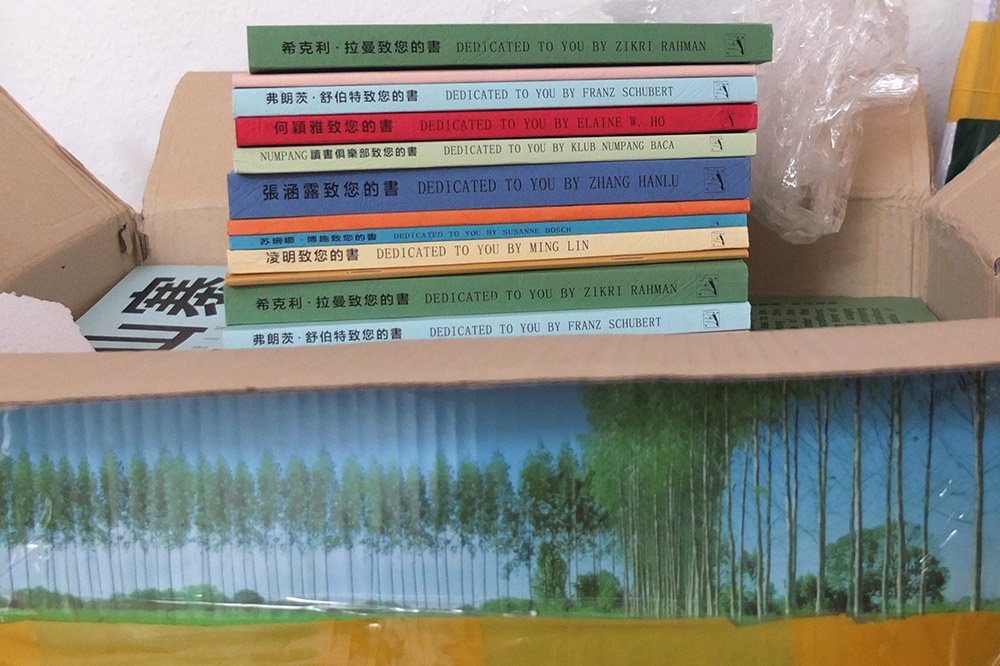

So in a way, our status as pirate, smuggler and hacker is exactly as was written above, where we have been ousted from the market and accessibility to resources diminished. To continue doing what we would like to do, it seemed to make sense that we should in that very old school, Marxist sense, ‘take back the means of production’ ourselves. So that means trying to make more books ourselves, to try to reconsider the balances between the material craft of book production and its content without being nostalgic or trying to glorify the handmade. To go back to the initial reflection of counter-productivity, this means that over time, our print-runs are getting smaller and the whole process from start to finish is slower. But as with LIGHT LOGISTICS, obviously we don’t have a problem with that.

Digital print-on-demand copies of the Display Distribute ‘SECOND(hand)MOUNTAIN(fortress)’ imprint

OLS: We’ve touched on quite a few ideas throughout this interview including small batch productions, inefficiency as an alternative framework, and the allure of DIY culture. There are so many strands of inquiry to your work with Display Distribute, and these research questions or interests are constantly evolving. To wrap up our conversation, could you please speak to whether there has been a philosophy, a praxis or even an attitude that binds all of these interests together?

DD: How about answering your question with a praxis of the question itself? The diversity of inquiry can on one hand simply be the distractedness of many interests, many references and/or inspirations, maybe otherwise simply giving space to the multi-headed hydra of collaboration. But a most general formula is simply beginning from the question itself—questioning everything, second-guessing all. It’s a possibly painfully ambivalent route, but it’s also the starting point for trying things a little bit differently, imagining and practicing another possible way.

Display Distribute is a thematic inquiry, distribution service, now and again exhibition space and sometimes shop founded in Kowloon, 2015. Seeping via the capricious circulation patterns of low-end globalisation into other subaltern networks and grammars, recent activities include the experimental infrastructure LIGHT LOGISTICS, poetic research and archival unit Shanzhai Lyric and a peripatetic radio programme of hidden feminist narratives known as Widow Radio Ching.

© Singapore Art Book Fair 2025. All rights reserved.

For further enquiries, please contact us at info@singaporeartbookfair.org.

Singapore Art Book Fair is organised by

![]()

For further enquiries, please contact us at info@singaporeartbookfair.org.

Singapore Art Book Fair is organised by