A collection of conversations with a diverse range of local and regional creatives

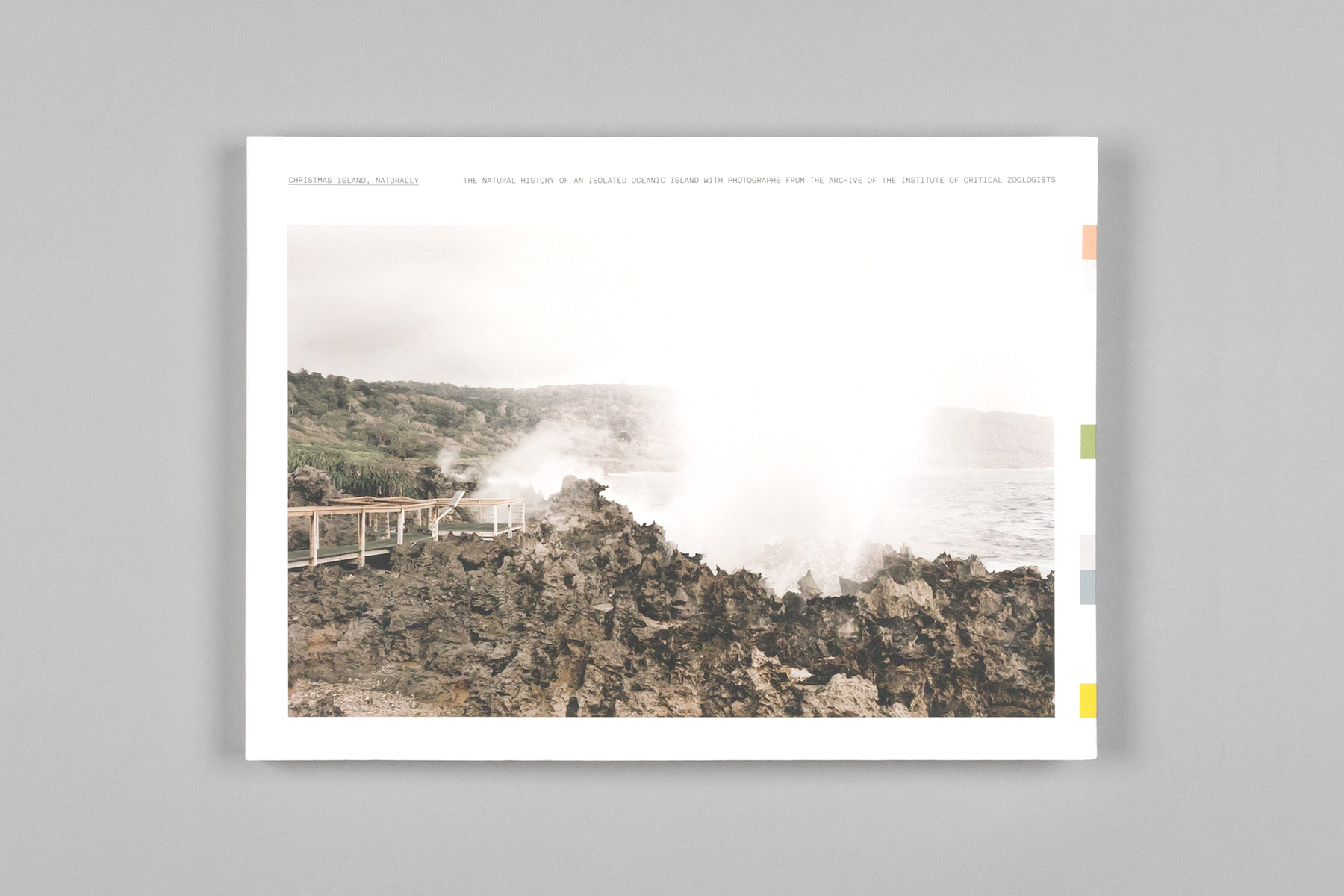

Library Conversations for SGABF2020

We examined the systems that support art book making and independent art book publishing in Singapore and the region.

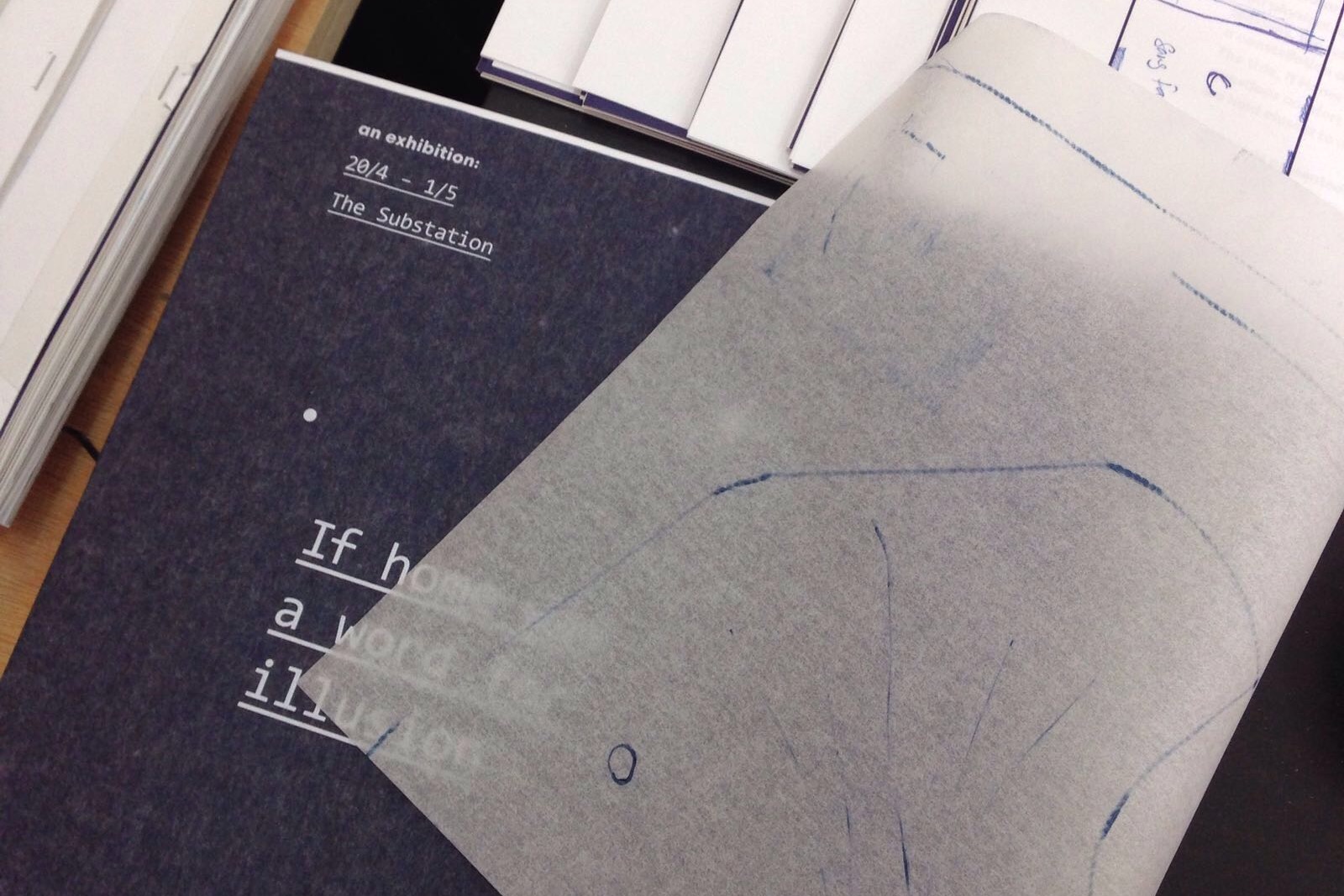

A Closer Look for SGABF2019

We gathered perspectives on our zine and art book culture, and discuss the possibilities of self-publishing today.

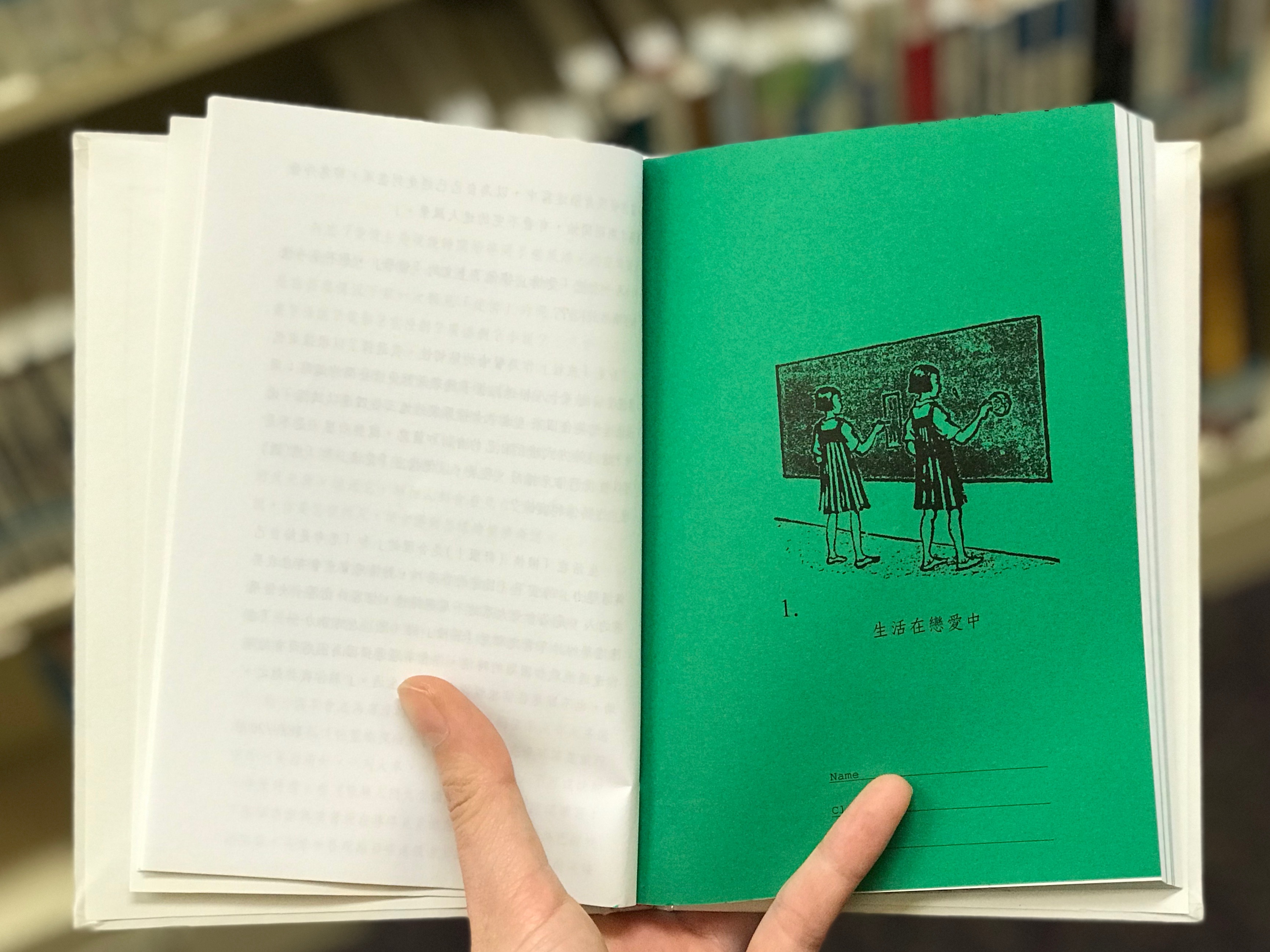

21 Creatives for SGABF2018

We sat down with 21 creatives of various disciplines to learn about their practice and asked each of them to fill up a blank page in a notebook.

CURRENCY

Photo Credit: Currency

Photo Credit: CurrencySGABF: Can you bring us through the principles of Currency and the studio dynamic? How has the studio dynamic and design practice of Currency evolved?

MELVIN (M): When the idea of starting something independent first started, the idealism that comes with collaborative models that favour flexibility and avoided any sense hierarchy. This led towards something sustainable hence a more "traditional model of a studio". The team and dynamics have grown. With that also the design practice and a different model of attending to each other's strengths and interests. Today, our work fundamentally lies in dedicated process in developing strategy and good ideas, the developmental process is team-driven where depending on strengths, we add value to different aspects of projects.

SGABF: When tackling a brief like SGABF, what were your considerations when you first took on the visual identity in 2018 and how is it different this year?CHARLIE (C): The design phase started a lot later in 2018. This year, it feels like there has been a lot more time to ideate and develop the direction so our considerations are shaped less by pragmatics and time constraints than they were before.

M: The brief that we got for SGABF2018 was to, first and foremost, create an entirely different impression from the previous editions. We worked alongside Renée to rethink what a book fair can look like on an international level. As much as we wanted to challenge how an identity for a fair can look, we always discussed how the eventual design had to draw a crowd that was and still is interested in alternative forms of books and printed matter.

An art book fair is often quite eclectic so we came up with a concept that hinged on two things – using different typefaces or versions of a font to capture that sense of diversity and adopting an expressive ribbon that encircles around a book spine or bookmark for the key visual. It captured the fun nature of an event like SGABF while remaining dynamic and easily adapted across different sizes.

Photo Credit: Currency

Structurally, the identity for this year shares a closeness to the previous one. This year, we expanded on the central part of SGABF that is the word ‘book’. We like how the double ‘O’s can resemble two pages of a spread out book and move away from the fixation on book covers.

SGABF: The identity and design focus for SGABF2019 seems more graphic-based, whereas last year’s seemed to touch more on typography. What were the factors that motivated or contributed to the current approach?

SHENG YONG (SY): To bring out the collaborative spirit of SGABF, we thought it would be wise to get different people to express their interpretations of the word and its possibilities through motifs. Surely it’s more visually driven at one glance from the content created by collaborators. However, it’s a framework that makes the identity more content-driven and our graphical contribution actually takes a backseat. What we’re doing is putting the makers and creatives at the forefront.

M: The actual event itself doesn’t actually take place for a very long time – only three days. The identity focuses on campaign content. We established channels of communication that are key to how people understand the fair before it happens and it needs a consistent presence online because of the open call period and campaigns prior to the festival. That’s when we realised that the approach should be centred around that. It’s important for the audience. I think every edition will get better as we identify what works and what doesn’t. It’s important for us to explore and experiment with different strategies, and find out what makes the biggest impact.

SGABF: The idea for the motifs came from the desire to expand conversations and possibilities – a key principle of the Art Book Fair. What were other reasons for implementing them? Has the progression of this element so far met your expectations as to how it would inform audiences about the event?

M: I enjoy how the features as part of A Closer Look are sometimes a very intimate read and in other times, revealing. It aligns with what we are trying to do for the design – ensuring that the contributor or the feature is kept central. I think that’s the beauty of having a structure that’s purposeful, as a gateway to align everyone together. It’s representative of the art book fair, where multiple practices share a stage but what brings people together in that single space is the format of books.

SGABF: Currency emphasises on process and strategy first in design. How has this principle informed your work?

SY: We have a principle of not taking aesthetic at face value. We start by thinking around the needs of the project and expand on that before going into the visual aspect of what we do. We spend a lot of time communicating what we think is best for the brief. When everything approved comes together, we hope that the outcomes we create are sharp, appropriate and relevant. Visuals and graphic style wise, we are known to be quite experimental for some but overall, our works are quite diverse.

Photo Credit: SGABF

SGABF: Does the consumer part of you inform the design practice?

C: Being a consumer makes us think, as designers, about what people are looking out for. We end up having quite a strong idea about what stands out, and what would pique people’s interest. It’s not just the visual aspect or an effort to increase clout, which is quite telling about our principles and ideals that we try to bring into publications.

M: As much as our outcomes may hint at certain approaches, we usually start by asking a lot of questions, sussing out the audience and purpose of project. In some ways, we are servicing our clients when responding to a brief. However, we consider strategy and are also open to very experimental or non-conforming ideas. We enjoy the process of experimentation, especially when it feeds into the purpose of the project. The important thing as designers is that we don’t end up proposing something that is way off.

C: That’s right. I don’t think we do experimentation for experimentation’s sake.

M: We don’t usually begin designing very early on in the process. We refrain from jumping into the aesthetics from the get-go. I don’t reckon it’s always about problem solving either. I think we need to figure out the tone, ideals, objectives and consider if design can help.

SGABF: How do you deal with the concern of authorship as designers? Would you say that’s a major setback in your process?

M: The questions that come about with the discussion of independence and authorship as designers include: how much influence do we have in the outcome? How are we engaged as service providers? For example, the procurement process for many jobs centers on the extent of application. With a starting point like that, talking about your own personal interest or ‘authorship’ is close to irrelevant.

Photo Credit: Currency

SGABF: So ultimately, where does autonomy lie in design practice?

M: At Currency, the autonomy lies in the fact that we are a small studio, and the quality of our output depends on how we put our heads together. An idea can come from anyone in the studio, myself, or from the client. Ultimately, our sense of autonomy and independence lies in our approach and derives from our learning process. With the pervasiveness of digital technology and given the accessibility of various digital resources, there is also a problem of iteration.

C: This is one of our principles – use anything that we find online responsibly. We don’t want to rip anything off. Obviously it’s something you can’t skip out because resources can be inspiring. But I think there are standards that we set for ourselves – how inspired are we by a certain thing that we see online, for example? How many degrees away we should be from our inspiration is something that we’re very conscious about, whenever we look at something and find it interesting. And that’s something you can empathise with as well – if you notice your work inspiring something else. As a designer you do value that, if you can see that the person has strived to not completely rip off your idea, or done something a bit further removed.

M: I think looking at references is one small area of our process, if we’re stuck creatively. A lot of the time, we don’t. Perhaps, once in awhile, when we do encounter a creative block, or maybe when we’re just not sure. Our turn to references is usually prompted when we’re not sure how should we style a certain aspect or element of a project. We look at how people do it to know. It helps to accelerate that process and raise more necessary questions that we have about something we’ve not done before.

C: It’s the same as looking at a physical book. We’re constantly playing around with layouts, hierarchy, images, seeing how it’s done, referring to the books that we have lying around. Actually we do that more than Pinterest. Usually our search is very specific, like how is this done in a certain way? And then we see a possible approach, and we do a version of it in our own way or in a way that’s responding to the brief.

Photo Credit: Currency

SGABF: Based on Currency’s practice, experience and observations, how would you describe the characteristics of a critical graphic design practice – especially in the context of a landscape like Singapore?

M: I’ve talked to a few friends about critical design, or ‘critical’ as a term. I feel that there are many ways to define or characterise it. Everyone has different interpretations to critical design. Sometimes it’s a style or the nature of design practice. It’s difficult to talk about a term that is subjective or continuously evolving, especially if we see it as an approach.

Critical design does align itself to the idea of ‘ugly’ or ‘visually abrasive’ works. I think that if it’s appropriate, or if it answers a certain brief, then anyone may consider doing it. Especially in the arts, aesthetics can be a way of questioning established forms of looking and iterating and can be channelled to express beliefs, sentiments and political positions. Certain design elements can be treated in such a way, be it choosing design as a kind of conceptual gesture or artistically.

SY: In the context of our landscape for design, I guess Singapore’s scene is still pretty young. There is still quite a lot of exploration to be done. People are still pushing boundaries. To a certain extent, not subscribing or conforming to the usual design practices might be seen as ‘critical design’ because it’s going against the grain.

C: I think we see more and more people having different takes on design. So they don’t necessarily want something that’s beautiful and conforms to the most widely understood definition of good design. They may want something that’s interesting and puts a different spin on design. That could be what ends up getting called ‘visually abrasive’. People’s tastes and the discussions that they are having about design seem to be evolving more and more.

M: I've visited quite a few grad shows recently and its exciting to see graduates go about rethinking design approaches here. It’s evident from the work showcased. It shows people are ready to talk about it. I still don’t have all the answers yet, even having read articles and had conversations about it. But then again, perhaps when it’s clear, it’s no longer worth talking about it as it won’t be a particular thing in itself anymore. That said, the fashion side of visual culture is always evolving and reprising. What can be considered critical design three years ago, a time when I hear the term said more often than now, may not be the case today.

SGABF: As collaborators of SGABF, what are some actions you feel that organisations, platforms and spaces like ours can take to extend more room to interdisciplinary makers and practices in developing their craft?

M: The platform that the SGABF provides help to motivate all levels of the book-making process. We have the artists, producers, designers and printers who are all integral to the form. An initiative like SGABF that happens cyclically imbues a culture of appreciation when makers know that there is a platform to showcase their work. It might motivate someone to develop their craft within that community.

SGABF: Finally, what’s the most interesting zine or art book you’ve come across?

C: Us Blah + Me Blah

M: Mould Map 3

SY: Notes on Ghosts, Disputes and Killer Bodies by Gabrielle Kennedy and Jan Boelen

Currency is a Singapore-based design studio that offers creative direction and content.Extending from a project’s theoretical underpinnings, Currency seeks to work through contextually informed approaches to produce novel outcomes with an experimental flair.

Photo: Courtesy of Artist

SYAHEEDAH ISKANDAR (SI): I’m currently doing my MA in History of Art and Archaeology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Before that, I was holding a full-time position as a Curatorial Assistant at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) Singapore from 2014 to mid-2018 before leaving for my studies. I was also juggling independent projects on the side from developing exhibitions to embodying another persona as a DJ.

I co-founded a female DJ collective, ATTAGIRL! in 2013 alongside Amanda Ang and Serene Ong as a platform for us to support women in underground electronic music as well as VJs, visual artists, music producers and performers. Though with so many things going on, I have taken a back seat in the collective for some time now, so I let the girls run the show without me. I would say everything is currently on a standstill. This was a decision I made when coming to London. I was at the point of exhaustion and needed to recalibrate. I wanted to feel like an audience again but more importantly, to have the time to just read and learn.

School has been challenging but absolutely enriching. As of now, my current research is thinking about modes of visuality within the Southeast Asian paradigm. I am absolutely grateful to be in this current state of mind now, so I am embracing these moments as they come.

![]()

Photo: Courtesy of Artist, Publication Design by Fellow

SGABF: Hi Syaheedah, for a start could you tell us more about your practice and what have you been up to in London?

SYAHEEDAH ISKANDAR (SI): I’m currently doing my MA in History of Art and Archaeology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Before that, I was holding a full-time position as a Curatorial Assistant at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) Singapore from 2014 to mid-2018 before leaving for my studies. I was also juggling independent projects on the side from developing exhibitions to embodying another persona as a DJ.

I co-founded a female DJ collective, ATTAGIRL! in 2013 alongside Amanda Ang and Serene Ong as a platform for us to support women in underground electronic music as well as VJs, visual artists, music producers and performers. Though with so many things going on, I have taken a back seat in the collective for some time now, so I let the girls run the show without me. I would say everything is currently on a standstill. This was a decision I made when coming to London. I was at the point of exhaustion and needed to recalibrate. I wanted to feel like an audience again but more importantly, to have the time to just read and learn.

School has been challenging but absolutely enriching. As of now, my current research is thinking about modes of visuality within the Southeast Asian paradigm. I am absolutely grateful to be in this current state of mind now, so I am embracing these moments as they come.

SGABF: You were previously the Curatorial Assistant at NTU CCA Singapore. You’ve also curated If Home was a word for Illusion (2016) and Nyanyi Sunyi (2018). As a curator, what’s the most important thing to note in terms of joining forces with artists to put up their works based on your direction for the exhibition?

Photo: Courtesy of Artist, Publication Design by Fellow

SI: Not many people knew this but for the exhibition in 2016, it was the artists who approached me, and I was more than happy to take up that opportunity. To have that kind of support and faith, especially since three of the artists did not know me prior to the exhibition, is what I think builds meaningful communities.

To me, intention plays a huge role in that equation. In the Malay language, we call it “niat” which is always placed somewhere close with “ikhlas”. Ikhlas basically means sincerity. Sometimes we get caught in the process of trying to make the project successful, so much that we end up ignoring the hard questions on why we do what we do and to whom the project is for. It is in moments of disagreements or setbacks that I find these reflections (of niat and ikhlas) important for me.

Working at NTU CCA Singapore provided a different experience as opposed to working independently, and there were limitations on both ends, but I was aware of my privilege of being part of an institution. I had more access to resources but having worked in both the Exhibitions and the Outreach & Education departments, one thing that struck me was the challenge of sustaining organic engagement with marginalised communities – whether they are underprivileged, under-represented, physically or mentally challenged. A part of my job was leading tours for students of varying ages and backgrounds, and it shows by the questions they asked––their own accessibility to art depending on what school they were from. Coming from a neighbourhood school myself, I saw a clear distinction as compared to the elite schools. We still have a lot of work to do in that area.

SGABF: Exhibition catalogues often provide context to curatorial perspectives and the works of artists. Having been involved in print publication work yourself, how do you weigh the prospects of printed matter coming together with exhibitions?

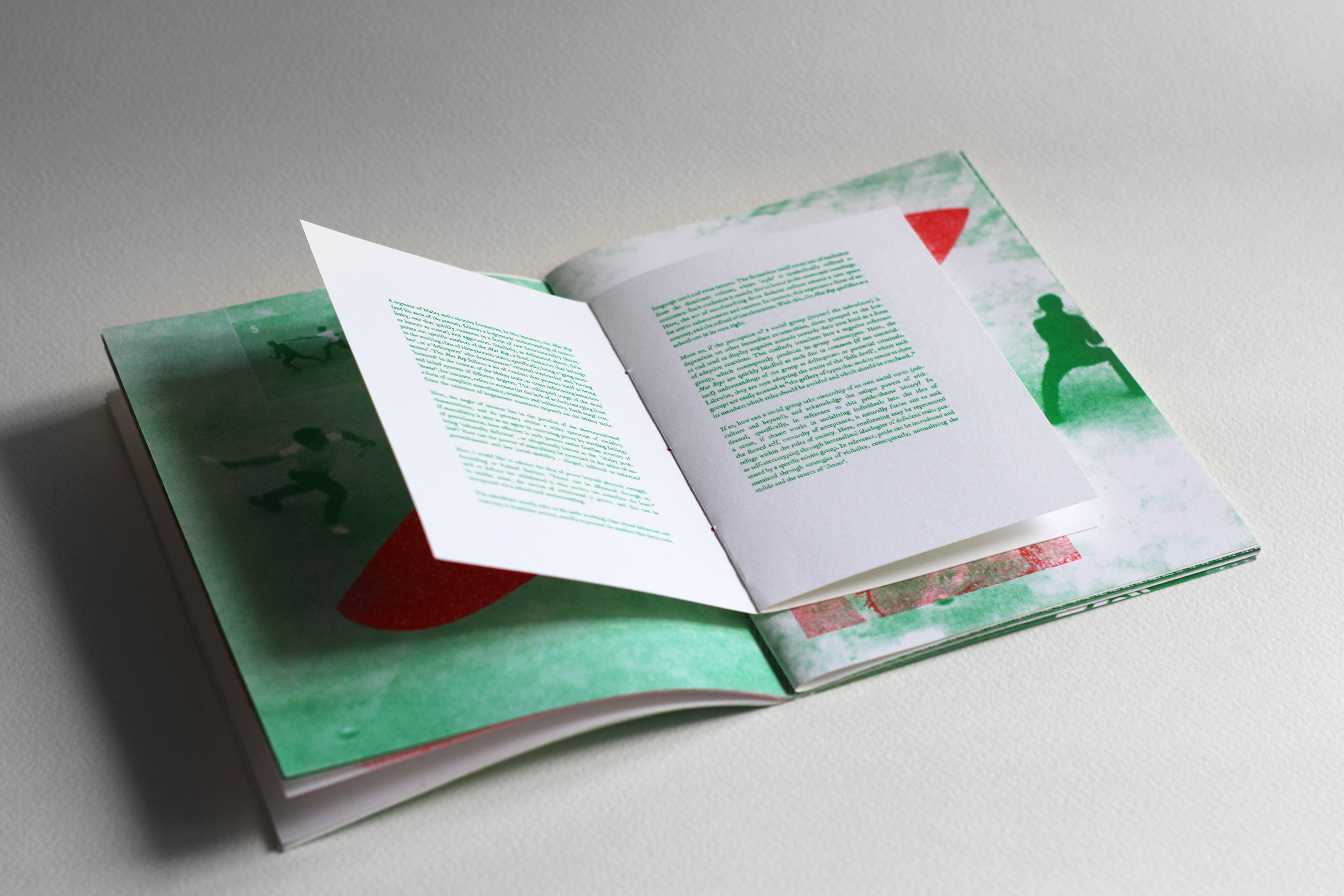

SI: Exhibitions do not necessarily provide solutions, but they can invite discussions on the issues that are presented by the artists or curators. Printed matter allows that discussion to take place as an extension of the exhibition that is no longer confined to the restriction of space and time. It is also a source of documentation which I believe is important especially for future research. You would be surprised by the number of exhibitions that have been put up in Singapore featuring the same themes over and over again. It’s unfortunate that these exhibitions rarely have the opportunity to speak to each other. This was something my peers over at Sikap (run by Zulkhairi Zulkiflee and Nhawfal Juma'at) realised too, which pushed us to do a joint publication launch for our exhibitions; RUANG(2017) and Nyanyi Sunyi (2018). It made sense for us. While these ideas may not be new, printed matter can help integrate new modes of thinking which is reflective of contemporary discussions. As archives, they can bridge old and new discourse for the future.

SGABF: How would a long form publication (in a zine, art book or monograph format), for example, take shape in the context of curatorial projects and exhibitions?

There is definitely more room for experimentation which I think a lot of exhibition catalogues today have started to embrace. The content is no longer confined to essays and research papers. Materials such as poetry, annotated essays, visual essays, handwritten letters are some of the unconventional content that I have integrated into publications from the artists and collaborators.

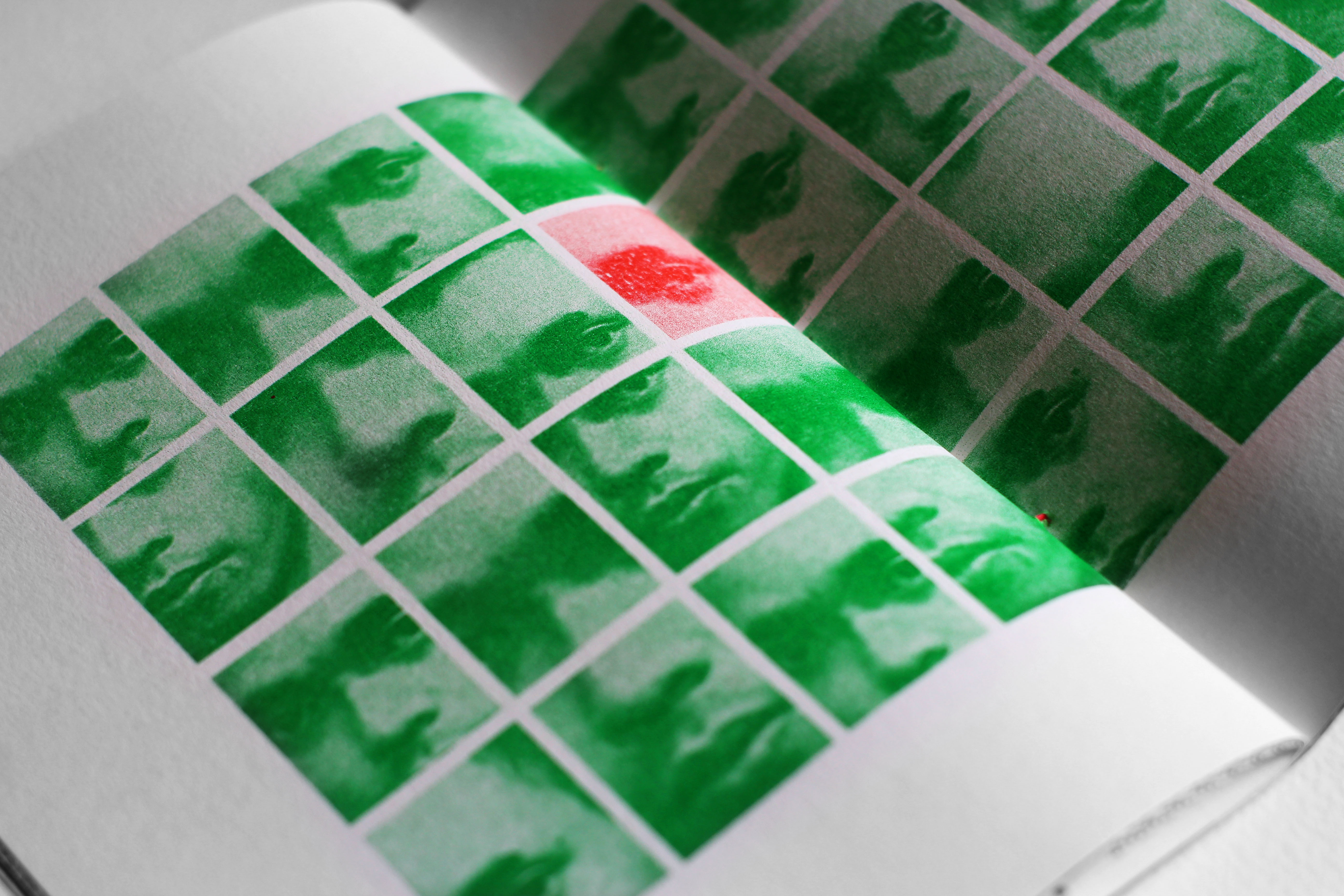

For Nyanyi Sunyi (co-curated with Kamiliah Bahdar), we had an amazing designer, Zachary Chan, who sincerely believed in our project. Some of the content was difficult to work with, but we trusted him anyway. His design bridged both textuality and visuality without losing its purpose as a post-exhibition publication. I have worked with designers on an institutional and independent level, and I find letting them roll with their own ideas often times turn out to be best collaborations.

SGABF: In relation to the previous question, how necessary is wide circulation of ideas and opinions from communities represented by these exhibitions? What inadequacies have you observed from creative showcases?

Photo: Courtesy of Artist

SI: It is necessary for sure, but the challenge is sustaining the conversation after the project ends. Being able to work in the creative industry for some peers who share similar sentiments as me is a luxury. We do not have the luxury of churning exhibitions after exhibitions. Creative showcases whether in forms of exhibitions or publications are expensive and requires funding to begin with. Conversations eventually die out, and there are many reasons for it – people move to other interests, projects, lack of funding, priorities shift, and so on. Publications get shelved.

I had a full-time job and supportive colleagues who allowed me to do my own projects outside of the institution. It also helped that my parents were emotionally supportive. Support systems such as mine were critical but what about those who do not have such accessibility? Igniting conversations is one thing, but does it necessarily provide solutions? Apart from publishing articles, we need more spaces where we are allowed to come together as communities to speak about these issues. We need diversity in voices as well. More producers, cultural workers, curators, arts professionals from diverse socio-economic backgrounds. Otherwise, we are stuck in an echo-chamber, speaking to the same group of people and leaving out opportunities to sharpen our own ideas further.

Personally, I consider myself part of the problem too – as someone who offer no solutions. This is an issue that needs to be discussed openly. Apart from providing spaces for marginalised communities, we need to re-strategise our modes of working given that climate change is the most urgent issue of our time now. Unsustainability is entrenched in our system. Art exhibitions are no exemption as they can be wasteful. With panel discussions and symposiums, if conversations are confined between the educated and socially mobile, is it really going to change anything?

The discussion on printed matter within the foreground of these issues has to start as well. I personally love print, and nothing beats the feeling of running your hands physically through a book. But we have to start asking the hard questions now. How do we move forward and celebrate print in the face of the biggest ecocatastrophe our generation will ever face? Our children’s future is being robbed in front of our eyes. It is more than just using recyclable materials for the sake of feeling better about ourselves.

SGABF: Have you had to go through a process of reflecting upon your past experiences in curation, art, music and writing in order to move forward with your current creative practice? What other processes did you have to go through that have informed your work and artistic beliefs today?

SI: To be in reflection after being in production mode for so long was a tough adjustment for me. I do sometimes miss performing on the decks as it was a form of outlet for me. I have been working since completing my O’ Levels to support myself through my diploma and degree years. There were struggling points, but I am grateful for them. These experiences are not unique to me, and I know of many peers, especially artists who resonate with these struggles. Having had similar conversations with my peers, a lot of these anxieties also stemmed from not wanting to lose momentum or the fear of missing out. By 2017, I was burnt out. It felt empowering to tell myself that I needed to take a step back.

Being in London, (while observing Singapore from afar) in an environment like SOAS with a strong student union, allowed me to be an active participant in social issues and discussions––from climate change, rethinking new modes of decolonisation, tackling racism, class inequality, and so on. Although the future is uncertain for me at this point, attending these discussions have informed and made me rethink my own ideas and practice.

There were definitely moments where I wished I had spoken, wrote and done things differently in past projects but I have learnt not to dwell in it. If anything, those lessons, mistakes, failures were necessary. People can hold you accountable for your naivete, and that is okay. We are not infallible. If we can sustain conversations that speak to us passionately, our language will in itself will mature and develop into better tools of expression.

SGABF: Finally, can you recommend up to three zines/art books that have had significant impact on your practice so far?

SI: It’s difficult to pin down absolutes, and this is a fairly personal question to me. I remember someone asking me a similar question on my “current reading list” to which I responded by asking if she was trying to read my intelligence.

So instead, I would like to make a tribute to three of them that remain unread on my shelves. These were some of the few that were recommended to me by close friends within the past year or so. They will be read soon, I hope:

Lapdogs of the Bourgeoisie: Class Hegemony in Contemporary Art edited by Tirdad Zolghad, FIELDS: An Itinerant Inquiry Across the Kingdom of Cambodia edited by Charlotte Huddleston and Roger Nelson, Bubble Gum & Death Metal (BGDM) Issue 1: Sharing by Denise Yap

Syaheedah Iskandar is undertaking her MA in History of Art and Archaeology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and was previously Curatorial Assistant at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (2014 – 2018). She is currently researching and writing on visual theory within the paradigm of Southeast Asia. She is the inaugural Emerging Writers’ Fellow for the academic journal Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, working on an article about ghaib (unseen) within the vernacular Malay world. She also embodies another persona as a DJ, under the moniker of Jaydah.

SUPERNORMAL

Photo Credit: SGABF

SGABF: Hi Kian Peng and Ivan, can you tell us more about your work at Supernormal and your design practice, Modular Unit?

IVAN (I): I take on a number of things, such as post-production, print and ceramics.

KIAN PENG (KP): Ivan does more than that. He is a ceramist and is part of the ceramics collective Weekend Worker. Modular Unit is a design studio we both founded. We do a range of things, such as publications like the one we recently created for Singapore Design Week. We also work on branding and websites. Modular Unit also specialises in exhibition designs, interactive installations and motion graphics.

I’m a designer and an artist. Ivan usually handles more of the print aspects of design while I take on the digital side of things. We both teach on the side. Artistically, I focus on media art and new media, seeping into the work we do at Modular Unit and our gallery space, Supernormal.

SGABF: What is the value of zines and self-published materials to you?

KP: To me, there is something quite precious about self-published zines in a way that’s similar to B-grade movies. Self-published zines have no commercial pressure to perform. They are more about communicating and expressing certain concerns we have. They have a unique voice that is very pure and focused, as compared to other zines that might serve vested interests.

I: I think different sentimental values exist for self-published materials, depending on the underlying message. There isn’t a brief to answer, and it’s more of a freeflow approach. Self-published works can, however, be quite stressful if you are looking at producing something really comprehensive that takes a longer time to produce. In short, it’s about the value and how much you want to put into it. I personally find self-published zines more realistic in terms of content.

KP: Design wise, there’s also a lot more freeplay. Looking at Rubbish Famzine by family collective Holycrap, the things they do might never be approved in a commercial context because it is so crazy and totally nonsensical to produce. Yet, for them it is about the process and a family undertaking that creates value. These things are typically not commercially viable unless it is part of a really special advertising campaign.

SGABF: We are interested in the delineation of Modular Unit and the Supernormal space. What was the initial impetus behind the creation of the latter and how might that have changed over the years? Ideally, what do you want Supernormal to become?

KP: Ivan’s friend was blasting a message that there was a free space and wanted to find out if anyone was interested in doing anything with it. That led us to viewing the space at 333 Kreta Ayer Road, which eventually became the first location for Supernormal.

Photo: Café CUP by Atelier HOKO, Courtesy of Supernormal

I: We went down without the intention of renting the space. We just wanted to see it.

KP: We felt that there was potential and approached the architect renting out the space. We suggested that people didn’t really have a reason to visit the block, which might explain why it’s difficult to let the space out. We thought of doing a series of pop-up shows to drive traffic for the place. After about a month of doing it, we decided to continue because the experience was quite valuable for us. The ethos is similar to the creation of self-published zines – existing as a platform for alternative and emerging makers who might lack access to more established spaces. The short answer is: There was no initial impetus for Supernormal. This is something I find common among independent and artist-run spaces in Singapore. Things just happen.

We don’t have a clear five or ten year plan. Our hope is that it will one day grow to become a mid-sized museum or gallery, like spaces in Korea and Japan. That is already an upgrade from artist-run spaces. We would love to build a design studio at the top floor. However, this is still a faraway dream. Currently, our focus is on the ground activities and events. We aren’t so interested in being a commercially-viable space at the moment.

SGABF: A significant ethos of the Supernormal space seems to be a desire to present experimental and offbeat projects. How do you determine works like these?

KP: We don’t have a specific guideline. A lot of it is based on gut feeling. We want to show experimental and newer ways of approaching things because design and art in Singapore feels very safe, most of the time. Those who are often experimental are marginalised, especially in design. A common thread across different institutions, at least in the schools Ivan and I have been in and taught in, is that experimental works are somewhat discouraged. There is a lack of focus on process, whereas results are prioritised. The space tries to promote and encourage process-driven works locally.

I once received a question from a student from my time at Nanyang Polytechnic’s School of Interactive and Digital Media. It was casual, but left a strong impression on me. I was teaching an experimental module and a student asked me, “We learn all these things, but where are we going to show them?”

That got me thinking about how we lack spaces to display such works in Singapore. For artists, even though the landscape isn’t fantastic, there are still spaces to work with. However, there are no specialised spaces that encourage experimental, off-beaten or new genres for design. This is the same with magazines and publishing.

SGABF: A number of shows organised by Supernormal have explored the intersection of technology and art, namely your collaboration with SAND Magazine in 2018 (Technology in Art) and Adaptations at Gillman Barracks as part of the 2019 Singapore Art Week. Why the interest in this area and how do you think it has affected the nature of zines, self-publications and other mediums?

KP: The nature of our self-initiated showcases usually comes about from our perspective of technology. Before Modular Unit was around, we were part of an audio-visual group, PMP. That was an audio-visual performative collective that used technology, audio-visuals and live music, which then eventually led to Modular Unit. My own practice also explores the intersection between art, design and technology.

With Supernormal, we wanted to highlight the idea that technology is very much a medium like paint, and can be adopted as a form of material for art-making. A lot of Singaporeans still see technology as a concept belonging to the fields of science and engineering. It’s confusing for them to see technology being used in an artistic context.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Supernormal

That’s because the world we live in is becoming more and more technologically-driven. Everything we see, hear or converse with is becoming very mediated. As artists and designers, we need to start getting our act together. There tends to be an over-romanticisation of the print medium that we fail to see the potentialities of technological mediums. With the Technology in Art and Adaptations, we were basically trying to showcase works that used technology in meaningful, poetic and contextualised ways. I think there are a lot of works using technology just for the sake of it, even in the arts, so our aim is to present a different perspective to this whole phenomenon.

Today, we have the luxury of perusing aggregated content from social media channels. The greater volume of content changes the way we look at things. Because of that, we need to start looking at what we want technology to do for us, and understanding how it works in order to have control over what we are trying to produce. Otherwise, we would be caught in a perilous situation where users are being manipulated with all these information. For example, the only source of news for many people is Facebook. That is very dangerous because a lot of this news can be biased, and fake, or entertainment news which is very rooted in a journalistic kind of approach. When you do that, your perspective starts becoming very narrow. This also applies to zines.

Online zines are becoming more common. These days, many people are looking at whether zines are even a thing anymore. That’s because of the way content is being served. Blogs and websites are essentially zines, format wise. To truly determine the future of physical zines, a lot of testing and understanding of various concepts around content circulation and consumption have to be done.

I: I think about how online and offline retail might function in the future. Both platforms have to work hand in hand. How will zines negotiate with this relationship? How can makers coordinate the content in both ways? I recently shared a conversation with a friend – we were discussing book designs and formats. Can a book be displayed in newsprint? Perhaps a toilet roll with one column to read? Whatever it is, they still possess the same function of delivering content.

SGABF: The advent of technology can bring about a destabilising feeling, with things being in constant flux and change. Some practitioners choose to veer away from it, revelling in more ‘primitive’ forms and methods while others have actively embraced it.KP: I think there has always been this phenomenon since the Industrial Revolution. The Luddites refused to acknowledge and adopt technology as part of their lives. Of course that didn’t work out too well. I think what some practitioners really enjoy is the process of printmaking and the tangibility of the format. That is also not to say that technology is entirely rejected. In a way, there is still a lot of room to negotiate around that. The other school of thought is integrating the idea of zines into a more technocentric society. These are two completely different ideas that might eventually form into something else.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Supernormal

Zines might adopt a new term in the future, where content is served in a completely different way and exists in a virtual world we don’t know of yet. For many years, magazines have struggled to tackle such the dialectic between online and offline. Many magazines have closed down because of the lack of sales.

I: Personally, the physicality and materiality of objects really enhances the sensations of touching, flipping or smelling these items. I think practitioners continue with their approach just because they can’t let go of such feelings and emotions associated with these sensations. Perhaps they find that worth preserving. I think about QR codes and hashtags that are now printed in physical books. These would not make sense in the past. This might be a way to keep these two forms intact – online yet retaining the tangibility of the physical format.

KP: Digital formats, too, are struggling to achieve the same kind of emotional quality. It’s like writing with a pen and typing on a keyboard: these are two completely different modalities that affect our reading behaviours. The focus and perception of the content changes as a result. The people in tech are still trying to figure out how they can reconcile the digital experience with print media.there have been many attempts to research and execute tangible media. As of now, there is still no viable replacement for the print format.

SGABF: The Internet serves as a free or inexpensive space to upload any form of content whereas the cost of printing might prove to be a barrier for printed matter. However, some makers have found that there is a form of layer that filters through, resulting in greater thought put into the production process.

I: That is true. Since the production of a book is expensive, one might practice reducing unnecessary information in the printed form. That leads to a collection of useful, functional content that is being circulated. In comparison, online content might be less digestible for readers due to the large pool of information.

KP: Keeping in mind that the way we write online is different. Curated websites depend on linking. In print media, the ethics and approach of writing switches up. Writers and curators have to exercise a lot more thought with their content. That said, newer generations are looking at how they can gather and generate online writing in a similar fashion to print.

SGABF: What crucial observations have you gathered from the self publishing scene in Singapore, from your various interactions across the art and design communities?

KP: Arguably, zines started from movements such as Dadaism. Then, practitioners would create posters and magazines to address topics of interest. Today in Singapore, there is too much focus on ‘lifestyle’ – at least commercially. Many self-published zines I’ve observed tend to touch more on what young adults really care about. Publications such as SAND Magazine, too, tend to bring out these themes. Having these voices is important.

I think there is a confusion as to what zines should be about. We see many people who just want to make a nice looking zine, but the content is lacking. That also reflects the state of the design scene in Singapore. A lot of it is about making nice posters and aesthetically driven objects, yet not enough thought is put into context or process.

I: I feel that some designers lack in-depth research, which ends up with them producing for the sake of production just to demonstrate something. That changes the perception of what exactly a self-published zine is about as opposed to the initial intention of the Fluxus movement.

KP: I think generally they lack an opinion or a strong belief. Of course they are very much influenced by successful magazines like Monocle. The idea of the zine, as a result, loses its way over time. I think designers like Atelier HOKO should be celebrated more. They are one of the rare few practitioners that look at things in-depth from a design perspective. Designers in Singapore tend to gloss over a lot of things.

I: Today, it seems that it’s not about disseminating information or content but challenging who makes the nicest zine or book. Consumerism doesn’t help when the people who buy are generally attracted to aesthetics. It’s a two-way street. At times, the audience controls what is being produced by artists and designers by way of their reception to certain publications.

SGABF: In terms of taste and appreciation for visual languages, do you think the audience and practitioners should be on the same page? Should the practitioner, then, be devising new approaches to navigate the audience’s perception of design and art?

KP: I think it is possible for practitioners and audience to be on the same level. Practitioners need to be more firm and rooted to their beliefs, carry out and address certain things in the way they know best.. A lot of times they are swayed by audience commentaries.

I: Or driven by numbers – in terms of sales or social media clout. That changes the direction of how independent publications are produced, even.

KP: The whole idea of numbers driving design is a pretty big thing. While I think there are certain advantages to it, there still needs to be a human driven decision-making process. That is not something that can be statistically proven. In Singapore, we tend to have an obsession with numbers that is consistent in different fields. We feel the constant need to be validated by numbers.

SGABF: Based on what we have discussed so far, how would you weigh the value of events such as Singapore Art Book Fair (SGABF)?

KP: I think such events are important to have. That said, I do think Singapore celebrates the festival culture quite excessively. These activities should still take place outside of large-scale formats and without the need for validation by numbers. I thought the addition of the pre-fair event ‘Deszinenation: Ground Zero’ before the fair dates in June by SGABF was really interesting. The exhibition wasn’t merely concerned about numbers but attempted to critically engage audiences.

Photo Credit: SGABF

I would love to see more individualistic actions happening within Singapore. At least in the art scene, there is an emergence of independently-run spaces. Students and artists are putting up their own shows. There are definitely more small-scale events popping up, and I would love to see that happening for design as well.

I: I think it is the nature of the business of design that does not allow for such practices. If you are a design studio like us that also explores art, that might change the language of communication. Design studios mainly operate on the business model of specialisation. If this change in focus can happen, it will switch up the entire scene.

SGABF: Numbers are used to determine how successful events, festivals and showcases are. Yet, it’s tricky to gauge how such initiatives are shifting perceptions. Some people think that outreach is important.

KP: It depends on the context. Reaching out is definitely a starting point. A lot of it depends on who is the initiator or parent is. When government agencies become the parents of initiatives, there is no real drive nor passion. I doubt there is any actual engagement with the audience. Small pockets of spaces and independent institutions, such as SGABF, engage with the people more intimately. This allows for real audiences to mature and carry out more constructive discussions. Exhibitions for entertainment’s sake rather than actual cultivation can be overwhelming.

Many designers in Singapore still think that design is a commercial activity, and fail to see the other aspects of design which could potentially take on other forms. That’s why the scene in Singapore is so different from neighbouring countries like Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. These areas have room for activities that don’t necessarily ask for a tangible outcome.

I: Adopting matured approaches to information consumption is important. Having independent initiatives such as SGABF would bridge a more in-depth level of functioning, rather than bringing about a surface-knowledge understanding of things. We need more events and showcases that allow for development and growth, regardless of scale.

A project of design studio Modular Unit, Supernormal is an independent art space that strives to present experimental and offbeat works and projects, ranging from design to artistic practices, and the in-betweens. The gallery is known for providing a creative and experimental platform emerging to established artists and designers in Singapore.

ZULKHAIRI ZULKIFLEE

Photo Credit: SGABF

SGABF: Hi Zul, firstly can you tell us more about your practice and how it has developed over the years?

ZULKHAIRI ZULKIFLEE (ZZ): My practice revolves around Malayness. In the recent years, I’ve been toying with the idea of revolving. We seem to place identity as a central aspect, and we’re all going in that direction. I find myself coming to a point of self-perpetuation where I don’t want to be talking about myself. When faced in this situation, I find that people have a difficult time entering the scenario.

Being Asians who are educated based on Western values, we don’t seem to have an issue understanding concepts or ideologies from these places. The contradiction lies in how people struggle to grasp the idea of Malayness. I’m not sure if I’m keen to define what makes anyone Malay which is also a long drawn conversation, rather than what ‘Malay’ can become. How can the Malay identity create space for other self-differentiating identities to enter?

The act of making space can be seen as a move taken when you may not understand where someone is coming from or what they are talking about. You make space to understand instead of passing judgement. I want to look at Malayness as creating a space for Malay people who may not identify with essential traits and at the same time exploring how other races may seek affinities with certain Malay attributes. That’s where the idea of knowledge production, social agency, distinction and taste come in.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

As an artist, I’m thinking of ways to communicate certain ideas from a visual standpoint. I’m not a cultural theorist nor a sociologist but I do borrow information from these fields to create a language that may bridge certain forms of understanding – especially when I’m working with dense text. How can we open up Malayness? It’s important to consider the works of other practitioners as well. I see the entire landscape as a form of collaboration where we should be listening instead of working in a silo. I have to be very attuned to other artists who are also working around the subject of Malayness. Sure, the works and ways of communication might be different but that’s what contributes to a dialogue. It should never be a monologue.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

Since we all have different worldviews, making sure that everyone can find affinities to an extent reduces the level of didacticism. That’s something I’ve been wanting to manifest with my own practice.

SGABF: Are you specifically working within the context of Singapore or are you also looking outwards to examine what Malayness means in other regions?

ZZ: When we speak about Malayness, we’re also thinking of the Nusantara (‘archipelago’) – the different Malay identities. People today are seeking their ethnic roots. We’re not just Malay – you could be Boyanese or Javanese, for example.

It’s strange because I’m Javanese but I don’t know anyone in Java. Perhaps if I looked deeper I might find someone with a connection. How can we speak of the Malay identity in the current times? How can I navigate through the everyday life, or as a Malay artist? I’m concerned with bringing the depths of my identity to the forefront, especially in a landscape where there are various majority groups. There’s also the process of understanding where your identity stands on a geographical scale. What happens if I ever step out of Singapore to pursue the arts? Will my work be less relevant?

SGABF: How did you come to create your art zine, Pisau dan Timun (Knife and Cucumber)? Are you ever concerned by the shifts in context as the zine travels to places such as New York and Chicago, in a country that’s so polarised?

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

ZZ: The zine was created from an open call by local risograph press, Knuckles & Notch. They eventually brought the zine to New York Art Book Fair, and it was there that the School of the Art Institute of Chicago purchased a copy and catalogued it in their library.

My approach of making the zine stemmed from a desire to look at mat reps (a group regularly seen as delinquents). At that point in time, I wondered why wasn’t anyone seeing them as a subcultural movement or group. Why were their idiosyncrasies not celebrated? We are familiar with more obvious groups like the punks and skinheads but I was particularly interested in the possibilities of a subculture that exists on a day to day. Readers in the States had no issues referring to the subject matter as a subcultural group.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

More importantly, the zine was a creative outlet for me. The images were all taken from the Internet, and rearranged from a visual standpoint of communicating the idea of a marginalised or subcultural group. At the same time, I had to be aware that I couldn’t just use these terms loosely. That’s why it’s important to seek affinities from worldviews. I may be creating something with an impetus of talking about a Malay working class, but a person of a different background may find other meanings or interests within it.

There might be some subcultural interests that perhaps vary from my intention but it makes the work more resistant to closure. I’ve become very open to accepting that side of art making and consumption.

SGABF: Are people necessarily sensitive to local subcultures, in terms of identifying them?

ZZ: If we’re talking about mat reps, it seems that some people don’t really know it exists. It depends on your class or background, perhaps even the school that you went to. I can pick out another Singaporean who’s not Malay and ask them about mat reps. There’s a chance someone might find the term familiar but can’t be entirely sure or even not know it at all.

SGABF: Can these expressions and examinations be made more accessible, and how necessary is it to do so?

ZZ: Well, first of all, I don’t identify as a mat rep. So I don’t see my work as an attempt to represent this group of people. They clearly don’t need it either. I just thought it was a good topic to analyse creatively. There’s no harm making these things more accessible but it’s important to remain authentic about my intentions, and acknowledge the fact that I’m creating a type of semiotic analysis as someone who doesn’t have access to this community even though I’m Malay. Can you just imagine the people who are even further away from me?

I cannot pretend to represent every single Malay household or individual in Singapore. The upper class, for example, may not reveal themselves for us to comprehend. In that sense, even if I were to create some sense of accessibility, it would just be one segment of a rather plural understanding of one group.

SGABF: How would you weigh the maturity of cultural and identity studies and examinations among our society?

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

ZZ: We are definitely doing way better today. What’s interesting is that we see a wave of people who are comfortable with talking about their identities, and to be able to speak from their worldviews and understanding of what a Malay group could be. For me, most of the time it boils down to a sense of comfort where I don’t have to visibly declare the ‘Malayness’ in my work.

At the same time, I suppose some people don’t want to talk about it so as not to limit themselves. There’s this constant fear of pigeonholing when we take positions. Most of the time, we refuse to stay put for fear of missing out. Personally, I like the notion of straddling. I don’t find myself pigeonholed even though my practice is focused on Malayness. Perhaps it’s a mental projection. If you think that you’re being limited then you’ll inadvertently see it that way.

It’s interesting when we view it from a binary perspective. When we set up an exhibition or a showcase that involves alternative spaces or works, that doesn’t mean that we don’t want to be represented by galleries. It’s not always anti-establishment or oppositional. I see it more as being generative. I’ll function differently if you give me a space that’s not a white cube. Similarly, I’ll understand and respond to the structure of a white cube space when presented with the opportunity.

SGABF: As a curator, how purposeful is your selection process in response to the space?

ZZ: I’m usually into the idea of working in unfamiliar spaces because I find certain limitations to be very productive. When looking out for artists or works, the ones that possess a strong visual presence stand out to me. Also, the artist needs to know what they are doing. I’ll always observe if they have great work ethics as a person. Time is also a key factor. It’s usually reasonable to give artists three to four months to create a work. With the shows that I set up, the lead time may be as little as four weeks. It’s stressful but I think there’s also a sense of excitement in trying to make the limitation work.

Whatever that I ride or put forward as a curator is either a response to a current or specific moment with urgent concerns. I don’t see it as a curated show but rather a curatorial proposition. It’s not just about staging a work but how we can talk about certain ideas with a major significance.

SGABF: What are the possibilities of translating these spatial and visual experiences into a publication format such as a zine, art book or monograph?

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

ZZ: For one of the shows that I organised with Nhawfal Jumaat, RUANG, which happened at Joo Chiat, we did produce a catalogue or publication of sorts. I worked with a graphic designer based in Indonesia. During the process, I didn’t see him as just someone to respond to our brief. We saw him as an artist and creative as well. The way the book was made traced the idea of how we could capture the moment and rawness of the space on paper.

SGABF: Do you see publications as tools likely to help develop your practice in a completely autonomous way?

ZZ: Zines and art books are autonomous. However, I don’t wish to mystify or romanticise the idea of books. I believe that reach is important if you’re thinking of disseminating information. Because of that, autonomy is never fully accomplished. If your purpose is to reach out to people, what is really achieved if it doesn’t travel along a circuit?

The discussion of autonomy is similar to the idea of ‘alternative’. Sometimes, radicality isn’t as simple or even necessary. What we do understand from these words? You can never represent something fully. Sure, we can limit certain practices that aren’t ideal and place our own agency but things are liable to shift with the dialogues that are created – at least in a setting where reach is desired.

SGABF: Can you recommend up to three art books and/or zines you’ve read or collected that might have informed your artistic beliefs today?

ZZ: Conference of the Cockroaches - The most despised and the least understood by Zaki Razak, Blnd: The age of darkness & darkness of being 2003 - 2013 by Zaki Razak, In Love by Norah Lea

Zulkhairi Zulkiflee is a visual artist, educator and exhibition-maker based in Singapore. His practice explores the notion of Malayness in relation to knowledge production, the social agency and distinction/ taste.

He has exhibited in several group exhibitions and organised alternative group exhibitions like Malais-A-Trois(2018), LUCKY show (2018), RAID (2018), RUANG (2017) and Dancing on the Spot (2016), tapping on off-kilter locations like an air raid shelter, a vacant shophouse, and a metalworking building.

The beginnings of the zine is commonly associated with the 1920s. Then, artistic and philosophical movements like Surrealism published small runs of print material – most typically characterised by collage and bricolage as forms of expression. It is believed that zines became a distinct form in the 1930s when science fiction fans began to publish and exchange stories (‘fanzines’). In the 1970s, punk zines came to the forefront as a way to publicise underground shows that were being sidelined by established music press outlets.

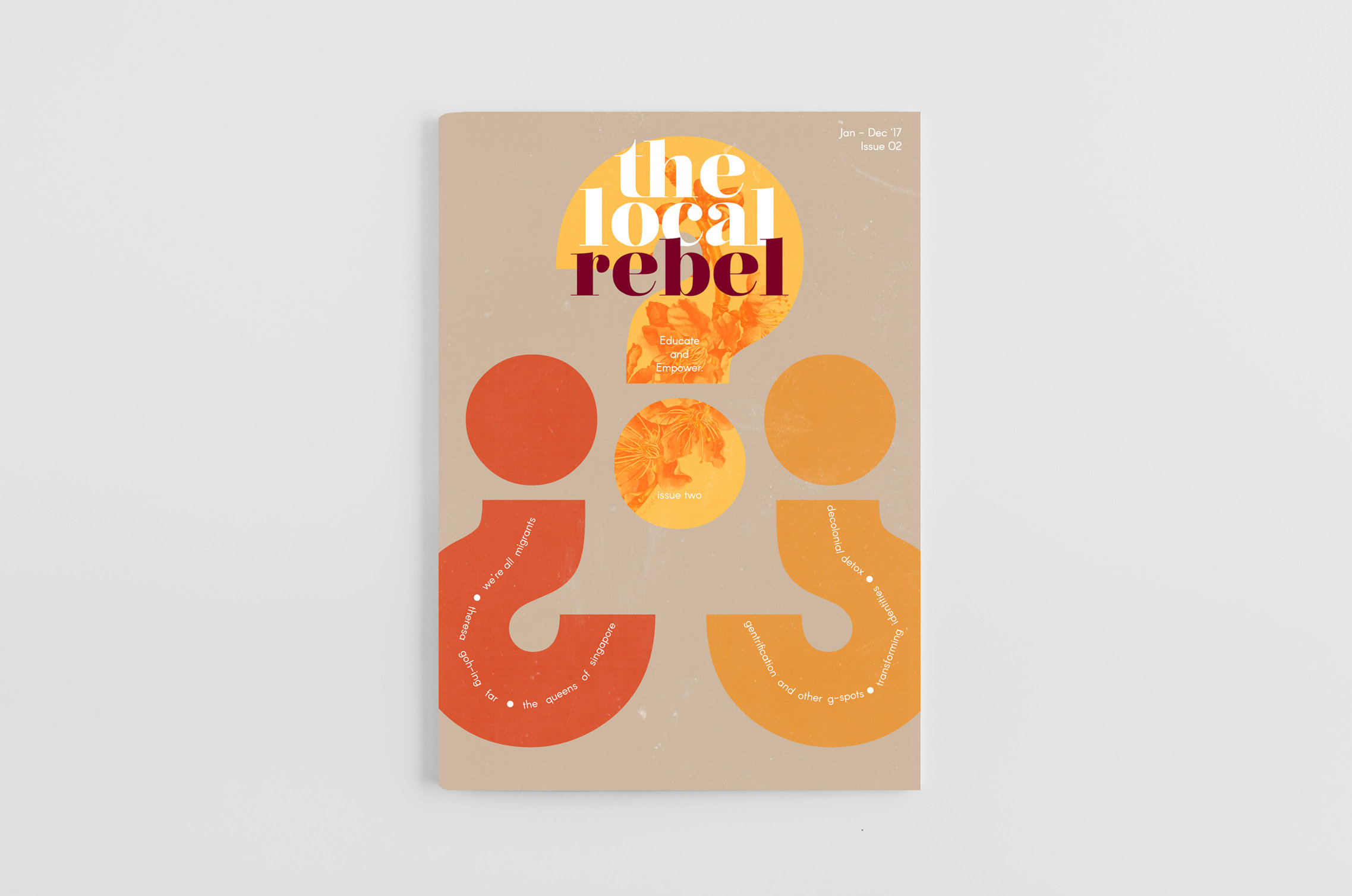

Common associations with the zine include the 90s Riot Grrrl movement, which encouraged a new wave of personal and activist content. Likewise in Singapore today, intersectional feminist collective, The Local Rebel, creates zines that address gender equality for youths. Through open calls, the collective gathers contributors who handle visual and written content for each issue.

Image Credit: Courtesy of The Local Rebel

In the past, young artists used zines as a way to break out of the gallery exhibition white cube format. Similarly today, local collective no ceiling paper wall, adopted the format of a zine in their process of reimagining alternative spaces and ways of presenting artworks in 2018. “A huge challenge was piecing together the video projections and translating the experience from a physical space to the pages of a zine. The format was ultimately chosen because we wanted to reach out to a wider demographic instead of keeping the works contained within a section space. For us, it was also about breaking out of terminologies too.”

Image Credit: SGABF

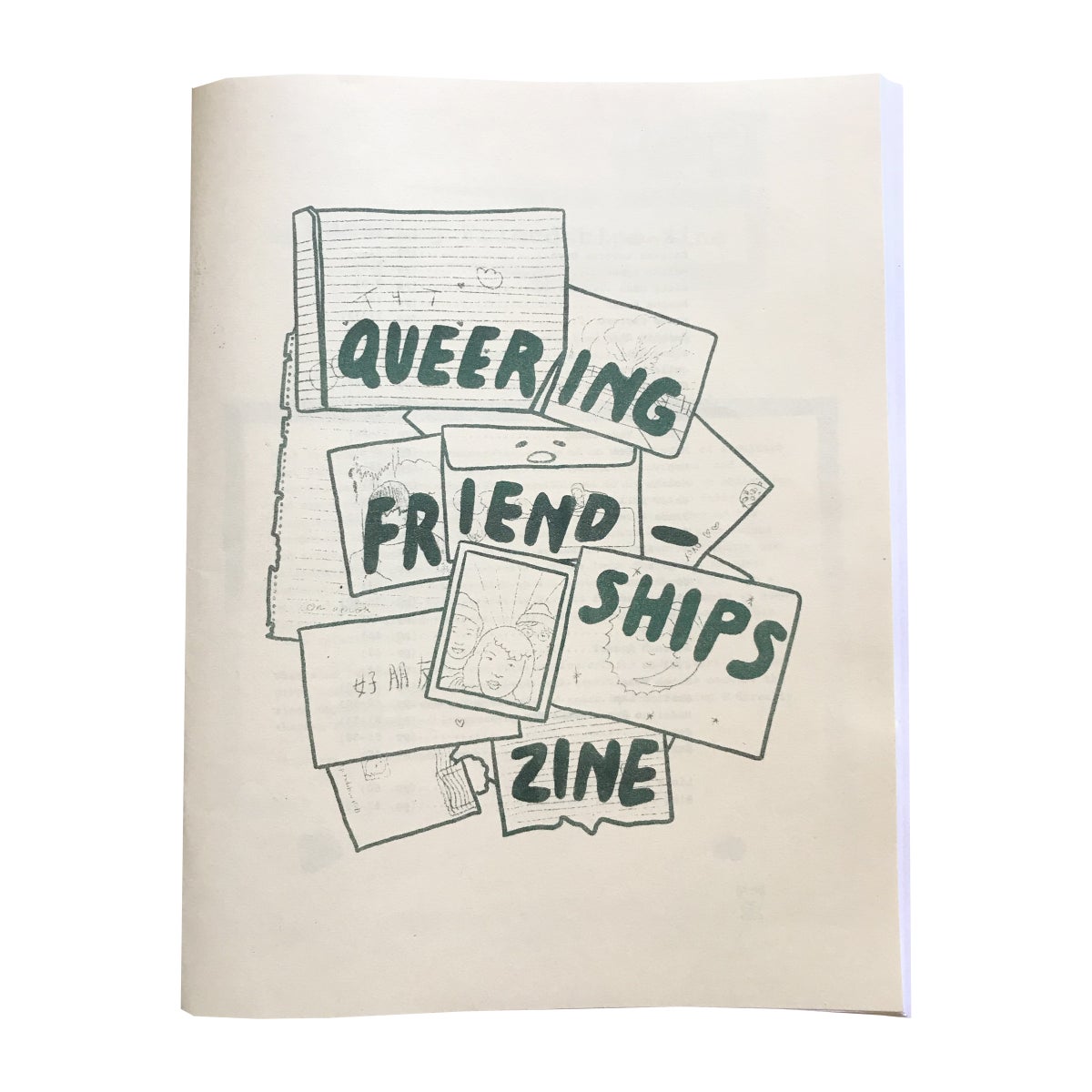

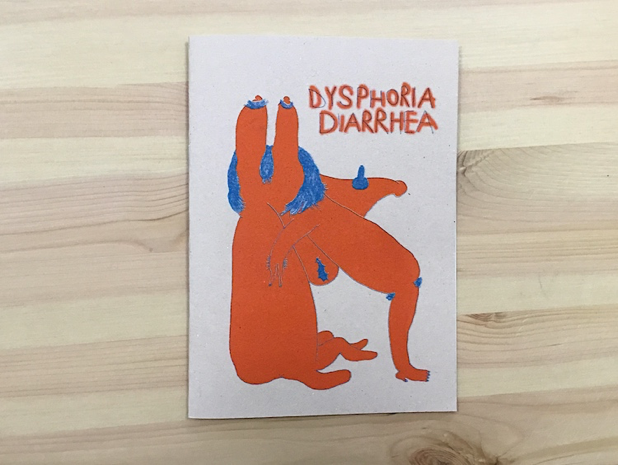

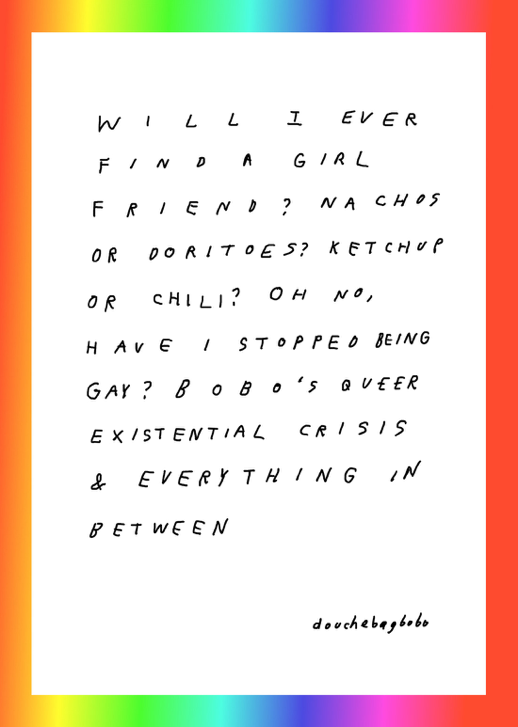

How a society shapes socio-political consciousness can be examined alongside the resurgence of zines in each particular generation. Each time, makers are encouraged to look towards more options to explore zines created based on the perspectives of various cultural backgrounds, lifestyles and myriad of influences. A street library along Little India filled with controversial zines, the Zine Library by local collective Squelch Zines and Singapore’s first Queer Zinefest (QZF) started in 2018 are part of a new wave of zines local audiences have experienced.

Image Credit: Queer Zinefest

In the early stages of QZF, Gabbi Wenyi Ayane pooled resources from experienced makers and organisers in Singapore. She first brought the idea to poet and comedian Stephanie Dogfoot who introduced Malaysian zine distributors that expanded the initiative in the region. She also roped in fellow artist and illustrator Joy Ho, who designed the event visuals and assisted with the running of the festival. To ensure that QZF responds to audiences effectively, Gabbi brought in arts manager Akansha Aether into the team. This mix of backgrounds within the organising committee has made the first edition of the festival and its year-round workshops more diverse and free.

The culture of zines looks beyond the product. Instead, we are taught to explore ways to create safe spaces for makers to express and share their ideas. As Akansha described, “We wanted everyone to have a good time, not just look at the zines. We wanted them to stay, have good food, learn about the community through other workshops, and bring people together with music.”

Image Credit: Queer Zinefest

In the age of capitalism, economic numbers are often the only measure of value and success, especially when long term sustainability is the goal. This leaves little room to exploration for small groups, usually with little to no organisational support, such as QZF. What Gabbi and her team had to consider was the number of community members. “In comparison to other events, we had a much smaller volume of zine makers which forced us to think of other things that people can do. Ultimately, it’s still a community that we are growing here,” she explained.

As we develop the local zine culture, it is important to understand the past challenges faced by predecessors. The first idea of local zines sparked from a lack of uncensored publications in Singapore. You couldn’t turn to state-owned magazines and expect full disclosure on concerns such as the realities of middle class families, people who were coming to terms with their identity and inter-racial experiences. Even consumption of music, books and films could be too sterile if one depended too much on the ratings and listings on mainstream and family-friendly channels. One solution was pop culture magazine BigO, arguably one of the most prized possessions of the Singapore landscape.

As Jasmine Ng, Associate Producer of Shirkers and filmmaker puts it, “you could say that [BigO] was Singapore’s first ever alternative indie-culture zine. It started in that photostated glory days where everything was kind of cut and paste. These were the pre-internet days so things were a lot harder to search out. But the thing about the culture of zines was that you could trade or order. They came to you easily enough.”

Imagine this scenario – meeting Phillip Cheah, one of the most important figures in the Singapore film scene as a young filmmaker. Having created Before I Get Old (BigO) with his brothers and friends, after a line from a Patti Smith cover of ‘My Generation’ which said, hope I die before I get old.

“We were there as 14-year-olds and wanted to be part of it. All these people had in-depth access to comic books and music that I have never heard of. It was a treasure cove. I was also introduced to all kinds of music and movies articulated from a local perspective. Yet, it was very much this boy’s gang and we didn’t know how to fit in,” Jasmine recounted.

Image Credit: Courtesy of TODAY

In the backdrop of political unrest in the 60s and 70s, the 80s and 90s saw the introduction of several stringent regulations to curb noise. This made the zine an even more powerful and democratic medium. “Anybody could do anything and make anything their subject, from a guy making a comic zine about working in the old folks home to a particular obsession with a music genre. That was very eye-opening, especially coming from a place like Singapore,” Jasmine explained.

The counterculture spirit of zines has certainly evolved with shifts in media governance, public perceptions and approaches to socio-political issues. As Joy (QZF) pointed out, “I think a large part of the reason why we can say zines look ‘less political’ now is because we can openly express our beliefs today. How much access zines give and its transformations are a reflection of how we react to culture.”

Photo Credit: SGABF /Deszinenation: Ground Zero (Exhibition)

For an object as politically weighted as the zine, how telling is its resurgence across generations? Members of collective, Squelch Zines, seem to resonate with the zine experience with our current climate. “Zines are a reflection of the mindset of society, particularly in the perspective of the artists who create them. The objective of a zine has never changed – it has always been and will continue to be a medium for communication. That is its core purpose,” they explained.

That said, it can be argued that the idea of liberation today is no longer associated with the politicalness of subjects. Moving beyond the political themes of zine making, then, could be seen as a more open approach to sharing ideas. This argument in itself is highly debatable, like how zine culture has progressed. What could be considered as ‘under the radar’ in the 80s and 90s might be vastly different in the present context. What does it say about our zine culture when we reference productions like BigO while encouraging more makers to ‘return’ to the advent of cost-effective publishing with photocopy machines?

Image Credit: SGABF /Collection of Squelch Zines

The openness of the zine brings about greater cultural participation. A medium for youths to claim their place in society, especially those who find themselves on the margins of power. It reaffirms the strength of communication. As no ceiling paper wall mentioned, “anyone can make a zine, which is really flexible. The zine culture pushes a form of unified and harmonious activity. Things like stepping into a bookshop and discovering where to get the best pizza in town from a zine or getting an anarchist to write an essay. You can read a zine anywhere, too. Formalities and structure can be intimidating, and the fluidity of zines help people get over that.”

To fully understand the underbelly of Singaporean culture through zines, we should look towards unobserved communities that would undoubtedly piece a more comprehensive and inclusive explication of the belief systems present in our society.

Photo Credit: H55

HANSON HO (HH): Prior to that I hadn't really worked for anyone for very long. At that point, I was quite desperate to come out and be independent, not creatively but financially independent. I saw a dead end coming my way in the long run so I felt that the only way to propel myself and to accelerate my growth was really to set up my own studio. At the time I found that my predecessors in the industry were quite boring in the way they were being run. They were mostly brand consultants or publications designers who designed things like annual reports or newsletters whereas our counterparts in the West or even in Japan were doing a lot of things that were carrying independent voices — where their individualities were allowed to be expressed in their clients' works. I thought that this should be the way to go and since I couldn't win my predecessors, I had to change the game. So if I wanted to come out on my own, I had to do something that is more individualistic, rather than just follow the ways of operation which were already established in the past.

I operate in a less hierarchical manner. The studio is fairly small and for many years, I rented it on my own and my clients from a very niche market found it refreshing because they are meeting the creative, the owner, and also the accounts manager — all in one. In a way that’s what architects have been doing. To me, that's beneficial to the work rather than having too many people which might lead to miscommunication and also, having to bear the higher costs with a bigger team. So, the process is less formal because it’s less hierarchical. The relationship that I have with my clients is more friendship-based. With this, my work becomes more individualistic and more expressive.

Some say the studio has a house-style, which is something that was not allowed previously. The mindset was that designers should have different ideas and styles to cater to different clients. But for H55, we have a fundamental belief and approach, and clients come to us for that.

SGABF: You’ve run H55 independently since 1999. Why did you choose to stay independent after all these years?

HANSON HO (HH): Prior to that I hadn't really worked for anyone for very long. At that point, I was quite desperate to come out and be independent, not creatively but financially independent. I saw a dead end coming my way in the long run so I felt that the only way to propel myself and to accelerate my growth was really to set up my own studio. At the time I found that my predecessors in the industry were quite boring in the way they were being run. They were mostly brand consultants or publications designers who designed things like annual reports or newsletters whereas our counterparts in the West or even in Japan were doing a lot of things that were carrying independent voices — where their individualities were allowed to be expressed in their clients' works. I thought that this should be the way to go and since I couldn't win my predecessors, I had to change the game. So if I wanted to come out on my own, I had to do something that is more individualistic, rather than just follow the ways of operation which were already established in the past.

I operate in a less hierarchical manner. The studio is fairly small and for many years, I rented it on my own and my clients from a very niche market found it refreshing because they are meeting the creative, the owner, and also the accounts manager — all in one. In a way that’s what architects have been doing. To me, that's beneficial to the work rather than having too many people which might lead to miscommunication and also, having to bear the higher costs with a bigger team. So, the process is less formal because it’s less hierarchical. The relationship that I have with my clients is more friendship-based. With this, my work becomes more individualistic and more expressive.

Some say the studio has a house-style, which is something that was not allowed previously. The mindset was that designers should have different ideas and styles to cater to different clients. But for H55, we have a fundamental belief and approach, and clients come to us for that.

Graphic designers

don't generally have a style, they listen to what the clients want. For us, it's different. Our work, by and large, has a spectrum of look and feel, and a way of thinking. The clients then come to us for that, and not the other way around.

In terms of ownership, it is still independently-owned and of course, that makes a lot of things easier in terms of the culture and decision-making. I basically have full control of the creative direction and finances. For me, that control is very important. It allows me to steer in different directions, whenever needed. There is more freedom, and when there is more freedom, the work becomes more creative.

![]()

Photo Credit: H55

HH: We definitely need to cater to the collaborators' needs when we are working with someone but, by and large, the way of managing a project is the same for me. It's to identify and be extremely clear about the perimeters and limitations of the project and then brief the artists, designers, or myself to try and satisfy a number of checkboxes. It may sound very uncreative, but that's where the real creativity lies. Many designers or creatives say that a project cannot turn out well because of these limitations — money, space, etc. — but there are always escape routes and if you can find the escape route to every project, then all your projects will be portfolio material, works that you are proud to show rather than feel ashamed of.

I think it's about ignoring how people think it should be done. It helps to look at examples of good work or works that are good but not entirely relevant. For example, if you're designing a novel, it doesn't mean you can only refer to novels. You can look at magazines, posters, or even contemporary art, maybe that can inform the design. It is important that you don't have all these preconceived ideas, and you're not afraid or think that just because the client thinks a certain way, you have to do things differently. You can incorporate some of the client's thinking while showing them what other things are possible.

In terms of ownership, it is still independently-owned and of course, that makes a lot of things easier in terms of the culture and decision-making. I basically have full control of the creative direction and finances. For me, that control is very important. It allows me to steer in different directions, whenever needed. There is more freedom, and when there is more freedom, the work becomes more creative.

Photo Credit: H55

SGABF: You spearheaded and curated many projects, including LTA’s Art-in-Transit Programme for the Downtown Line. Do you find that your approach differs when it comes to showcasing art on different platforms – from Biennales, gallery shows, to public spaces?

HH: We definitely need to cater to the collaborators' needs when we are working with someone but, by and large, the way of managing a project is the same for me. It's to identify and be extremely clear about the perimeters and limitations of the project and then brief the artists, designers, or myself to try and satisfy a number of checkboxes. It may sound very uncreative, but that's where the real creativity lies. Many designers or creatives say that a project cannot turn out well because of these limitations — money, space, etc. — but there are always escape routes and if you can find the escape route to every project, then all your projects will be portfolio material, works that you are proud to show rather than feel ashamed of.

I think it's about ignoring how people think it should be done. It helps to look at examples of good work or works that are good but not entirely relevant. For example, if you're designing a novel, it doesn't mean you can only refer to novels. You can look at magazines, posters, or even contemporary art, maybe that can inform the design. It is important that you don't have all these preconceived ideas, and you're not afraid or think that just because the client thinks a certain way, you have to do things differently. You can incorporate some of the client's thinking while showing them what other things are possible.

SGABF: What do you think is the current climate of Singapore’s design, and where do you see it going in the next 10 years?

HH: There are definitely more younger designers and smaller studios that have sprouted in the last five to ten years, but still not very many. When I first started out in 1999, I was probably the only one. Thankfully I also had peers like Asylum and Kinetic who did the same thing, which I think is a significant movement. It was encouraging for each one of us; to see each of us doing something different but interesting. Right now I would say we're at the low point of the wave, where the scene is pretty slow and stagnant in some ways and will continue to be like that for awhile.

I try to create a map for myself and my work; where it's going in 20 to 30 years' time. As I continue to map my way into the future, thinking of what I do, I explore deeper into the craft. The works need to become better and more significant. My interest from the beginning was always to intervene with the culture in Singapore. Which means that I need to engage with the correct types of clients and audience so that my work, books, logos or brands stay and survive as part of the visual culture around us. They should become monumental as time passes, and not get thrown into dustbins like brochures. I hope to create these epitomes of things so that when I reach a certain old age, they will all be floating around Singapore and other parts of the world where people can find and enjoy.

Photo Credit: H55

Photo Credit: H55

SGABF: How do you perceive the cultural impact design has on a place and society like Singapore?

HH: I don’t really like to proclaim that design can have a big cultural impact. It will definitely have some sort of impact but I don’t think it will "save the world". However, I think what’s more important is the acknowledgement that design is important, that design thinking is important and that having good taste is important — good taste in a broader context, not just dressing well and looking fashionable but having a healthy mindset that imagination, creativity and diversity as a way of life is important.

Design has undoubtedly influenced Singapore. I mean, everybody has become more image-savvy because of mobile devices, globalisation, access to all kinds of media and magazines, and different brands that have landed in Singapore. Singaporeans appreciate design a lot more now than when I first started. They do see the relevance of design, and that it’s not something that is frivolous.

![]()

Photo Credit: H55

HH: Hopefully it will be, in a way, disruptive to how they would normally think about things and also to realise the importance of publishing. I hope the younger generation don't see art books as a kind of sentimental object because in a digital age, people see print, polaroids, photography, film photography, vinyls, as a nostalgic, sentimental thing. Hopefully, they see it as processes or a means that can help them to not just generate new ideas but question things that they always thought were a certain way; to disrupt the way they think and to see publishing as a kind of validation to self-existence. Because ultimately that's why people publish. It's not a sentimental thing like keeping a diary or a scrapbook, it's more than that. It is to validate that they are different. Whether you're publishing something into a book or on a website doesn't matter. We have to embrace diverse viewpoints and this can be expressed through publishing so that you can share these ideas with people.

H55 is an award-winning Singapore-based design and communication consultancy with a reputation for conceiving relevant, engaging and effective ideas. Since its establishment in 1999, H55 has been independently owned by award-winning creative director Hanson Ho, who continues his hands-on attitude towards design and project management. Till this day, H55 remains as a light and compact office so as to be creatively sustainable, focused and dedicated to a select range of clients. H55 has worked with a variety of clients ranging from government ministries, museums, public-listed companies, small-to-medium-sized enterprises, new startups and individuals.

Photo Credit: H55

SGABF: Finally, SGABF2018 aims to provide a space for artists, designers, creatives, and consumers to think critically about art — in its various forms and formats. When it comes to critical thinking, what sort of questions or ideas do you hope people will hold in minds when engaging in a festival like that?