A collection of conversations with a diverse range of local and regional creatives

Library Conversations for SGABF2020

We examined the systems that support art book making and independent art book publishing in Singapore and the region.

A Closer Look for SGABF2019

We gathered perspectives on our zine and art book culture, and discuss the possibilities of self-publishing today.

21 Creatives for SGABF2018

We sat down with 21 creatives of various disciplines to learn about their practice and asked each of them to fill up a blank page in a notebook.

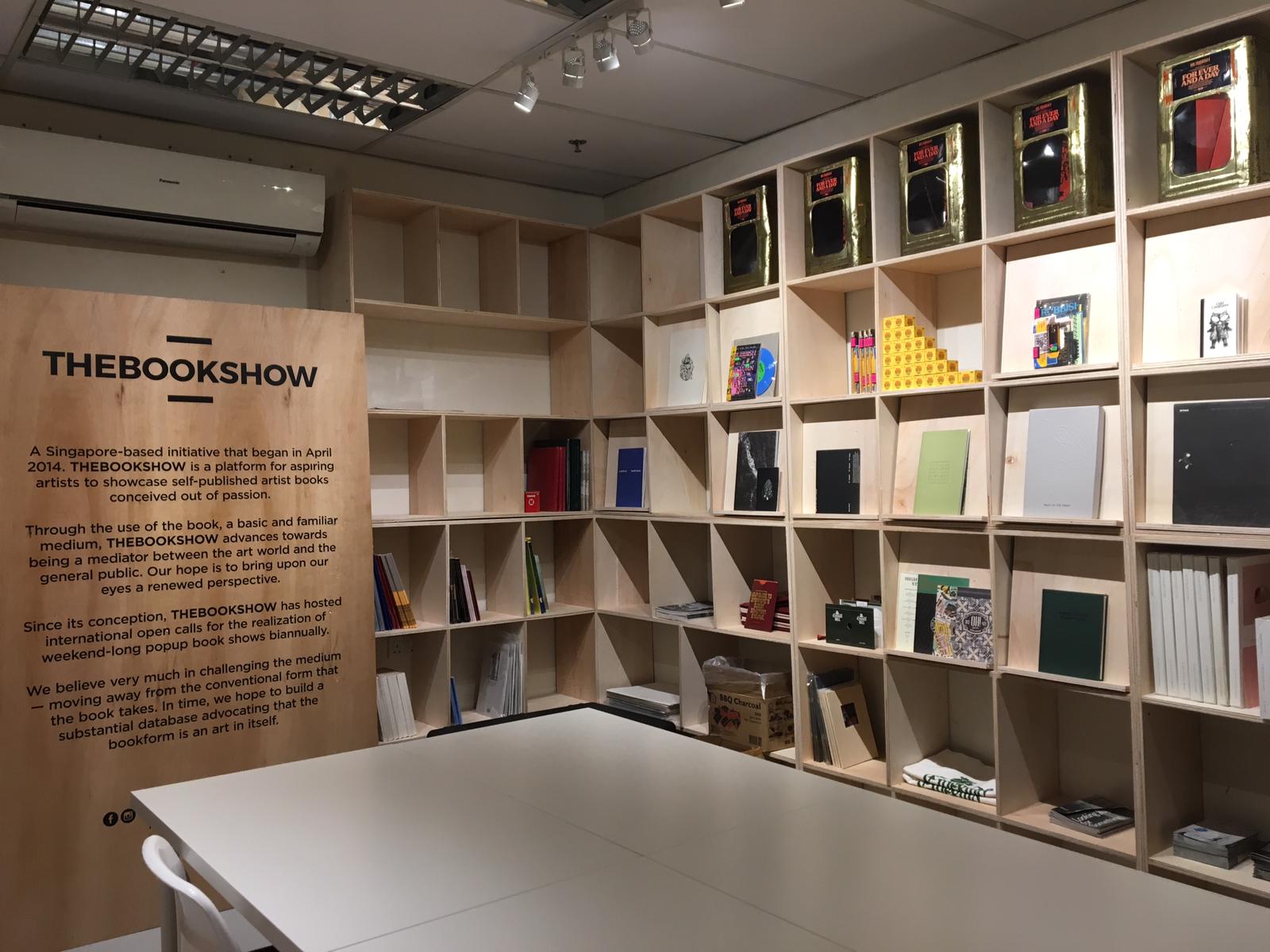

Queer Reads Library and Queer Zine Fest

Photo Credit: Queering Friendships by Mixed Rice Zines

Photo Credit: Queering Friendships by Mixed Rice ZinesOBJECT LESSONS SPACE (C): Hi Queer Reads Library and Queer Zinefest! Our first question for both teams relates to the zines that were selected for our conversation. It was clear that the zines that were chosen are near and dear to the hearts of both teams. Could you both tell us a little bit as to how you picked these zines out, and how your own personal connection with zines began?

Queer Reads Library (QRL): When Beatrix and Kaitlin were co-founding QRL, Beatrix connected the library to Unity Press from Oakland, California. Through Unity, we were introduced to the Taiwanese-American artist J. Wu who creates compilation zines under the title Mixed Rice Zines. Kaitlin connected with J over email in 2018 during QRL’s first pop-up, and one year later they met IRL in Taipei. Kaitlin and J felt instant friend chemistry, and J started brainstorming their next collaborative zine with the theme Queering Friendships, on finding love and intimacy outside heteronormative/romantic norms. The zine features over thirty contributors, mainly queer/trans and Asian identified. It feels fitting that this zine about friendship is laced through with personal connections: the mutual support between Beatrix and Jeffrey, Jeffrey and J, J and Kaitlin, and all the contributors who sent in their photos of friends, friend-love letters, poems, drawings and texts.

As for the back issues of Horizons, the publication is named after a support hotline that is currently led by Reggie Ho (also founder of LGBTQI+ nonprofit Pink Alliance). Founded in February 1992, Horizons hotline is one of Hong Kong’s oldest queer support organisations, and has three call lines in Cantonese and English. Ho joined as a volunteer in 1998. Their publication Horizons is described as “Hong Kong’s comprehensive resource on lesbian & gay counselling since 1992". It contains bi-lingual coverage of queer meet-up spots, letters to the editor, event/party/parade listings, and resource lists. The design is eye-catching and playful, with collage elements and bright spot colors (lime green, egg yolk yellow) that celebrate a queer sensibility alongside important information.

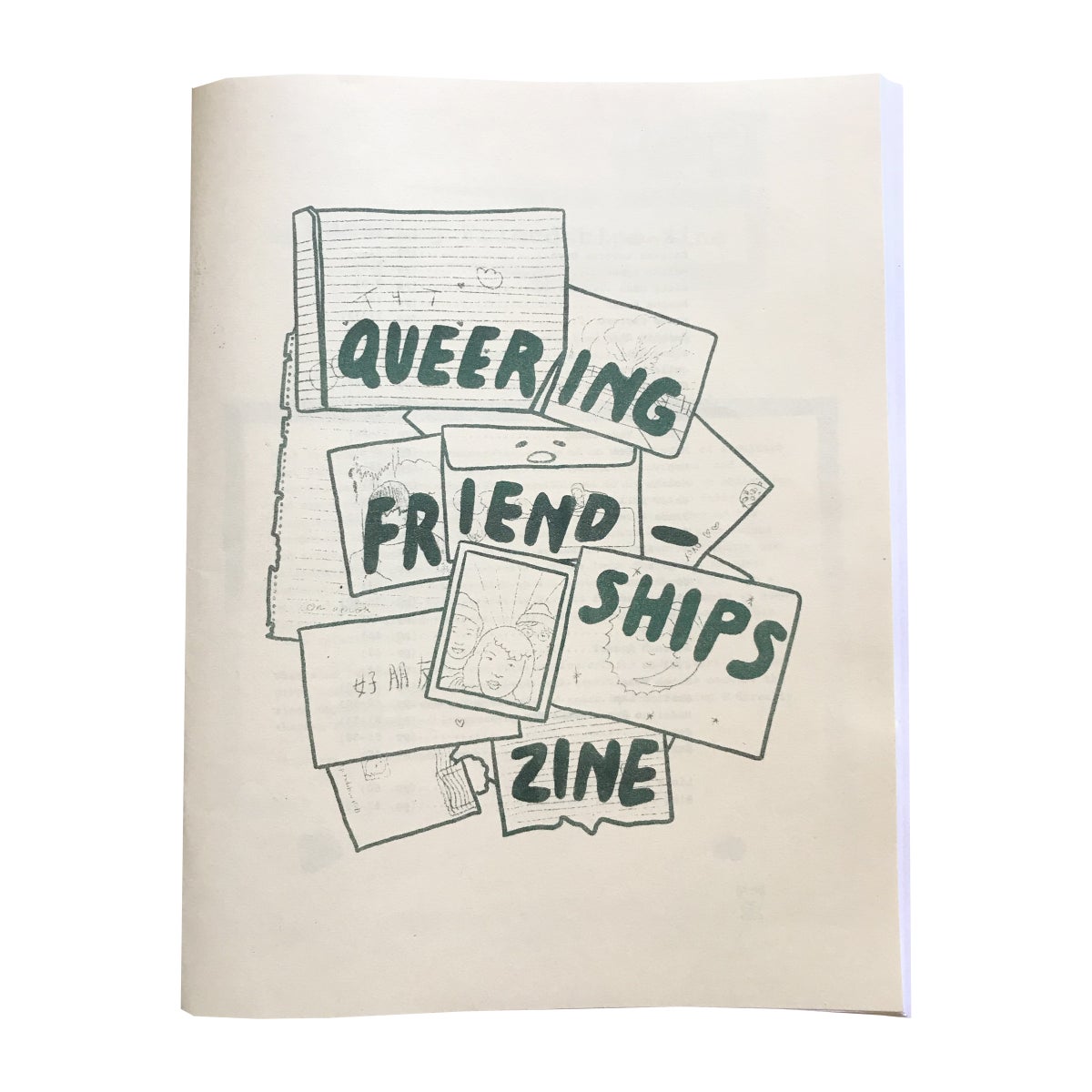

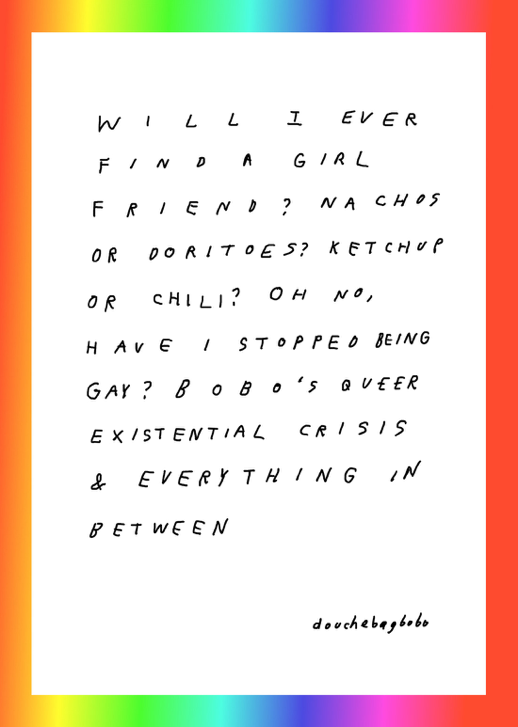

Queer Zine Fest (QZF): We picked zines that are by Queer zinesters in Singapore! There are so many good local LGBTQIA+ creators making punk zines, chapbooks, art zines, political zines… (and you can find lots of them through us!) but we finally managed to narrow it down to two that we're personally enjoying a lot right now. Aki's zine is so comfortingly confessional and warm. Especially now that lots of us Queers are disconnected from our LGBTQIA+ families or stuck with less-accepting housemates, Dysphoria Diarrhoea is a knowing smile and an empathetic corner to sprawl out in. As for Esther’s currently untitled zine, her expressive linework and text read as a heartfelt memento to those who are still figuring out who they are. A stream of consciousness approach to crushes and “queer existential crises”– like a letter to a younger self that someone else had penned.

Image courtesy of Esther (she/her)

QZF: The team all came to zines at different points in our lives and for different reasons, but we're all united in our belief that zines can be a super powerful resource and healing force for Queer people! Zines are so radical as a totally uncensored, personalised medium in a country where everything is heavily censored and commercialised.

OLS: Zines have always been an alternative and important source of information, and often function as community noticeboards, disseminating information and educating readers. Horizons was one such resource, and was incredibly important for queer community in the 90s. Could you tell us about the significance of having these back issues in your collection, especially considering their historical significance.

Photo Credit: Horizons issue 32, 1998

QRL: QRL has been incredibly privileged to befriend longstanding members of the LGBTQ+ community in Hong Kong, including activist Connie Chan and designer Po Hung. It is through these connections that we are able to access printed matter produced by the HK queer community in the 1990s. In fact, Po Hung— the Horizons newsletter designer— donated these back issues to our library. Having queer vintage titles in our collection reminds us that the work we’re doing as a library and community space is a continuation of the work that’s been done by queer folks before us. Since the founding of QRL in 2018, we’ve had the opportunity to foster intergenerational connections with queer folks of all ages, and we cherish these connections deeply. For example, back in May 2019, we had the chance to meet with an intergenerational group of queer folks for our Queer Lexicon workshop to discuss the various terms used by our community throughout the years in HK.

OLS: Something that struck me whilst looking through the zines that your team picked out was that they both use the zine, illustrations and emotive text to work through complex feelings. As organisers and creatives yourselves, has it been important for your team to work alongside and collaboratively with zine-makers who lean into and embrace the zine’s material and affective quality?

Photo Credits: Sayoni x QZF at The Moon, 2019

QZF: Absolutely! Although we suppose that pretty much all zinesters embrace the zine’s intuitiveness and emotion – you must really feel for something to get down and create it all on your own. There’s a certain immediacy to the medium, a certain urgency in the way we curl together and produce small quantities of things very close to our hearts, and I think that kind of blurry-eyed euphoria is at the heart of what QZF does. The zinesters we’ve met through its two year lifespan have really shaped the way we see zines as a whole, and I think each and every person we’ve worked with has also left a deep, wonderful footprint on our own paths as artists, organisers and human beings.

OLS: The importance of safe and affirming queer spaces cannot be over-emphasised, and this is something that both Queer Reads Library and Queer Zine Fest have worked towards through the establishment of physical presence in terms of a library and a festival respectively. Having said that, both initiatives take a slightly more transient approach with regard to a permanent venue.

Could both teams speak a little bit more as to whether the format of the zine (in terms of DIY/punk culture or ease of distribution) influenced this peripatetic approach, and how this fluidity has shaped your understanding of what or where a safe space can be.

QRL at Booked Art Book Fair Hong Kong 2019, Image courtesy of QRL

QRL: The DIY nature of zinemaking and self-publishing frees us to imagine a library beyond a set location. In particular, the challenges of nurturing and building queer-positive and intersectional spaces in Hong Kong is amplified by high rental/operation costs and the acceleration of capitalism. We combat the notion that the library must have a fixed location by celebrating our malleability to pop-up wherever we may be, if that happens to be Vancouver, Taipei, or Singapore. By curating selections for specific audiences, the library is responsive to its various audiences across different geographies. A safer space looks like where we can add to and be part of existing conversations and communities, rather than just parachute in. We aim to listen and learn, and are grateful for the privilege to be welcomed into people’s homes, DIY spaces, and book fairs.

QRL at HK Queer Literary & Cultural Festival 2019, Image courtesy of QRL

QZF: Yeah – a zine itself is so definitely a safe space. A portable brave space! A space just for you, which you can share or not share as you like. Nobody can come into your zine! Nobody can intrude on your space. That’s one of the reasons it’s so powerful as a space/tool for Queer people, especially in Singapore where there really aren’t a lot of physical spaces you can be loud and Queer and brutally feel things.

QUEERSTMAS at soft/WALL/studs, 2018

We didn’t want a permanent venue because we like the idea of highlighting a new LGBTQIA+ friendly space every time we bring people together. Queer spaces in Singapore are few and far between – we’re mostly relegated to the nightlife. It’s been really exciting to encounter all these places that exist right under our noses that are actually really welcoming and loving. We worked with Camp Kilo in 2018, and The Moon, BUNKERBUNKER!! and soft/WALL/studs in 2019. All of these are spaces that are accessible to under-eighteens and people who may not want to be in a space where there’s dancing and loud music and drinking.

Queer ZineFest SG at Camp Kilo Charcoal Club, 2018

That approach has been kind of altered by COVID-19, because physical spaces are no longer an option for a lot of people. These few months have shifted our focus to the ways online planes can become brave spaces too. It’s not a new phenomenon – the Internet has always been an alcove for young Queer people! But I guess we’re learning how as organisations, we can be involved in building that safety net without intruding on the webs people have already built for themselves. For us, that looked like creating a Discord channel for LGBTQIA+ people in Singapore, and running Pajama Parties on Instagram Live during the CircuitBreaker.

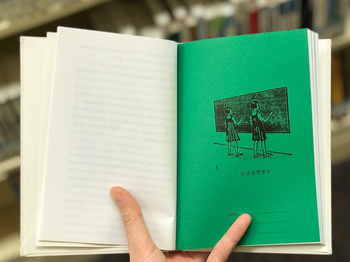

On Love by Edward Lam, published by ChenMiJi (from QRL’s zine collection)

QRL: When we think of zines, we think: grassroots, DIY, and free. This attitude towards zine-making is definitely present in our approach to showcasing and curating our collection. When we first started, our collection consisted of zines from our personal collections and publications that were sent to us from artists we reached out to online. Since then, we’ve added to our collection through picking up zines at different fairs, purchasing from artists we admire directly, or accepting gifts from friends who thought of QRL in their travels. The pop-up style of our library has also allowed us to present our titles in forms ranging from a table display to a makeshift bookshelf using milk crates.

![]()

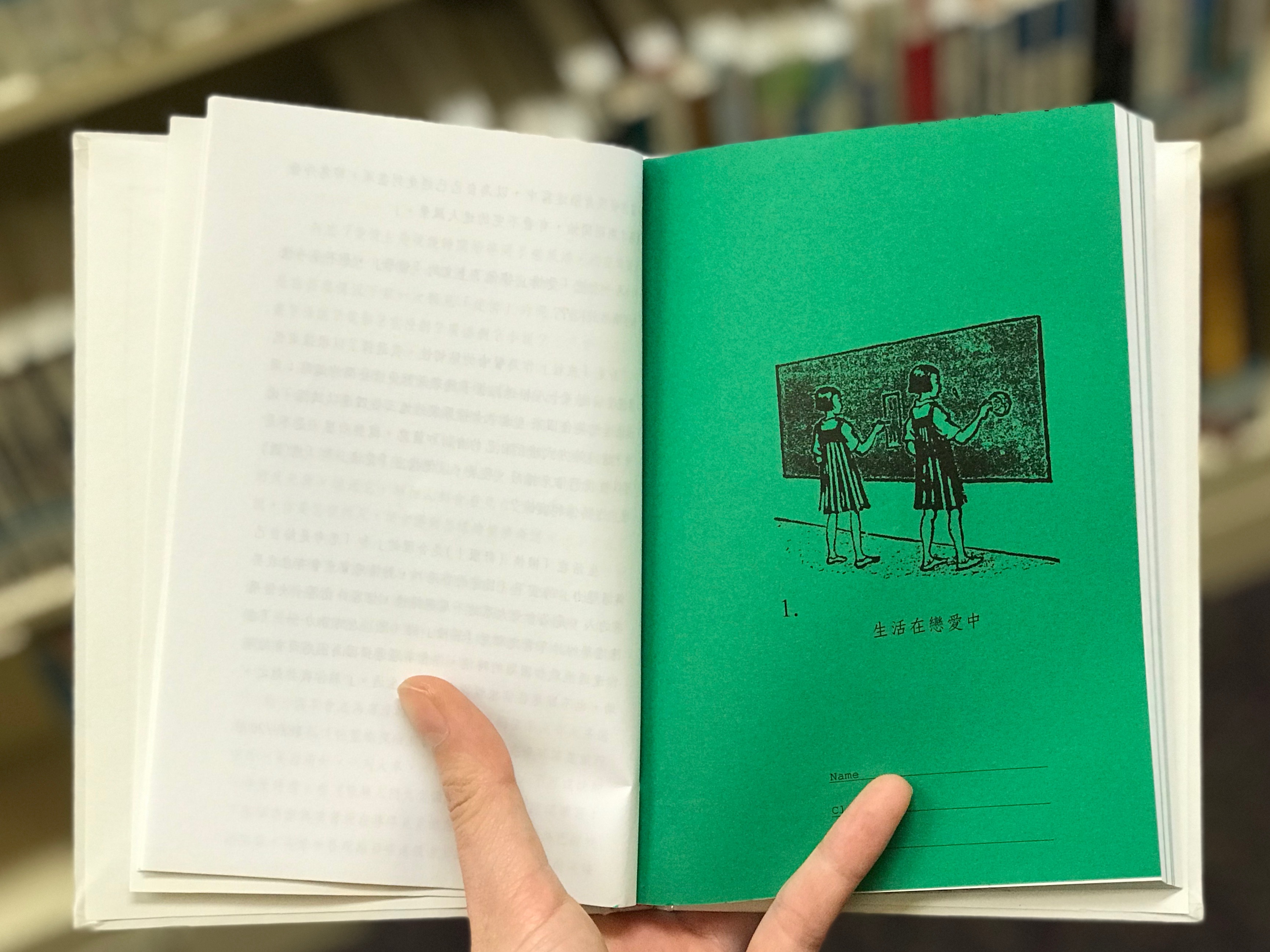

daikon Issue 3: Queer/Trans (from QRL’s zine collection)

Not having a physical location for QRL is both limiting and freeing. While we have the freedom to show-up in whatever space will have us, we also recognize that not having a space is due to the limitation of resources for many grassroots collections like ours. At the end of the day though, we always say that it’s not about the books themselves but the connections we make. What gives QRL it’s power is the relationships we build with our readers, fellow artists, and other queer folks worldwide.

QUEERSTMAS at soft/WALL/studs, 2018

We didn’t want a permanent venue because we like the idea of highlighting a new LGBTQIA+ friendly space every time we bring people together. Queer spaces in Singapore are few and far between – we’re mostly relegated to the nightlife. It’s been really exciting to encounter all these places that exist right under our noses that are actually really welcoming and loving. We worked with Camp Kilo in 2018, and The Moon, BUNKERBUNKER!! and soft/WALL/studs in 2019. All of these are spaces that are accessible to under-eighteens and people who may not want to be in a space where there’s dancing and loud music and drinking.

Queer ZineFest SG at Camp Kilo Charcoal Club, 2018

That approach has been kind of altered by COVID-19, because physical spaces are no longer an option for a lot of people. These few months have shifted our focus to the ways online planes can become brave spaces too. It’s not a new phenomenon – the Internet has always been an alcove for young Queer people! But I guess we’re learning how as organisations, we can be involved in building that safety net without intruding on the webs people have already built for themselves. For us, that looked like creating a Discord channel for LGBTQIA+ people in Singapore, and running Pajama Parties on Instagram Live during the CircuitBreaker.

OLS: Zine-making culture is incredibly multifaceted, and there’s a real spectrum when we begin thinking about what a zine can be or look like. As a result of this incredible diversity, some institutional archives and libraries have found it difficult to catalogue, collect or showcase zines.

Tell us about your team’s experiences with regard to collecting or showcasing zines: what has been rewarding, but what have you found limiting? How can we begin to expand our curatorial frameworks or archival vocabularies to embrace this range?

On Love by Edward Lam, published by ChenMiJi (from QRL’s zine collection)

QRL: When we think of zines, we think: grassroots, DIY, and free. This attitude towards zine-making is definitely present in our approach to showcasing and curating our collection. When we first started, our collection consisted of zines from our personal collections and publications that were sent to us from artists we reached out to online. Since then, we’ve added to our collection through picking up zines at different fairs, purchasing from artists we admire directly, or accepting gifts from friends who thought of QRL in their travels. The pop-up style of our library has also allowed us to present our titles in forms ranging from a table display to a makeshift bookshelf using milk crates.

daikon Issue 3: Queer/Trans (from QRL’s zine collection)

Not having a physical location for QRL is both limiting and freeing. While we have the freedom to show-up in whatever space will have us, we also recognize that not having a space is due to the limitation of resources for many grassroots collections like ours. At the end of the day though, we always say that it’s not about the books themselves but the connections we make. What gives QRL it’s power is the relationships we build with our readers, fellow artists, and other queer folks worldwide.

QZF: When we were planning for the 2020 fest (which couldn’t happen because of COVID), we definitely were thinking about how to present the full spectrum of Queer zinesters here while also being mindful of younger or more cautious attendees. Like, how do you present BDSM zines but still be respectful of those who don’t want to see this kind of content? Do you need to curate your festival accordingly, or do you leave it up to visitor discretion? This is a point of tension we’re still calibrating, and it's exciting to be working these kinks out together.

We’ve toyed around with unarchiving queer chapbooks in Singapore’s history, but research is a little bit out of our grasp right now as we’re focusing our energies on the present community. We’re curious to see if the eventual mode of documenting ephemera will be centered on digitisation or preservation. At this point, we’re just collectors with our own little zine economy of print matter and ideas.

QRL: We are most grateful for how these conversations and alliances help build solidarity around our shared joys and struggles, helping us imagine ourselves beyond borders and nationalities. Whether it’s about production notes on how to bind zines to exchanging new bodies of work about queerness, our conversations with other artists and collectives are the basis from which QRL draws its strength, pleasure and meaning. There’s an infinite power to seeing each other for how we want to be seen, and the publications and conversations around the library can facilitate a special kind of bond. As the pandemic has now created circumstances where being indoors is vital, we are hopeful that digital face-time and direct messaging can continue nourishing the bonds we’ve built face-to-face, and others we haven’t yet but are excited to forge. It helps us rest easier at night knowing that there are others in their bedrooms somewhere, making, building, and dreaming alongside us.

QZF: It's all thrilling so it's really hard to pinpoint a single thing about this that we're most jazzed for. But maybe the most immediately exciting thing is the possibility of a better-connected Queer Asia beyond the larger LGBTQIA+ institutions and organisations that currently have the mobility to cross geographical borders and start conversations. It's really exciting to think about what this might mean for younger or less mobile Queer people - to be able to connect to a much wider Queer community and access resources and support that might not be so readily available locally.

worms' (QZF) zine collection

![]()

Joy’s (QZF) zine collection

Queer Zinefest SG (QZF) is Singapore's first LGBTQIA+ zine festival. It was first held on July 14th, 2018, as a celebration of zine-making, queer art, and queer people. QZF also runs satellite events, zine workshops and hosts a Queer SG Discord channel.

Queer Reads Library (QRL) is a mobile collection of books and independently published zines centred around queer narratives and themes. Catalyzed by the removal of ten LGBTQ-themed children’s books from public shelves by the Hong Kong Public Library in June 2018, QRL was created in Fall 2018 to cultivate a space where queer people can gather and celebrate their narratives. In the beginning, we asked ourselves: “Where is the queer community in Hong Kong?”

QRL, much like queer gender and sexuality, is fuelled by the fluid, experimental, and (sometimes) mischievous. We are interested in where our library will take us and who wants to engage with queer histories and narratives, specifically through printed matter.

QRL aims to connect and collaborate with queer Asian people in the continent and in the diaspora. By virtue of our connections, our team spans across two continents. Currently, artist-publisher Beatrix Pang and artist-curator Kaitlin Chan are based in Hong Kong, while artist-writer Rachel Lau is based in Vancouver.

We’ve toyed around with unarchiving queer chapbooks in Singapore’s history, but research is a little bit out of our grasp right now as we’re focusing our energies on the present community. We’re curious to see if the eventual mode of documenting ephemera will be centered on digitisation or preservation. At this point, we’re just collectors with our own little zine economy of print matter and ideas.

OLS: This interview, in some ways, speaks to the very heart of both Queer Reads Library and Queer Zine Fest in that it is collaborative in nature and reaches across geographical boundaries. Tell us about what excites your teams most when it comes to the possibilities that these relationships open up, particularly around decentralising, organising and reimagining friendships, alliances and coalitions.

QRL: We are most grateful for how these conversations and alliances help build solidarity around our shared joys and struggles, helping us imagine ourselves beyond borders and nationalities. Whether it’s about production notes on how to bind zines to exchanging new bodies of work about queerness, our conversations with other artists and collectives are the basis from which QRL draws its strength, pleasure and meaning. There’s an infinite power to seeing each other for how we want to be seen, and the publications and conversations around the library can facilitate a special kind of bond. As the pandemic has now created circumstances where being indoors is vital, we are hopeful that digital face-time and direct messaging can continue nourishing the bonds we’ve built face-to-face, and others we haven’t yet but are excited to forge. It helps us rest easier at night knowing that there are others in their bedrooms somewhere, making, building, and dreaming alongside us.

QZF: It's all thrilling so it's really hard to pinpoint a single thing about this that we're most jazzed for. But maybe the most immediately exciting thing is the possibility of a better-connected Queer Asia beyond the larger LGBTQIA+ institutions and organisations that currently have the mobility to cross geographical borders and start conversations. It's really exciting to think about what this might mean for younger or less mobile Queer people - to be able to connect to a much wider Queer community and access resources and support that might not be so readily available locally.

worms' (QZF) zine collection

Joy’s (QZF) zine collection

Queer Zinefest SG (QZF) is Singapore's first LGBTQIA+ zine festival. It was first held on July 14th, 2018, as a celebration of zine-making, queer art, and queer people. QZF also runs satellite events, zine workshops and hosts a Queer SG Discord channel.

Queer Reads Library (QRL) is a mobile collection of books and independently published zines centred around queer narratives and themes. Catalyzed by the removal of ten LGBTQ-themed children’s books from public shelves by the Hong Kong Public Library in June 2018, QRL was created in Fall 2018 to cultivate a space where queer people can gather and celebrate their narratives. In the beginning, we asked ourselves: “Where is the queer community in Hong Kong?”

QRL, much like queer gender and sexuality, is fuelled by the fluid, experimental, and (sometimes) mischievous. We are interested in where our library will take us and who wants to engage with queer histories and narratives, specifically through printed matter.

QRL aims to connect and collaborate with queer Asian people in the continent and in the diaspora. By virtue of our connections, our team spans across two continents. Currently, artist-publisher Beatrix Pang and artist-curator Kaitlin Chan are based in Hong Kong, while artist-writer Rachel Lau is based in Vancouver.

Display Distribute

OBJECT LESSONS SPACE (OLS): Hi Display Distribute! Let’s start with the first question stemming from your selection of Kate Rich's Feral Trade project. This project is an exploration of the "carrying power" that people possess as travellers and moving bodies and the bodily involvement in transporting objects. For her, the organic quality of what is transported is part of the appeal, and she had claimed that "it would be much harder to ask people to carry something inert, like rocks or books".

How do you see the relationship between books, specifically art publications, and its movement across space both in its production and distribution process? Do you see an aesthetic quality about this network of distribution that you have set up via LIGHT LOGISTICS, or is this a matter of resistance, organization, and possible ethics?

DISPLAY DISTRIBUTE (DD): The Feral Trade project is a crucial point of reference for LIGHT LOGISTICS—so funny that you've happened upon this particular reference from Kate! Would be nice in light of that if there was an opportunity to see how she would reflect on our project. But in this context of being transported as illicitly carried goods (the question you have probably heard before at check-in: ‘Has anyone asked you to carry any extra items on board with you today?’), I’m not sure if I agree with the fact that the question of organicity contributes to appeal. The paranoia of a glass bottle of olive oil possibly breaking in my suitcase sounds quite unappealing, actually. But whether the carried items are books or cheese, the fact of being packed into checked luggage or shoved into a backpack actually points not to the qualities of the object itself, but to all the movements which flow with and around the cargo, and this is where the question of organic is much more interesting. Are capitalism, outsourcing, baggage handling, industrial food growth, our own bodies travelling thousands of kilometres for work or pleasure organic? The way we relate to objects is inherently mediated, but as the coronavirus pandemic has put into such stark clarity, things and certain ways of doing we previously took to be natural can suddenly come grinding to a halt, and human activity on earth can engineer ‘novel’ forms of organic transmission.

Display Distribute 『CATALOGUE』No. 4, initially intended for production in Guangzhou but by a stroke of luck reverted last minute to Hong Kong, courtesy of Display Distribute

Of course not everyone who is helping to courier a zine or bag of coffee beans will reflect to these scales, but for LIGHT LOGISTICS at least, there is a psychogeography at work which intends to make use of a ‘voluntary surveillance’ as a practice of observation—for a courier, who may for a delivery have to go to a part of the city he/she has never been before—and a question of revaluation: what metadata, or what stories, constitute a logistical record? Why should those working at the small-scale get ousted from participating in transnational, critical dialogues with other (semi-)autonomous practitioners?

Beyond the basic understanding of logistics as ‘moving people and stuff’, documentation and evaluation are the mechanisms which move together to make logistical operations work. This, to answer your other question, is both an aesthetic and an ethical question, and as a framework, platform and loose infrastructure, you could say perhaps that its aesthetics and ethics are premised upon modes of social, political and artistic organisation.

OLS: The way you look at organicity is really fascinating. Perhaps what you mentioned about putting oneself up to "voluntary surveillance" is a way of resistance by reclaiming agency from surveillance as an inevitability in today's age. Your project Shanzhai Lyric can be read as a reassertion of autonomy as well: understanding it through a post-colonial lens, it is a way of rewriting authenticity and cultural imperialism through challenging language. Display Distribute runs from Hong Kong, in which the operant languages include English, Mandarin Chinese, and Cantonese ‑ your website uses both English and Chinese as well, and as a bilingual reader the differences which emerge from translation are really interesting to me.

What is the importance of language and translation in your work?

DD: Resistance is certainly a considered factor, although I don't think it is possible to heroicise our couriers so much in the vein of how they call food delivery workers ‘frontline personnel’ these days. Travel is after all a privilege, and we have been piggybacking upon it, so to speak. But the attentiveness to movement is something that can be read in so many ways—as reconnaissance, instituent practice, or Situationist game, even mindfulness, and that diversity is something that becomes manifest in the project over time, in seeing the various ways that routes are documented, because every courier will attend to it differently. Even myself, having been a frequent mule—what I see and choose to record depends greatly upon the energy required to take notice via images or sound or words. Everything is framed within the banal structures of logistical time and place positioning, but so many things are left out and so many unimportant other details put in. This instability of the data is perhaps part of that resistance you mentioned.

Interns of Hong Kong art space Para Site busy with post-production deconstructions of 『CATALOGUE』No. 4 at the opening of Bicycle Thieves, June 2019; Photo Credit: Lily Yi Yi Chan for Para Site

I cannot speak so much for Shanzhai Lyric as I am not involved with that project; Display Distribute operates as a sort of multi-headed hydra whereby we are not all working on the same things, but as we tried to linguistically experiment with here in a little redux of another to be crucially acknowledged initiative, the Minor Compositions imprint of Autonomedia, there is a kind of ‘gobbledygook’ which we are weaving and wading through and manifests the somewhat perplexing and/or evasive totality. And that is simply to say that there is no such totality, and no centrality as what you point out with the language plays at work. The Chinese and English are not always one-to-one but hopefully they can take on certain forms of nuance for each of their bodies of readers. These shades of Canto-Manda-English that appear are a crucial part of the Pearl River Delta vernacular that has given rise to phenomena like parallel traders and Display Distribute, and with text and textuality being a crucial part of many of our practices, language does become one of the central playing fields. The border between Hong Kong and the mainland is also the first threshold of translation that inspired the initial projects of Display Distribute, and as we’ve seen ongoing since the handover—most recently with the 4/17 Statement by the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the HKSAR and increasingly threatening interpretations of Hong Kong’s very fragile Basic Law—language, the subtle things that get left out and the various ways of manoeuvring through syntax cannot not be considered.

OLS: The process of playing with or navigating language—disseminating texts, copying, pasting, and then perhaps reposting—can then bring about really interesting divergences, and it brings to mind chain letters – which was something you picked out for this conversation as well. Chain letters were a hallmark of the 2000s and early 10s, they continue to exist today in the form of copypastas, but the possible distinguishing factor is that of the encouragement to share, either through motivation of a reward or a threat.

With the various strands of Display Distribute in terms of ideas, performances, exhibitions and partnerships, would you say that the projects have been working towards a more emotive or collaborative mode of transmission that rallies against mainstream or neoliberal modes of consumption? What do these possibilities look like?

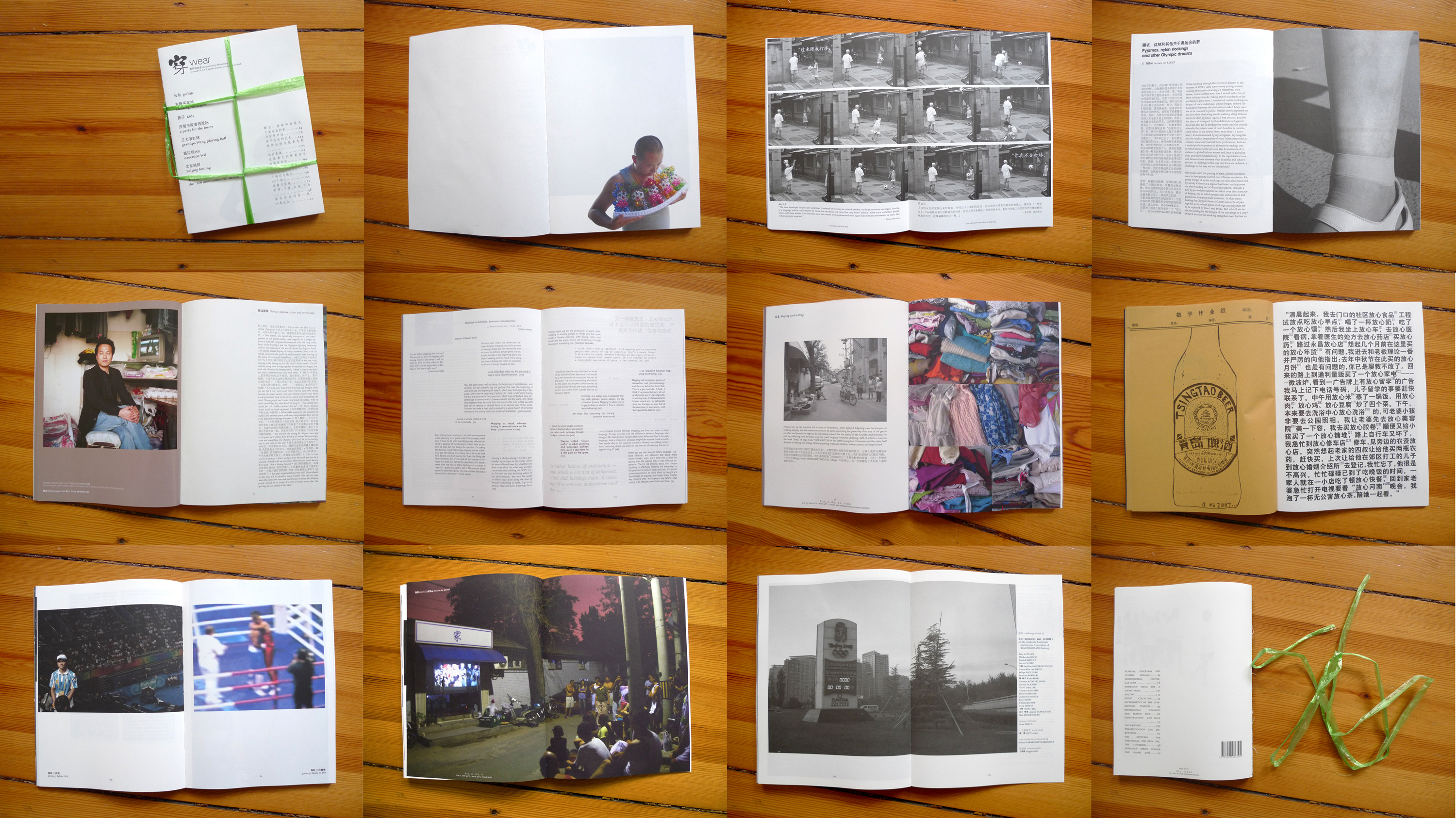

wear journal number one, courtesy of HomeShop

DD: Oh, I’m really happy you brought this up again! I have been thinking about chain letters recently simply because they seem to have made a pandemic era resurgence, sped up for 2020 internet in that it seems—from the perspective of my inbox at least—to have only been a few weeks-long revival. I come from the last mega-transition generation of the world before the Internet (when it was still spelled with capital ‘I’). So those years when chain letters were circulating widely were a time of both naïveté and seriousness in that we took the threats and rewards seriously because it was all so simply new and the repercussions were not calculable. I’ve brought it up again as a point of reflection for Display Distribute because it is an immensely poignant example of the use of affective relations in a networked economy that links money, OL/IRL connections and partial anonymity by way of the simple orchestrated parlance of text. Scenarios are set up for someone to enter into a pyramid scheme, interest group or superstitious belief system, and the end results can never be fully confirmed, but we participate anyway. LIGHT LOGISTICS works in a similar way, juxtaposing voluntarism, contingency and chance with the real tracing of networks and affect. There may be a concrete result in that a book reaches point B from point A, but that is not even the most prized value of the project for us. While we are still running a logistical operation so ‘aim to deliver’, I will still vouch instead for storytelling, cracks in infrastructure, and inefficiency.

OLS: On that note of meandering and subverting, it brings to mind something else you picked out for our chat — the prevalence of book pirating and the presence of pirate archives all over China and Southeast Asia. What do you make of the term “piracy” when it comes to its relationship to ideas such as legitimacy and autonomy? Often, there is a certain image—that of being polished or almost immaculate—when we think of how official archives or museums present our histories. How can making things ourselves (piecing images, texts, and sources together ourselves) serve as an effective counterpoint to the role of said institutions, especially in the context of the internet and the democratisation of access?

DD: Piracy seems to have always been associated with a kind of irreverence for societal norms, notions of propriety and property, which can in many ways be upsetting to any one of us who may have a claim upon something of potential value, whether we are the ones who ‘created it’ or not. If we look into the lineage behind this impulse, there is a history that traces back to the question of the commons and movements of enclosure from 15th century England. But looking from our perspective here in the East, it does beg the question of whether our own forms of ‘legitimacy’ and so-called ‘autonomy’ can only be ultimately defined from these pre-capitalist roots in ye olde England? A number of scholars have attempted to retrace alter-genealogies to this question, and one very articulate and grounded reference I can recommend is Lawrence Liang, Prashant Iyengar and Jiti Nichani’s How Does an Asian Commons Mean. Another is Byung Chul Han’s Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese, one of the volumes in our SECOND(hand)MOUNTAIN(fortress) series, a funny edition that has been scanned by mobile phone and Google translated from the original German. The official English translation came out later than our edition, which we do intend to incorporate into further printings, but for the time being, if an English reader needs, we’ll send the new PDF as well.

One crucial thing that Liang, Iyengar and Nichani remind us is how the first pirates emerged in fact because they were dispossessed from the commons, and as these ‘outcasts of the land’, it was the pirates who ‘would mutineer against the conditions of their work, and create an alternative order challenging the division of labour and of capital’. So this links forward to the latter half of your question, where we re-examine what may have been viewed as piracy and looting and reconsider what can actually be self-initiated, alter-practices of survival and knowledge-testing. DIY publishing practices will always, by virtue of being the testing of ideas in the public sphere, represent microscopic visions of what alternative orders can be created to challenge hegemonic structures. There is a great line from an essay I recently read which says, ‘The little magazine had been and remains, at least for a time, the single most efficient path to the deictic claim that says “we're here, too.”’

OLS: Now that we’re speaking directly to the possibilities a do-it-yourself attitude can afford us, particularly in the realm of publishing, could you please expand a little on what book making means to you? How has your understanding of or relationship to book making or the book form evolved over time?

DD: Looking back now, I think it’s possible to say that the trajectory of my relationship to publishing has run what could be considered a counter-productive course relative to the modernist call for expansion and commercialisation (Bigger! Better! Faster!). Part of my educational background is actually in fashion design, an obviously commercial industry dominated by surface aesthetics and big money, and that collided with the beginning of my work as a so-called artist practicing in China, not academically trained yet with access to the optimistic possibilities of material production available at the time (meaning the years immediately before and after the 2008 Beijing Olympics). This was the period in which we began our own DIY publishing practice in the form of an independently produced journal for the artist-run space I was active with at the time, called HomeShop. It was not a zine, neither handmade nor photocopied, but beautifully offset print with multiple carefully chosen papers, somehow aesthetically still in resistance to commercial appeal but by virtue of being a factory-made production, perhaps it could be considered a way in which a small-scale, marginalised project seeks to stake a claim upon its validity within the archive of contemporary art. We were also saying, ‘We’re here, too’.

But while independent publishing and zine culture has grown in mass appeal over time, China’s rising economy combined with narrowing freedoms means that the space for content ‘at the margins’ or ‘between the lines’ is being squeezed out. In recent years, I have been refused as a client both by low-cost digital printing shops as well as offset factories, the former because my order (different colours of covers for different titles) veers from the producer’s cost-efficiency standard (too 麻煩 mafan!), and the latter because printing sensitive content would risk the factory being forcibly shut down by authorities.

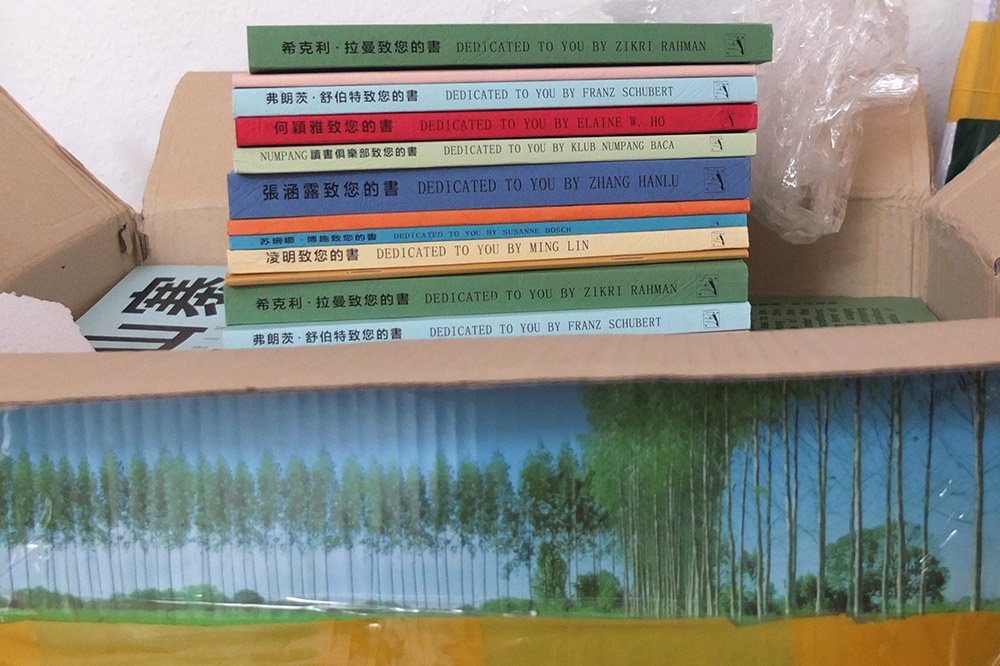

So in a way, our status as pirate, smuggler and hacker is exactly as was written above, where we have been ousted from the market and accessibility to resources diminished. To continue doing what we would like to do, it seemed to make sense that we should in that very old school, Marxist sense, ‘take back the means of production’ ourselves. So that means trying to make more books ourselves, to try to reconsider the balances between the material craft of book production and its content without being nostalgic or trying to glorify the handmade. To go back to the initial reflection of counter-productivity, this means that over time, our print-runs are getting smaller and the whole process from start to finish is slower. But as with LIGHT LOGISTICS, obviously we don’t have a problem with that.

Digital print-on-demand copies of the Display Distribute ‘SECOND(hand)MOUNTAIN(fortress)’ imprint

OLS: We’ve touched on quite a few ideas throughout this interview including small batch productions, inefficiency as an alternative framework, and the allure of DIY culture. There are so many strands of inquiry to your work with Display Distribute, and these research questions or interests are constantly evolving. To wrap up our conversation, could you please speak to whether there has been a philosophy, a praxis or even an attitude that binds all of these interests together?

DD: How about answering your question with a praxis of the question itself? The diversity of inquiry can on one hand simply be the distractedness of many interests, many references and/or inspirations, maybe otherwise simply giving space to the multi-headed hydra of collaboration. But a most general formula is simply beginning from the question itself—questioning everything, second-guessing all. It’s a possibly painfully ambivalent route, but it’s also the starting point for trying things a little bit differently, imagining and practicing another possible way.

Display Distribute is a thematic inquiry, distribution service, now and again exhibition space and sometimes shop founded in Kowloon, 2015. Seeping via the capricious circulation patterns of low-end globalisation into other subaltern networks and grammars, recent activities include the experimental infrastructure LIGHT LOGISTICS, poetic research and archival unit Shanzhai Lyric and a peripatetic radio programme of hidden feminist narratives known as Widow Radio Ching.

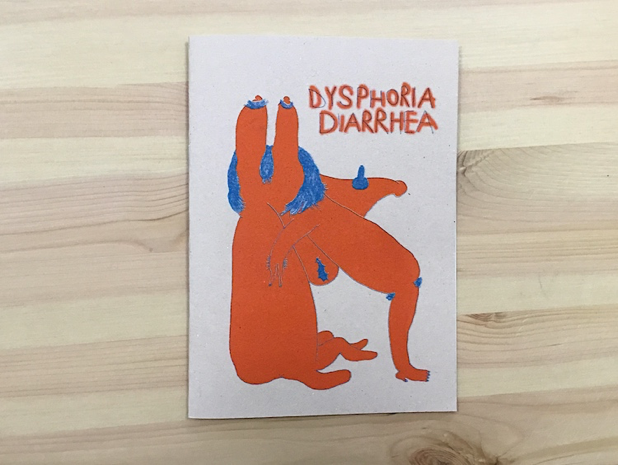

Photo Credit: THEBOOKSHOW

SONG NIAN (SN): Pictures of My Life was immediately interesting to me because it doesn't really fall into the typical categories. It doesn't fit with how people typically think about photobooks or coffee table books. Pictures feels like an encapsulation of several different materials which the artist has put together as a book. It mainly contains paintings and photographs – some of the photographs are taken by the artist himself, others are earlier photos of Ueda's childhood taken by his father. The artist also incorporates into his book these texts in Japanese, along with their English translation.

![]() Pictures of

My Life,

Junpei Ueda. Image Credit: Junpei Ueda

Pictures of

My Life,

Junpei Ueda. Image Credit: Junpei Ueda

SN: Beginning with the cover of the book, you are immediately confronted not with a photograph but a painting – a portrait of the artist's younger self. What is revealed to you through the book is the artist's memories of his childhood, followed by the passing of his mother and then the passing of his father. After his mother had committed suicide, his father, not being able to deal with his grief, followed suit. What you can see is the artist trying to make sense of the situation. Towards the end of the book, there is a photograph of Ueda, his wife, and their two daughters. I had spoken to the artist particularly about this, and he said that this was his way of putting forth a reassurance both into the world and to his parents who had passed.

SN: Pictures of my Life feels less like a book and more like an artefact that is put together with different materials which reveal different parts of his life. While going through the book from front to back, it doesn't feel static or linear; there are pauses in the book that allows the reader to take a step back or retreat with the artist into where his mind is, and to listen to what he wants to tell us via the text. That is why I think that the book has such a strong emotional power, which is why I wanted to share this work.

LEANNA TEOH (LT): I think the most important thing about the book, both as an art medium and as an art object, is its portability and longevity. Having a book is like having an exhibition that lives beyond the space; you can view it at any time and any place, with a unique intimacy. Unlike an exhibition, you won't be interrupted by other people viewing the work at the same time. The book is a very intimate object.

I don't really know what, for me, is the difference between the book as a medium and as an object. What we are trying to advocate is that the book is a mode of expression, and that it is different from, for example painting and photography, because you can propose a narrative within the medium.

OBJECT LESSONS SPACE (C): Hi Song Nian and Leanna, thanks for having us with you in your studio today. Let’s begin with talking about your first selection, Picture of My Life. This is a self-published book, which is handmade by artist Junpei Ueda through a workshop titled Photobook as Object. It contains photographs, illustrations, and folded pieces of written correspondence with his parents. Do you see a particular physicality that comes with books and bookmaking?

SONG NIAN (SN): Pictures of My Life was immediately interesting to me because it doesn't really fall into the typical categories. It doesn't fit with how people typically think about photobooks or coffee table books. Pictures feels like an encapsulation of several different materials which the artist has put together as a book. It mainly contains paintings and photographs – some of the photographs are taken by the artist himself, others are earlier photos of Ueda's childhood taken by his father. The artist also incorporates into his book these texts in Japanese, along with their English translation.

SN: Beginning with the cover of the book, you are immediately confronted not with a photograph but a painting – a portrait of the artist's younger self. What is revealed to you through the book is the artist's memories of his childhood, followed by the passing of his mother and then the passing of his father. After his mother had committed suicide, his father, not being able to deal with his grief, followed suit. What you can see is the artist trying to make sense of the situation. Towards the end of the book, there is a photograph of Ueda, his wife, and their two daughters. I had spoken to the artist particularly about this, and he said that this was his way of putting forth a reassurance both into the world and to his parents who had passed.

SN: Pictures of my Life feels less like a book and more like an artefact that is put together with different materials which reveal different parts of his life. While going through the book from front to back, it doesn't feel static or linear; there are pauses in the book that allows the reader to take a step back or retreat with the artist into where his mind is, and to listen to what he wants to tell us via the text. That is why I think that the book has such a strong emotional power, which is why I wanted to share this work.

OLS: What do you see as unique to the book both as a medium for art, and as an art object?

LEANNA TEOH (LT): I think the most important thing about the book, both as an art medium and as an art object, is its portability and longevity. Having a book is like having an exhibition that lives beyond the space; you can view it at any time and any place, with a unique intimacy. Unlike an exhibition, you won't be interrupted by other people viewing the work at the same time. The book is a very intimate object.

I don't really know what, for me, is the difference between the book as a medium and as an object. What we are trying to advocate is that the book is a mode of expression, and that it is different from, for example painting and photography, because you can propose a narrative within the medium.

SN: When we look out for photographic works, we look out

for works that somehow—I don't want to say they only make sense as a book, but

in particular when it is being produced as a book or publication—demonstrate

that the concept or message of the work is able to extend beyond merely working

as images; be that in a frame, a slideshow or a projection.

Back to the physicality of the book, the way a book is crafted matters. All these elements—from the design, the cover, the layout, and even the end pages, the binding and inserts—lend layers to the way we experience an artwork in the book medium.

SN: Gaining acceptance for photography in the art world has always been an uphill task. Fortunately, in the last ten to fifteen years, we have seen an improvement in the way photography is being perceived in the art world. When photography first started to be mass produced, it was used for a very specific purpose in editorial work, journalism and newspapers – in terms of disseminating messages. That is what people saw to be the main role of photography. I think we see photography coming up slowly with this medium being explored within various art disciplines.

The relationship between photography and print is related to that of performance art and video, which also have always been very close and very strongly bound together. Performance work needs to firstly exist by itself, but for it to continue to exist, or for people to know that it has once existed, it then depends on the video work that was done during the live performance.

There is another whole conversation that can be had about the movement from painting to photography. There has always been a painting-versus-photography dialogue going on, of, for example, which one is better. Within the art world, photography gained traction at a slower pace, possibly because it was produced in editions. As the number of editions become smaller, we start to see it becoming more accepted by collectors. People also become more willing to buy photography work as fine art. Print will always be important to photography, even as we start to see photography work in other presentation formats. I'm quite hopeful about the acceptance of photography in the art world. It's changing, just slowly.

SN: I think we are coming up with ways to firstly enable people to produce content, in terms of the programmes, exhibitions, open calls and workshops. We are also finding ways to bridge the distance between those making the books, and everyday people, who also otherwise access photography on a daily basis.

This project is still very young - we started in 2014. Prior to THEBOOKSHOW working more actively, we did observe some efforts by other groups or initiatives pertaining to the photobook but there is no prolonged effort in looking at the photobook medium. In terms of providing opportunities for people who create, we have also started several initiatives such as open calls, which lead to exhibitions, which lead to prizes and awards. In terms of showcasing books, we also actively promote at international art book fairs and work on partnerships with collaborators from overseas to disseminate or to exhibit. A healthy exchange would be one where we show books from overseas, then have our books shown there too.

There are a lot of things we're doing at the same time, all with the hope of growing the appreciation of the photobook as a medium of art.

![]()

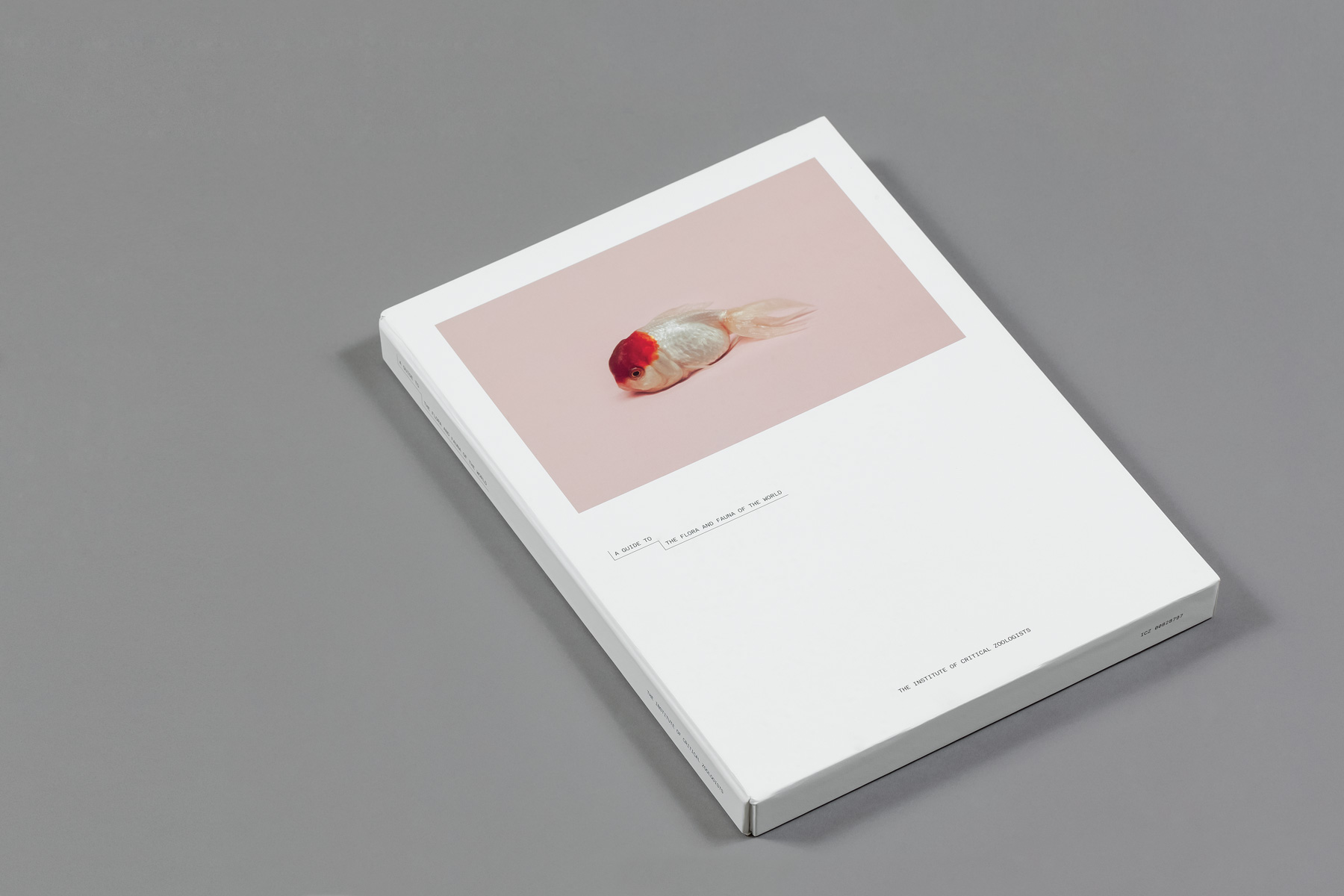

A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Institute of Critical Zoologists

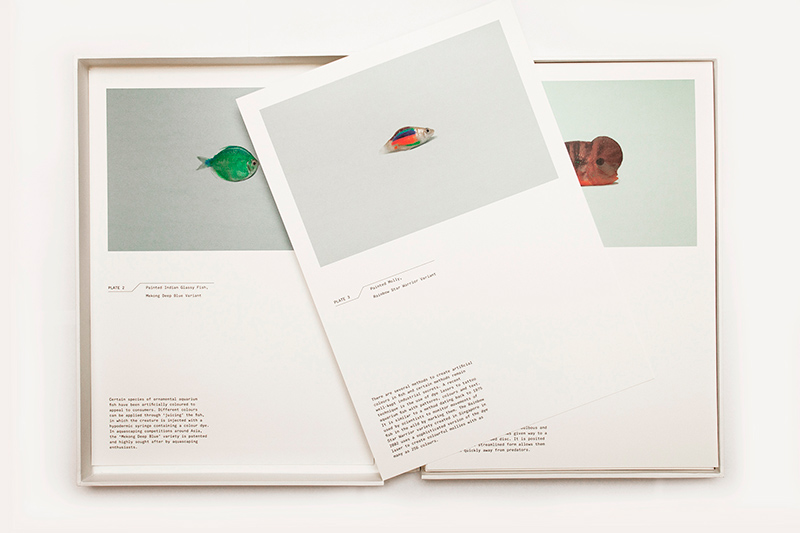

SN: A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World was initially self-published. Subsequently, Robert Zhao submitted it to the Steidl Book Award: Asia Open Call, which was when it was selected to be one of the eight books to be published by Gerhard Steidl. The edition that Steidl published is slightly different from his original self-published version. If you look towards the back of the book, there are many of these smaller booklets that are included in the box, which were not in the first edition. I selected this book because it has particularly received quite a lot of attention internationally; I think the main reason for that is because many people are already aware of Robert's work and his practice. I feel that this is the pride and joy of Singapore's self-publishing efforts.

Back to the physicality of the book, the way a book is crafted matters. All these elements—from the design, the cover, the layout, and even the end pages, the binding and inserts—lend layers to the way we experience an artwork in the book medium.

OLS: What do you see as the importance of print to photography? Do you see photography as adjacent to or contained within art?

SN: Gaining acceptance for photography in the art world has always been an uphill task. Fortunately, in the last ten to fifteen years, we have seen an improvement in the way photography is being perceived in the art world. When photography first started to be mass produced, it was used for a very specific purpose in editorial work, journalism and newspapers – in terms of disseminating messages. That is what people saw to be the main role of photography. I think we see photography coming up slowly with this medium being explored within various art disciplines.

The relationship between photography and print is related to that of performance art and video, which also have always been very close and very strongly bound together. Performance work needs to firstly exist by itself, but for it to continue to exist, or for people to know that it has once existed, it then depends on the video work that was done during the live performance.

There is another whole conversation that can be had about the movement from painting to photography. There has always been a painting-versus-photography dialogue going on, of, for example, which one is better. Within the art world, photography gained traction at a slower pace, possibly because it was produced in editions. As the number of editions become smaller, we start to see it becoming more accepted by collectors. People also become more willing to buy photography work as fine art. Print will always be important to photography, even as we start to see photography work in other presentation formats. I'm quite hopeful about the acceptance of photography in the art world. It's changing, just slowly.

OLS: How do you see THEBOOKSHOW’s role then, as a mediator or bridge of sorts?

SN: I think we are coming up with ways to firstly enable people to produce content, in terms of the programmes, exhibitions, open calls and workshops. We are also finding ways to bridge the distance between those making the books, and everyday people, who also otherwise access photography on a daily basis.

This project is still very young - we started in 2014. Prior to THEBOOKSHOW working more actively, we did observe some efforts by other groups or initiatives pertaining to the photobook but there is no prolonged effort in looking at the photobook medium. In terms of providing opportunities for people who create, we have also started several initiatives such as open calls, which lead to exhibitions, which lead to prizes and awards. In terms of showcasing books, we also actively promote at international art book fairs and work on partnerships with collaborators from overseas to disseminate or to exhibit. A healthy exchange would be one where we show books from overseas, then have our books shown there too.

There are a lot of things we're doing at the same time, all with the hope of growing the appreciation of the photobook as a medium of art.

OLS: One such award was the Steidl Book Award, in which THEBOOKSHOW had helped to put together the finalist showcase. One of the winners was Robert Zhao’s A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, which you have also chosen as part of your selection. Tell us more about that.

A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Institute of Critical Zoologists

SN: A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World was initially self-published. Subsequently, Robert Zhao submitted it to the Steidl Book Award: Asia Open Call, which was when it was selected to be one of the eight books to be published by Gerhard Steidl. The edition that Steidl published is slightly different from his original self-published version. If you look towards the back of the book, there are many of these smaller booklets that are included in the box, which were not in the first edition. I selected this book because it has particularly received quite a lot of attention internationally; I think the main reason for that is because many people are already aware of Robert's work and his practice. I feel that this is the pride and joy of Singapore's self-publishing efforts.

What we see with A Guide is not a typical

book with bindings; it makes a lot of sense for the book to be presented in a

plate format. This is also in line with his practice, as he had also come up

with the Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ). We see plates used in

scientific journals. That's the kind of terminology and format that they use in

the scientific process. Robert uses that kind of reference heavily such that

his books have the aesthetics of research reports. I think that's why people

find this book to be a breath of fresh air, compared to the usual art books and

photobooks one usually encounters.

LT: I think the biggest hurdle is cost, especially in Singapore where printing is a lot more expensive than in other places. For example, the cost of maintaining the printing machines themselves is already high, because we must get technicians to come in from overseas, which drives up the base price. Other than the cost of printing, it really depends on your network to get the book out into the open. Most of the time self-publishing artists market their books either through competitions and open calls like ours, or they show their work in fairs. These are the venues through which readers find out about artbooks, other than at bookstores. To participate in a fair also generates additional cost. The cost of printing and marketing are the hardest things; it's everything to do with cost.

SN: That aside, we felt that the network and infrastructure for helping people with self-publishing was almost non-existent in Singapore. That's what we want to do - we see ourselves as a platform. We started out with that idea of wanting to provide more opportunities for people. As the years went by, we realised that apart from the cost, it's also about getting access to the right kind of designers and printers. Apart from budget, and access to the right kind of people and network, we found that storage and dissemination also play a key part. You can self-publish a hundred copies, three hundred copies, a thousand copies - but how are you going to move the books? I think this also proved to be quite a challenge when it comes to self-publishing.

Of course, there are things like kickstarter campaigns, but those are also slowly getting saturated and losing their novelty. There have been some successful cases, for example Dark Cities by Shyue Woon, which was also part of our project First Draft. He won a $5000 sponsorship by Allegro, a local printing company, through First Draft. In addition to that, he also launched a kickstarter campaign, which I felt was rather effective. Dark Cities is now onto a second edition, which is again aided by a kickstarter campaign.

If we look away from the perspectives of people creating the work, there are also challenges from a publisher’s point of view. That is something that THEBOOKSHOW is experimenting with. What we find to be a challenge is having access to a sufficient amount of works to select from and to publish. In alignment with the kind of publishing work that we are slowly planning to do, we have to also put in motion avenues, channels, or initiatives to encourage people to make more works. The fact is that if there's nobody making, there's no one for us to publish. Since we focus on Singaporean artists, we have a smaller pool to work with. It's then even more important for us to get the momentum going. Only if the selection pool gets bigger, then we are able to really sieve out the works that are of a higher quality.

One such work would be The Mountain Survey by Marvin Tang, which he published in a very small run in 2016 as part of a show of the same name. Marvin's practice relies heavily on research. For this project, he started with looking at the Xiao Guilin quarry landscape. He then realised that granite, as a resource, played a pivotal role in the narrative of nation-building. He found out that Xiao Guilin wasn't the only one, that there were other quarries and that Singapore sits on granite. That explains why it was also one of the more common resources that was being used in building.

What I was captivated by was the mix of research materials that he found, which he used to really inform different parts of the book. We see different types of images. Some were very formal representations of the landscapes in these decommissioned granite quarries. Others show people just staring at the landscape. I found that to very impressive – Marvin’s observation didn’t end with simply looking at whatever was in front of him. He saw what really makes up the landscape. He realised that people were spending such a considerable amount of time at these places, staring off into the distance at these fake mountains, with their backs to the world. There were all these different kinds of traces people left around the vicinity. It's not just a monotonous presentation of all the different granite quarries, but also showed the way people behave, respond and react to these landscapes, that are now being positioned as a place solely for recreational enjoyment, which is held in stark comparison to all the exempt historical purposes that these granite quarries used to serve.

OLS: This is originally a self-published book. In many of your open calls, you specifically ask for self-published or unpublished work. What is the importance of and difficulties in self-publishing?

LT: I think the biggest hurdle is cost, especially in Singapore where printing is a lot more expensive than in other places. For example, the cost of maintaining the printing machines themselves is already high, because we must get technicians to come in from overseas, which drives up the base price. Other than the cost of printing, it really depends on your network to get the book out into the open. Most of the time self-publishing artists market their books either through competitions and open calls like ours, or they show their work in fairs. These are the venues through which readers find out about artbooks, other than at bookstores. To participate in a fair also generates additional cost. The cost of printing and marketing are the hardest things; it's everything to do with cost.

SN: That aside, we felt that the network and infrastructure for helping people with self-publishing was almost non-existent in Singapore. That's what we want to do - we see ourselves as a platform. We started out with that idea of wanting to provide more opportunities for people. As the years went by, we realised that apart from the cost, it's also about getting access to the right kind of designers and printers. Apart from budget, and access to the right kind of people and network, we found that storage and dissemination also play a key part. You can self-publish a hundred copies, three hundred copies, a thousand copies - but how are you going to move the books? I think this also proved to be quite a challenge when it comes to self-publishing.

Of course, there are things like kickstarter campaigns, but those are also slowly getting saturated and losing their novelty. There have been some successful cases, for example Dark Cities by Shyue Woon, which was also part of our project First Draft. He won a $5000 sponsorship by Allegro, a local printing company, through First Draft. In addition to that, he also launched a kickstarter campaign, which I felt was rather effective. Dark Cities is now onto a second edition, which is again aided by a kickstarter campaign.

If we look away from the perspectives of people creating the work, there are also challenges from a publisher’s point of view. That is something that THEBOOKSHOW is experimenting with. What we find to be a challenge is having access to a sufficient amount of works to select from and to publish. In alignment with the kind of publishing work that we are slowly planning to do, we have to also put in motion avenues, channels, or initiatives to encourage people to make more works. The fact is that if there's nobody making, there's no one for us to publish. Since we focus on Singaporean artists, we have a smaller pool to work with. It's then even more important for us to get the momentum going. Only if the selection pool gets bigger, then we are able to really sieve out the works that are of a higher quality.

One such work would be The Mountain Survey by Marvin Tang, which he published in a very small run in 2016 as part of a show of the same name. Marvin's practice relies heavily on research. For this project, he started with looking at the Xiao Guilin quarry landscape. He then realised that granite, as a resource, played a pivotal role in the narrative of nation-building. He found out that Xiao Guilin wasn't the only one, that there were other quarries and that Singapore sits on granite. That explains why it was also one of the more common resources that was being used in building.

What I was captivated by was the mix of research materials that he found, which he used to really inform different parts of the book. We see different types of images. Some were very formal representations of the landscapes in these decommissioned granite quarries. Others show people just staring at the landscape. I found that to very impressive – Marvin’s observation didn’t end with simply looking at whatever was in front of him. He saw what really makes up the landscape. He realised that people were spending such a considerable amount of time at these places, staring off into the distance at these fake mountains, with their backs to the world. There were all these different kinds of traces people left around the vicinity. It's not just a monotonous presentation of all the different granite quarries, but also showed the way people behave, respond and react to these landscapes, that are now being positioned as a place solely for recreational enjoyment, which is held in stark comparison to all the exempt historical purposes that these granite quarries used to serve.

Mountain Survey, Marvin Tang. Photo Credit: Marvin Tang

OLS: The production process that goes into a work seems to be very important to you. Your workshop project Dirty Laundry especially focuses on this process of bookmaking, and the notion of what makes something "suitable" or "good", or "ready" to be published.

LT: Dirty Laundry was made to involve people who were not "in the know" of the art world. The workshop starts with the topic of how to assemble a book and the more technical aspects of bookmaking. During the process, we also try to subtly instil ideas of what a book can be, and talk about how to view and understand a book. All our programmes are geared towards educating the public about the book and how it can be a form of art.

SN: Dirty Laundry was set up as a workshop which involves contribution by and from the participants. In this edition, we capped it at twenty participants. Each are asked to bring between thirty to forty images, printed in whatever kind of format they prefer, as long as it's smaller than an A4 size. Everyone will come in with images that they deem to be "bad", and we start the discussion from there. In this day and age, with the way we use photography in social media, we can't run away from the fact that people always want to present the best side of things; they always try to show how much they're enjoying their lives and how good they have it. I feel that there are a lot of images that have fallen through the cracks. I also think the concept of a "bad" photograph is quite problematic. What we are after in Dirty Laundry is the intention of the image, of what it is really meant to convey or say. That's why we decided to invite people to bring in what they think are "bad" photographs.

At the start of the workshop everyone will lay their images on the table, and they will talk about their images and why they think it is a "bad” photograph. Through that sharing, participants will start to realise that everyone's interpretation of "bad" is varies. Looking at each other's photos, sometimes they will find that the photos is only "bad" from that person's own perspective.

After they take the time to look at and hear about the images, participants are then given time to put together a zine or a book with the images that belong to everybody. It's a free-for-all kind of approach, where you are allowed to use not just your own photos but also other people's photographs.

The name Dirty Laundry comes about because everyone brings in their bad photos to the table and share about it openly. Though we definitely hope for some profits from this project, we started it not specifically to earn money, but instead as a project of content-production or creation. It is a way for us to collect images of the vernacular, which comes from participants of different groups, ages and backgrounds. The images that they provide are all taken by themselves. We found that to be a good way of building up an archive of images of the everyday, not taken by artists or photographers, but coming in from different walks of life. Dirty Laundry has slowly evolved to be something that's very central to what THEBOOKSHOW does and what we believe in.

THEBOOKSHOW is an avenue for artists to showcase self-published art books in exhibitions and art festivals. It connects the arts community through showcases and activities centering the art book and its presentation, moving away from the conventional form and bringing upon renewed perspectives of the medium.

Robert Zhao

SGABF: Hi Robert, thanks for having us over at your studio. What are you working on today?

ROBERT ZHAO (RZ): I had a meeting with Gideon and Jamie from Temporary Press. They are working on the second edition of Singapore, Very Old Tree. It’s a project I did in 2015 in which I interviewed 30 people with personal stories of old trees. The content is very specific so I did not expect many people to like it, mainly because I thought trees made colder subjects than animals. I had the impression that birds and insects would seem more charismatic and trees were more difficult to relate to. Most of my books don’t sell, but this was one of those that sold. As it turns out, even after selling out, people were still asking about it. That is why I decided to republish it.

Singapore, Very Old Tree, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Tongue Journal

SGABF: How do you go about looking for a designer who resonates with your practice?

RZ: I try to look for books that I like locally and see how the designers work with the content. Of course the designer must also be interested in my practice. I leave the technicalities to them because I’m already working on printing and framing my own photographs. Most of my meetings with the designers at the beginning are about the concept; what the work is really about and what the book should be doing. After that I trust them to do whatever they want. You must have that chemistry; it’s important to find a designer that really understands your work so they can help translate it into a book.

As an artist, you’re always just talking to yourself. You’re thinking and doing everything yourself until you set up the exhibition, or you speak to someone who has no idea what you’ve been thinking for the last three months, then they ask a lot of What’s this? and What’s that? And you realise, Actually, I also don’t know. You’re forced to make connections that you perhaps haven’t thought about previously or that you’re trying to avoid. Once the book comes out, I guess you can be abstract in some parts but you have to be logical also. The narrative has to flow and the designers are usually quite observant about how the information flows. So that dialogue is very good for me.

SGABF: You have been making books for almost 10 years now, starting with The whiteness of a whale. How did you start?

RZ: The whiteness of a whale was created in 2010. Yes, it has been almost 10 years!

In 2010 I was doing a residency at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, and I went to all the different sites that used to do whaling. I wanted to find out why the Japanese were still eating and killing whales. I had a lot of research, facts, and narratives so I thought these texts should be presented in a book. I could’ve included it in the exhibition but it places a big burden on the audience when they’re negotiating the exhibition. I didn’t know why but I just thought I needed to make a book, so I started to compile it myself. It just felt like a reasonable and meaningful medium for this body of work.

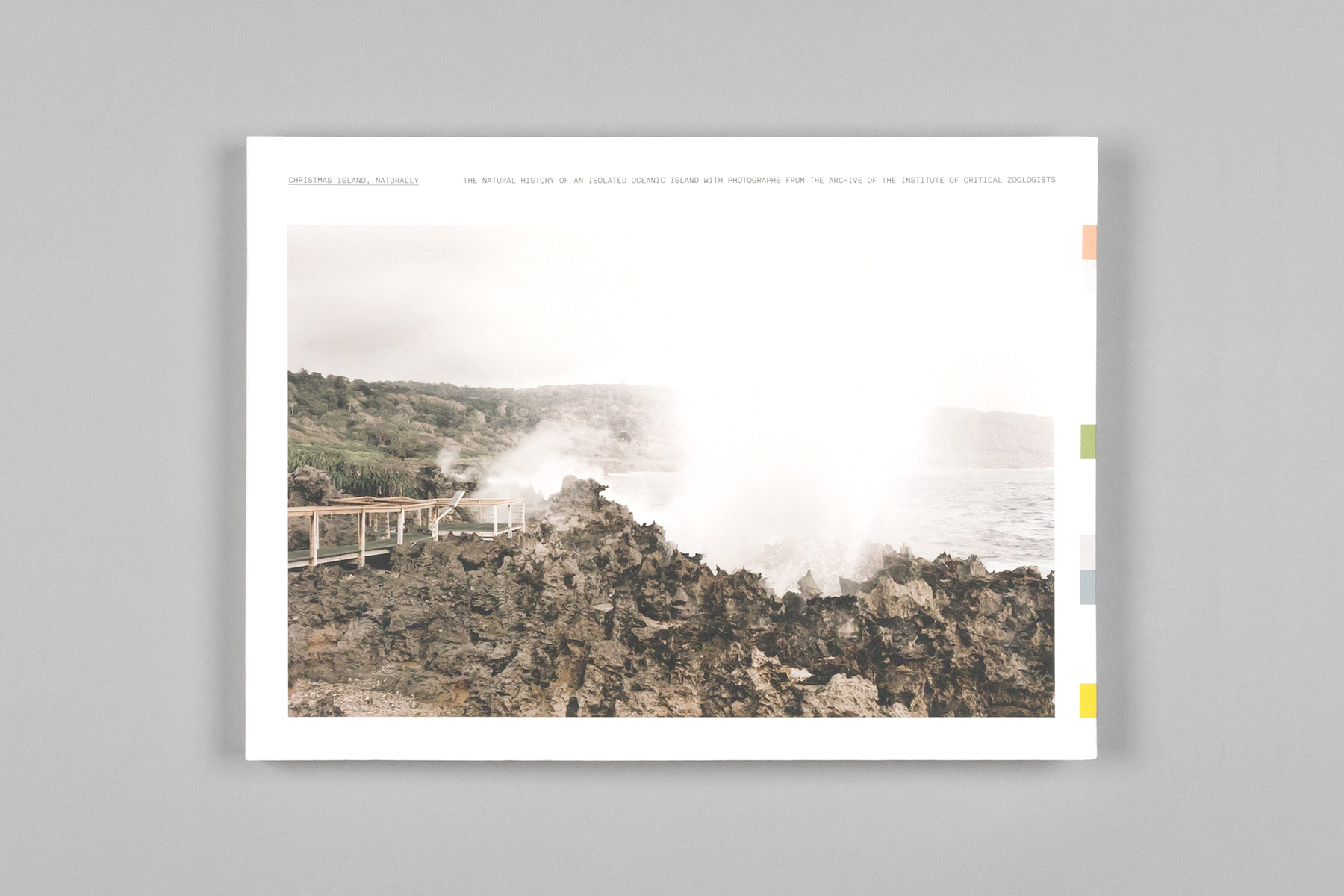

My second book was for my MA, and that was easy because I was a/the designer. I went to look at existing science journals and kind of replicated the design, the paper. I just tweaked everything into my own project. So actually a lot of my work is trying to mimic different forms — even the title for my book Christmas Island, Naturally is taken from an existing book.

Christmas

Island, Naturally, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: H55

Christmas

Island, Naturally, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: H55

SGABF: How was the progression from making zines to art books?

RZ: I started with zines when I was a student because that was all I could afford. The zine is much more economical because they go longer and further than exhibitions. More people get to see the work — which is also why I went on to make books. I started working with other designers as I became more aware of the need to be sensitive to the paper, the layout and the printing. As an artist, I’m already exploring ways of working within a space, how my artworks should behave, the framing and printing of the photographs, things like that. There are a lot of technical things I’m already trying to master. When it comes to the book, however, it’s a whole different ball game from an exhibition and there are designers who are dedicated to these experiences. It’s something I cannot achieve alone.

As I took on bigger exhibitions, I at least got paid so I started putting most of my earnings from art-making back into my work. I used the money to buy archives, old photographs and printed my books with them. Book-making is not a profitable thing, it’s not going to give me a 200% profit immediately; it’s a slow burn. But I’m very happy to see parts of my practice exist as books. My images are about ironic stories of human and nature that fall out of the mainstream narrative, not typical ones that are celebratory. It’s why I self-publish books; they are an expression of my art. No publisher would take on my books because it just wouldn’t sell.

Photo Credit: SGABF

SGABF: The Book and the Exhibition are both very different methods of presenting a body of work, both of which you are familiar with. How are the considerations similar or different from when you set up a show and when you make a book?

RZ: I think of my work in the form of a book, first and foremost. The exhibition is the last thing I think about because it’s abstract. The narrative is very important to me so the book provides a full sequence of everything I need to express in the project. Hopefully after I publish the book I have two to three months to reflect on the work because when you’re fresh out of a project, you cannot think very clearly.

From the book, I can see which parts I can extract and form footnotes that are crucial for the exhibition. There was a period when I tried to not have any text at all in the exhibition, but I realised it’s extremely tough because people are always looking for meanings. In the book I can be very precise and to the point but you don’t realise it’s actually fictional, so I’m just helping you understand as much as I want you to.

In an exhibition, I’m often more abstract with the text and work. The text doesn’t need to function literally as a caption. I try to give an abstract point of what the work could be about. People can make generalisations about your work with hints of facts from elsewhere. The text doesn’t need to actually be talking about the work you’re looking at.

My works are photographs that come with captions that are very important for the work. It’s not just a singular work, it’s work that comes in a series. I look for narratives and I use images to illustrate or capture these narratives. I use text to add another dimension to the images so when I sequence the images out, there’s a beginning, a middle and an end. All this can be controlled very effectively with a book. What I like about a book is that it’s always a one-on-one experience. You hold it in your hands, you open up, you look at the front, you browse — there’s a sequence in place, so my narrative is tightly in control with my audience. And I like that. I like to have that sequence with my audience. It’s also a lot more tactile. The papers, the printing, and the layout can kind of guide the viewer through the work differently.

With the exhibition — and with the audience plonked into a space — you are at the mercy of how the audience wants to negotiate with your work. It’s very hard to control a sequence, for example. To a certain extent, you can, but not as well as a book can.

SGABF: Do you feel that one has aided or hindered the other? Do you consider them separately?

RZ: The book has helped me to consolidate all the information that I have into a format that is logical. Most times my ideas come off very abstract until I speak to the designer, who has to understand the work. The design process is very important because through it, I get a better sense of what my work is or can be about.

A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World, Robert Zhao. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Artist

These days, my works take longer to produce because they are more research-intensive. I begin working on the book first before thinking about how the actual artwork will look. Book- and exhibition-making very much go hand in hand for me. It helps me as an artist to do the work at this point in time.

SGABF: You mentioned your work deals with a lot of fiction but the formats and mediums in which you work are very documentative and final. Nobody really questions the legitimacy of photography, for example. Does it affect how you work?

RZ: It’s very funny because what kind of art isn’t fictional? If I were a painter or a sculptor, people wouldn't always describe my work as a work of fiction. But because I’m a photographer and I make books, suddenly it tests the barriers of truth. Like a novel is fictional but at the same time so real, so you’re suspended in the state of wondering what’s real and what’s not; you’re negotiating between this boundary of world-making, fiction and truth.

A lot of facts that I uncover which are exciting for me are actually very boring for others. What I’m trying to do is narrate stories and make it exciting for the audience rather than purely present information, which would end up becoming a documentation.

I like photography because it’s so powerful that we don’t realise it at all. We become very naïve when we’re presented with a photograph. For example, pictures in advertisements and newspapers actually have very little to do with the product or story that they’re trying to sell. But we have become so comfortable with it. These images don’t have to have connections, they don’t even have to be genuine! I mean, some of us are more critical now, but in a general sense we are still quite flippant when it comes to reading images.

Artwork: Robert Zhao

SGABF: I was recently talking to Song Nian [from THEBOOKSHOW] and it seems like in Singapore it’s more common for photographers and designers to make books, rather than visual artists. Why do you think that is so?

RZ: I don’t think it’s limited to Singapore. It is generally very hard to find artists making books that are not catalogues. It’s not second nature for visual artists to make books because it is already so demanding to think of an exhibition. Perhaps a book to them has a utilitarian function, like a catalogue or a leaflet for the show.

As for designers, they already have the skill

sets to work with the book format well. This language may not apply to artists.

I guess you need a good publisher to translate artworks into a book too, like

what Roma Publications does. They strive to create artists’ books that do not

function merely as a catalogue.

The book as a medium needs to be handled well. It is easy to find a designer who can make a nice book but difficult to find one who can make a book based on a deep understanding of your work. A pretty book is easy to make, but a book that can translate your practice and work — that’s very hard.